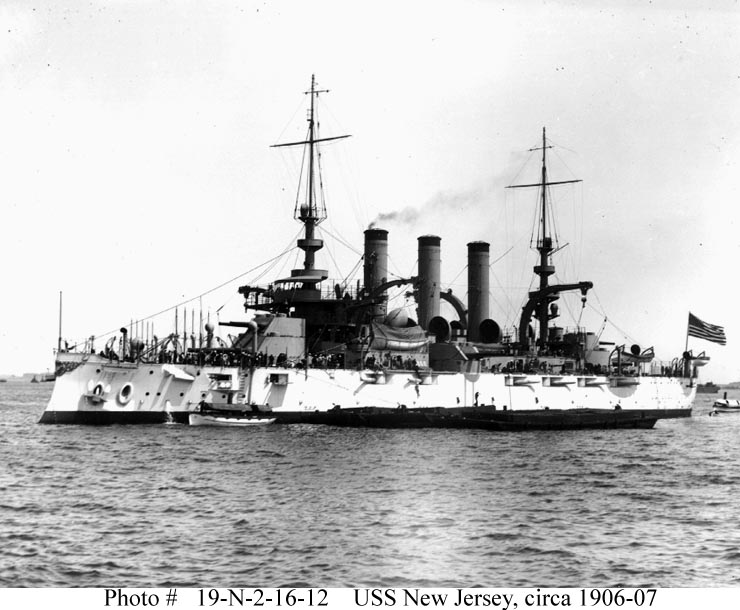

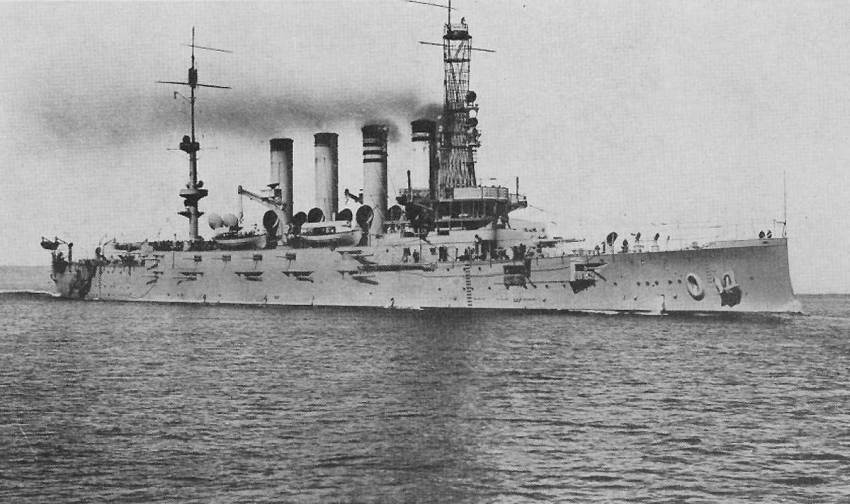

A few post ago, I had talked about the “Virginius affair” and “Great White Fleet”, The American Battle cruisers were a next generation evolution from the ships used in the great white fleet.

In fact, these battlecruisers had a central place in US naval thinking at the time. Their concept reflected a prevailing US Navy battle doctrine of ‘aggressive offensive action’. The same style of thinking was also applied to the designs of the first US ‘Treaty’ cruisers of the early 1920s. And the Lexingtons drew from specifically American tactical naval needs and thinking.

So how did they come about? The origins of US battlecruiser thinking can be traced to the naval ferment around the turn of the twentieth century when, like the British, French, Germans and Japanese – among others – US naval authorities were looking at the implications of a recent jump in the power of large warships. Heavy ships of the mid-late 1890s typically came in two flavors: battleships with a few heavy guns and a range of smaller weapons, backed with faster armored cruisers that carried a few medium guns and a usually similar array of smaller weapons.

