Month: May 2021

https://youtu.be/-pejp5TU9Eo

These Guys also were one of the big reasons why Truman desegregated the Armed Forces after WWII. They were also the reason why Hawaii became a Democratic State after they came home. Where they faced the Republican backed powers that be. The Big Plantations, the Missionaries control of the land etc., etc. Grumpy

When the Chinese joined the fight, American troops would be surprised to find their opponents armed with a strange variety of small arms. Some of them were from the Eastern Bloc, others were recycled Japanese arms captured in China during World War II. There were even American-made rifles, submachine and machine guns provided to China via the Lend-Lease Act.

At the beginning of the Korean conflict, the American military was well-equipped for a modern war but rather unprepared for the nature of battle which would take place; an old-fashioned, gut-level infantry struggle across some of the harshest terrain ever fought over.

Eyes on the Sky

On Aug. 29, 1949, the Soviets shocked the world when they detonated their first atomic bomb, the RDS-1. The nuclear “balance of terror” that would define the Cold War had begun. Less than a year later, the Soviets debuted their world-leading MiG-15 jet fighter, and on Nov. 1, 1950, the first jet-versus-jet combat took place when a Soviet pilot named Khominich downed a U.S. Air Force F-80C.

Soviet pilots (called “Honchos” by the U.S.A.F.) covertly flew MiG-15s in North Korean or Communist Chinese air force colors throughout the Korean War. Consequently, America’s military attention was focused on advanced Soviet weapons technology. Soviet-made small arms were otherwise generally overlooked.

Eastern and Western Philosophies in Conflict

As I began to research this article, I sought to gather resources that provided details on Communist small arms from the beginning of the Korean War. I quickly learned such information is nearly non-existent.

U.S. Ordnance was very proud, and rightfully so, of the American arms that proved so crucial to Allied victory in World War II. Axis infantry weapons, particularly the later German designs, were carefully examined and assessed by American weapons experts. Across the board, German designs were judged to be inferior to U.S. weapons.

Certain German concepts, like the “General Purpose Machine Gun” that were the basis of the MG34 and MG42, were explored for later U.S. designs. Other concepts, particularly the MP44 Sturmgewehr “assault rifle” and its intermediate cartridge were not embraced by U.S. Ordnance initially. Work began on improving the M1 Garand, but the M14 rifle that would come to replace it did not enter service until 1958.

After World War II, the Soviets were busily working on small arms to leverage their M43 7.62×39 mm cartridge, which was developed from the German 7.92 mm “Kurz” round. Even so, the now-famous SKS-45 rifle and the AK-47 would not reach standard-issue status until well into the 1950s, and neither one would see service in the Korean War.

The Soviets would supply their Communist allies with the same weapons the Red Army had used so well during World War II. American military leaders overlooked the fact that 80 percent of all German combat casualties in World War II came on the Eastern Front. Those same weapons, considered crude by American standards, coupled with the basic infantry tactics of the Red Army were waiting for U.S. troops in Korea.

In the March 1951 issue of “Popular Science”, editor Perry Githens wrote a review of Communist small arms captured in Korea titled “How Good Are Russian Guns?” Githens writes:

“It is true that many of the Russian-made weapons I saw and handled at Aberdeen Proving Ground look, at first glance, like practice work in a school for lady welders. It is also true that they can kill you very dead at the effective ranges for weapons of their type.

How good are Russian guns? Just exactly good enough and no more. …For Russian weapons are a literal reflection of the harsh Asiatic philosophy that life is cheap. Where men are expendable, so are guns. And if guns are to be lost in the grinding of war we politely call “attrition,” it is better to lose cheap guns.”

I mentioned that pre-Korean War references on Soviet small arms were hard to find. To my knowledge, there was one American arms expert actively writing about Soviet guns in this era. His name was Roger Marsh, a gunsmith, gun writer and NRA member from Hudson, Ohio. In 1950, Marsh researched, wrote, illustrated and self-published “Weapons I: Overture to Aggression.”

Githens mentions Marsh’s soft-cover book in his article, calling the work “excellent” and “brief but meaty.” Those are accurate descriptions, and “Weapons I” also provides a valuable snapshot of what we knew (and should have shared with our troops) about Soviet-made small arms as the Korean War began. Along with the details he shares in his book, Marsh also provides some interesting editorial:

“Although there has been little reported on the subject, it is rumored that the North Koreans have held classes for their men in the use of U.S. weapons. Its logical: Communist activists are expected to know the use of their own weapons and those of their enemies, and the North Koreans found added incentive in the fact that they expected to have a quick brawl with U.S.-armed South Korea.

I wonder if U.S. forces are getting comparable instruction in the use of Soviet and other foreign equipment? The Germans were publishing extensive information on Soviet weapons in 1941-1943, and it is 1950 now. In 1943, in the Armorers Section, ORTC (Aberdeen Proving Ground), I set up, wrote the lessons plan for and the instructional materials for, and repaired or rebuilt the material for and trained other instructors for a Foreign Material course. Maybe it saved some American lives…we did the best we could. The services have had a seven-year start anyway. I hope they have done something with it.”