Although a relative late-comer as a nineteenth century naval power, the United States was well up with the play. In 1902, Lieutenant Matthew Signor proposed a new type of battleship featuring six 13-inch guns and a battery of 10-inch. That was followed in 1903 with other proposals for a heavier armored cruiser – essentially a fast battleship, in terms of the standards of the day. The idea was further endorsed by the Naval War College Summer Conference of 1904. But cost was an issue. Into this was mixed warring theories about how naval battles might be fought. One result was tension between the conceptual ship proposals of the Naval War College and the more conservative designs prepared by the Bureau of Design and Repair. In a way it was predictable; the College could engage in blue-sky exercises, whereas the Bureau had the task of making warships reality, which included managing financial constraints and the political views that drove them.

By 1904-05, all-big-gun battleships were on drawing boards in Japan, the United States and Britain. However, the British, pushed by Fisher – as First Sea Lord – added turbine propulsion, completed their prototype, Dreadnought, ahead of the rest, and extended the concept to an all-big-gun cruiser design. These ships, the Invincibles , were initially classed as armored cruisers – the ‘battlecruiser’ designation was not formally applied by the British until 1911. Exactly what Fisher intended has been debated. Beating the latest armored cruisers was one motive, demanding a significant step-up in fire power but no increase in armor. There was also the concept of such ships being a fast scouting wing, able to deliver heavy punch to the enemy battle-fleet.

This thinking was shared across the Admiralty. However, Fisher also felt the heavy gun had won the gun-vs-armor race. Because ships were going to be size-limited, primarily for cost reasons, he felt it better to put displacement into speed and massive guns. Heavy armor was unnecessary. So too was anything other than minimal lighter weaponry. As Norman Friedman observes, by 1915 Fisher even opposed the heavier secondary guns required for anti-destroyer work.

The crucial point is that Fisher felt that all heavy construction should go into such faster ships. As early as 1902 he was arguing that there was little distinction between armored cruisers and battleships. ‘The Armored Cruiser…is a swift battleship in disguise’. And this is the point: to Fisher, the evolved armored cruiser became a replacement for the battleship. As First Sea Lord from late 1904 he put a good deal of effort into trying to persuade the rest of the Admiralty and the Cabinet to agree. In a way, he had a point. A fast ship with monster guns could keep a safe distance while dealing out massive blows. Fisher was not the first to come up with this idea: the Italian naval designer Benedetto Brin had explored it in the 1870s.

However, while this gained ground in Fisher’s circles – a group dubbed the ‘Fishpond’, the rest of the Admiralty disagreed. All an enemy had to do was build faster ships with larger and longer-ranged guns. And ships with speed superiority on paper might not be able to choose the range, thanks to weather or a raft of other factors such as loss of speed due to damage, or operational issues such as hull fouling, break-down or damage. For these reasons, Admiralty thinking leaned towards armor. The obvious answer was the fast battleship. However, although designs were mooted as early as 1906, they were unacceptably expensive to British governments trying to constrain military spending.

In the end, Fisher never convinced either the Admiralty or the British government to authorize battlecruisers in number. The original three were a windfall; the 1904-1905 building program called for one battleship and three armored cruisers on the basis that Britain was under-strength in the latter. Before any were laid down, Fisher’s Committee on Designs produced the Dreadnought and its cruiser homologue, the Invincible – and so Britain got one all big-gun battleship and three all big-gun armored cruisers, later dubbed battlecruisers. But aside from the 1908 ‘naval panic’ with the ‘contingency’ program approved in August 1909, only one battlecruiser was then usually authorized in each annual schedule, and the type was abandoned altogether in the 1912 program Battlecruisers were not re-visited until Fisher’s return to the Admiralty in 1914.

There was similar tension in the United States, where Britain’s Invincible design of 1905 seemed to meet aspects of Naval War College thinking about faster and more heavily armed cruisers. However, proposals from various American naval pressure groups, publications and the Naval War College during 1907-08 to build Invincible-class ships instead of new US armored cruisers were apparently an academic and profile-raising exercise. In fact, there was no chance even of indigenous US battlecruiser designs being authorized. More than one historical analysis argues that the US government had no clear naval policy at the time. More crucially, budgets were constrained. Congress typically authorized about half the number of battleships variously recommended by the General Board or the Bureau of Construction and Repair.

But in any case, while professional opinion within the US Navy was better-defined than in government – thanks in part to the Naval War College– thinking leaned towards heavily armed and armored battleships with moderate speed but good unrefuelled range. This was largely to meet US strategic commitments of the day, which focused on trans-Pacific interests. Such ships were intended to form a solid battle-line, to which the enemy would have to come if they were to defeat the United States at sea. This influenced the occasional foray into faster vessels. In 1910, the Chief Constructor of the Bureau of Construction and Repair, Rear-Admiral Washington L. Capps, organized six potential designs for fast all-big-gun armored cruisers, which had relatively modest speed by the British battlecruiser standards of that period – 25.5 knots – but with armor closer to contemporary US battleship scale. These were rejected by the General Board, which felt such ships were cruisers, and what the US Navy needed were more battleships.

Yet, within a few years, the US Navy was indeed pursuing the idea of battlecruisers – and, furthermore, battlecruisers with the massive fire-power, remarkable speed and thin armor that Fisher thought ideal. But this was for wholly US-developed motives, which diverged from Fisher’s reasoning. Proposals along the way included a surreal 1,250 foot long monster displacing over 60,000 tons. We shall pick up the story of how that happened, and how the latest mainstream British ideas about heavier armor then infused themselves into US battlecruiser thinking, in the next article.

The Virginius affair

Following the Civil War, the United States Navy had languished as funding was diverted to efforts aimed at rebuilding a wounded nation. Only a small handful of ships were kept to serve as a coastal defense force. Elsewhere, nations had observed the power of Ironclads during the Civil War and hastily began building fleets of iron plated warships. Somewhat Ironically, the United States had largely abandoned the development of the ironclad following the War. While they relied on leftovers from the Civil War, other nations began introducing more advanced ironclad models. This caused the United States to fall behind in quality as well as quantity. The United States needed a reminder that the Navy was an important component in strengthening the country. That reminder would come in the 1870s when the country found itself at odds with Spain during the Virginius affair.

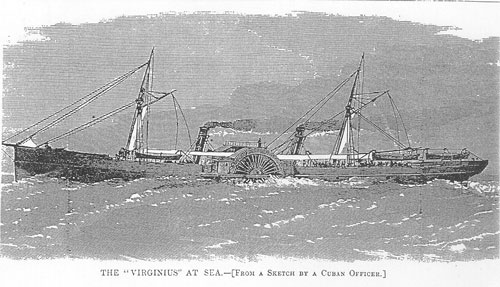

In 1868, war broke out in Cuba as landowners rebelled against Spain. Though the United States maintained stable relations with Spain, many in the country rose in support of the Cuban rebels. One such individual was John Patterson, an agent acting on behalf of the rebels. He desired to bring ammunition and supplies to the rebels. To accomplish this, he purchased a Confederate blockade runner named Virgin in 1870. Renaming the ship Virginius, she was used to transport supplies and men to Cuba in support of the rebellion. For three years, Virginius successfully delivered supplies to Cuba. Spain was aware of the ship and made many attempts to stop the ship.