Opponents Old and New

When the Chinese joined the fight in Korea, American troops would find their opponents armed with wide variety of small arms. Some were made in the Soviet Union, others were repurposed Japanese arms captured in China during World War II and finally, there were American-made rifles, SMGs and machine guns provided to Nationalist China via Lend-Lease and then absorbed into the Chinese Communist Army after China’s civil war.

The 1953 U.S. Army Military Intelligence Guidebook “Material in the Hands of or Possibly Available to the Communist Forces in the Far East” lists the following Japanese small arms potentially in the hands of North Korean or Chinese Communist troops:

- Type 14 pistol (8 mm Nambu)

- Type 94 pistol (8 mm Nambu)

- Type 38 rifle (6.5×50 mm)

- Type 99 rifle (7.7×58 mm)

- Type 96 Light Machine Gun (6.5×50 mm)

- Type 99 Light Machine Gun (7.7×58 mm)

- Type 92 Heavy Machine Gun (7.7×58 mm)

These weapons, along with the Type 89 50 mm Grenade Discharger, commonly called the “Knee Mortar”, made up the bulk of Japan’s World War II infantry weapons, all of which were captured in large numbers by the Chinese and remained in their service until the mid-1950s.

Red Impressions

Several Soviet weapons made a significant impression on U.S. troops in Korea. During World War II, the Red Army was often short of rifles, and the Soviet remedy was to replace long arms with considerably less-expensive submachine guns, quite often at a ratio of three-to-one. Primary among these submachine guns was the PPSh-41 (7.62×25 mm Tokarev), and more than six million of them had been produced by the end of World War II.

Entire units were equipped with the PPSh-41, and with it, the Soviets introduced the idea of tremendous infantry firepower, albeit at short range, to combat on the Eastern Front. They shared the PPSh-41 with their satellite states, and licensed copies were created in North Korea (the Type 49) and China (the Type 50).

The PPSh-41 and its clones feature a high cyclic rate, 900 to 1,000 rounds-per-minute. Equipped with either a 71-round drum (the Russian and North Korean models accept the drum) or a 35-round box magazine (the Chinese version only accepts the box magazine), the PPSh spits out a lot of lead in a hurry. When Communist troops closed the range in Korea, the PPSh submachine guns gave them an advantage in firepower. G.I.s called it the “burp gun”, and some U.S. infantry commanders considered the PPSh-41 to be the best short-range infantry weapon of the war.

No Communist weapon brought forth as much curiosity from American troops as the Soviet PTRD-41 and PTRS-41 anti-tank rifles, chambered in 14.5×114 mm. These massive rifles, 79.5” for the PTRD and 83” for the PTRS, overlooked or considered obsolete in the West for a decade, made a big impression on American troops in Korea. What the G.I.s called “Buffalo Rifles” had been the Red Army’s prime man-portable anti-tank weapon of World War II.

The Western Allies had given up on anti-tank rifles by the end of 1941, but the Soviets had effectively used their 14.5 mm AT rifles until the end of the war. While other nations assumed that for an anti-tank weapon to be worthwhile it must be able to penetrate the enemy tank’s armor where it is the thickest, the Soviets employed their anti-tank rifles to target sensitive points like running gear, vision ports, engine compartments and even cannon barrels.

AT rifles were deployed in depth, with multiple weapons firing at a vehicle from several angles. Once disabled, the tank was vulnerable to roving Soviet tank-hunter teams. As World War II progressed, the Red Army found useful secondary applications for their PTRD and PTRS rifles, most notably in sniping at hardened enemy machine gun and artillery positions. The big rifles, along with their doctrine for use, were provided to the North Korean and Chinese Communist armies.

Interviews with North Korean P.O.W.s revealed that they were well aware that their anti-tank rifles could not penetrate the frontal armor of U.N. tanks, and thus, Communist AT rifle teams targeted lightly armored vehicles and motor transports, along with machine-gun bunkers and artillery positions. The enemy “Buffalo Rifles” drew attention for their potential as big-bore sniper rifles.

American sniping expert, Lt. Col. William S. Brophy took a captured PTRD-41 AT rifle and reworked the weapon with a .50-caliber machine gun barrel, adding a Unertl scope and the small comfort of a butt pad. Using his early conversion, Brophy successfully engaged enemy targets at more than 1,000 yds. This basic modification became one of the forerunners of the modern .50-caliber sniper rifles we know today.

Roger Marsh describes the Russian-made AT rifles in his book “Weapons I”:

“No US weapon or class of weapons corresponds exactly to the PTRD/PTRS class. The closest approximation is the M2 Caliber .50 Heavy-Barrel Browning machine gun.

Unquestionably, as far as general effectiveness is concerned, the high rate of fire of the M2 makes up for the differences in ammunition and weight, but is it impossible that a weapon of the PTRD/PTRS class might be of use in U.S. service? The PTRD weapon is surprisingly light for a weapon which can punch a hole in 30 mm thick armor at 100 meters. Perhaps an American version of the 33-lbs. PTRD type would be useful where the M2 could not readily be carried, but where a weapon effective against medium armor and motor transport might be useful, as, for example, in a behind-enemy-lines raid on supply facilities and motor pools.”