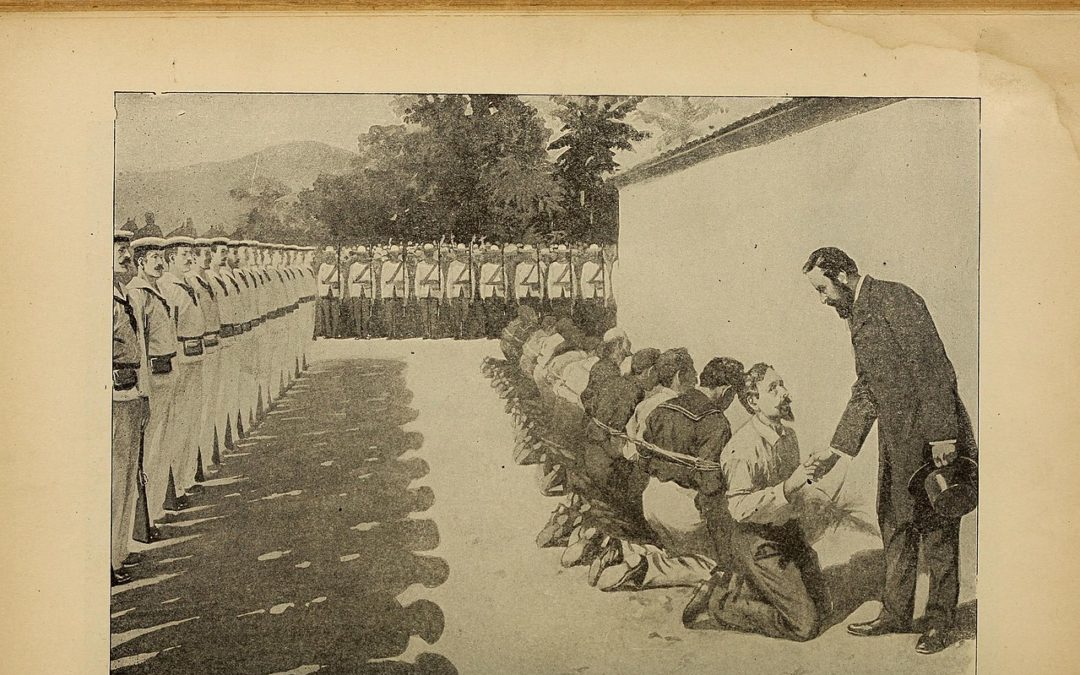

53 people were executed with several then being decapitated while the bodies were trampled under horses.

Fortunately, the British Government had become aware of what was happening and dispatched a warship to Cuba to investigate. The warship, HMS Niobe, arrived at the city of Santiago where the executions were taking place. The commander of the ship, Sir Lambton Loraine, immediately ordered the Spanish to cease the executions. Loraine even went so far as to threaten to bombard the city if his demands were not met. Spain relented and halted the executions, sparing the surviving crew of the Virginius.

The United States public, upon learning of the executions, immediately began calling for war against Spain. Luckily, the United States Government was able to diplomatically resolve the crisis. They secured reparations for the victims as well as the return of Virginius and her crew. This victory in diplomacy served to quell public anger and prevent the out brake of further hostility.

While the American public was demanding war, the United States Navy was no doubt dreading the prospect. At the time, a Spanish ironclad was in New York Harbor awaiting repairs. A more modern ironclad, the United States Navy had no warship in its inventory capable of engaging it. This led to the sickening realization that if war had broken out, the Spanish warship could have begun shelling New York City with impunity, the US Navy powerless to stop it. Had Spain sent its fleet to battle, the US Navy would be fighting an enemy with a larger number of more advanced ships. The US Navy was surpassed by Spain both in quality and quantity. To make matters worse, the few warships the United States had were incapable of fighting abroad

The available ironclads were originally designed for operation in coastal areas and on rivers. They could hardly make the 100 mile journey to Cuba much less sail to Spain from across the Atlantic.

While diplomacy was hailed as the driving force that settled the Virginius Affair, the US Government no doubt noted the effect that gunboat diplomacy had in preventing further executions. Spain had continued executing captives despite demands by the United States. The executions only stopped when a British warship arrived and issued a threat that Spanish authorities could not ignore. Military power had succeeded where diplomacy had not. The United States must have realized the weight of power a blue water fleet would provide on the negotiating table.

Luckily, the lessons of the Virginius Affair had not gone unnoticed. George M. Robeson, then serving as the Secretary of War, determined that the United States Navy must begin rebuilding itself into a more capable force. He immediately began calling for a new fleet of warships capable of matching those found in foreign navies. However, he faced stiff opposition from the United States Congress. Through clever tricks and outright deception, Robeson would eventually get his fleet. His efforts laid the groundwork that saw the United States Navy rise from a poorly equipped coastal defense force into a large, modern blue water navy able to project United States power abroad.

When the Virginius affair first broke out, a Spanish ironclad—the Arapiles—happened to be anchored in New York Harbor for repairs, leading to the uncomfortable realization on the part of the US Navy that it had no ship capable of defeating such a vessel. US Secretary of War George M. Robeson

believed a US naval resurgence was necessary. Congress hastily issued contracts for the construction of five new ironclads, and accelerated its existing repair program for several more.USS Puritan and the four Amphitrite-class monitors were subsequently built as a result of the Virginius war scare.All five vessels would later take part in the Spanish–American War of 1898.