The Soviets also provided the Mosin-Nagant M1891/30 rifle (7.62×54 mm R) to their Communist allies. Chinese and North Korean snipers used these weapons, either in their standard configuration or equipped with a 3.5X PU scope. As the Korean War became a stalemate during the final two years of the conflict, snipers on both sides of the lines took their bitter toll of unwary opponents.

Soviet-made machine guns made a strong impression on the Korean battlefield as well. The venerable Maxim M1910 water-cooled machine gun was already a veteran of two world wars by 1950. Many of these were attached to the wheeled Sokolov mount, a low-profile configuration often fitted with a light armored gun shield. World War II models of the Maxim gun had a radiator cap added to the top of the water jacket, allowing snow to be easily added to keep the barrel cool.

G.I.s came to respect the light DP-27 “Degtyaryov” machine gun (7.62×54 mm R), which featured an odd 47-round pan-shaped magazine. Somewhat comparable to the BAR, the DP-27 weighed in at about 25 lbs. loaded and provided the base of fire for better units of the Chinese Army. Communist forces also used the Soviet SG-43 medium machine gun (7.62×54 mm R), and this more modern Soviet machine gun was new to American troops, apparently. Roger Marsh makes mention of this in his “Weapons 2” (1952):

“The SG-43 “Goryunov”: The Goryunov is now almost 10 years old. It was used in World War II—extensively. And yet, when the Korean Incident began, the Goryunov came as a complete and terrible surprise, according to the newspapers. One wonders how such things can happen. We can’t afford many more “surprises”.

Acceptable War Trophies

It is interesting to note that the 1953 US Army Military Intelligence Guidebook “Material in the Hands of or Possibly Available to the Communist Forces in the Far East” provides a list of “Permissible War Trophies” in the Far Eastern Command. All ordnance items of Japanese, German, Chinese, Polish, Czech, Rumanian, Albanian, Hungarian and Bulgarian manufacture were considered acceptable trophies, provided they were manufactured prior to the end of World War II.

No Russian-made items were deemed acceptable war trophies, and U.S. troops were instructed to turn over any captured Soviet equipment to their superior officers. The Cold War was already hot, and U.S. Ordnance intelligence had plenty of catching up to do.

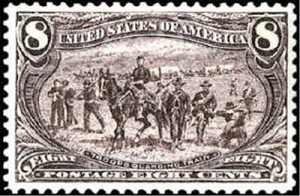

Frontier Infantry 1866-91

Posted on: February 2nd, 2014 by Will Rodriguez

Protecting the wagon train by Frederic Remington

Essay by Yankee Papa (all rights reserved)

In June of 1866 700 men of the 18th Infantry Regiment were marching out of Fort Laramie heading up the new “Bozeman Trail…” This would save hundreds of miles from the old route to the mines in Montana.

The weather was splendid and the troops were marching towards some of the most beautiful country in North America…at least in June. They were also marching into the hunting grounds of the Lakota, the Northern Cheyenne and the Arapaho.

That wasn’t supposed to be a problem. Peace Commissioners were meeting with the chiefs at Fort Laramie as they marched past. Unfortunately some of the chiefs were deeply opposed and nothing had been agreed upon when the troops showed up to build three forts in their territory. A couple of the most fierce, including Red Cloud called foul and rode off pledging war.

As they were too often wont to do, the commissioners decided to ignore the hostile or no show chiefs and just get the signatures of the ones present… even though it might not be their territory at issue. More than one war started this way.

But the word from the brass was that there would not be war… just some hotheaded chiefs… maybe some livestock raids on the posts. The high brass did not understand that as many as 4000 warriors might wish to dispute the matter with them.

The 18th had a proud record in the Civil War, but most of those lads had mustered out. Officers (who often had held higher rank during the war) and NCOs had seen combat… but not most of the common soldiers.

But… the brass indicated that there would be no major fighting. So many raw recruits and almost no training… just what little their NCOs could give them on their way. Drill and musketry not even scheduled until into the next year after the forts built.

The 18th was something new… it was not just made up largely of post-war men… but was among the first of the new blood on the frontier.

The remnants of the old marched past them as they neared Fort Laramie. The last of the “Galvanized Yankees”, former Confederates who volunteered to join the Union infantry to get out of the prison camps. Promised that they would fight Indians on the frontier, not their kin in the South.

(An interesting book by the way Grumpy)

(An interesting book by the way Grumpy)

Many were signed up for three years, and that meant that many were not discharged upon the end of the war. The last of the six regiments marched past the 18th on their way home to be discharged.

The soldiers of the 18th found that interesting, but were more concerned with their boots. Loss of weapons…illness and wounds… and bad feet could cripple an infantry unit.

Unless you paid a private boot maker, you bought “off the shelf…” In 1818 “lasts” were developed to enable production of specific left and right shoes… but this only came into common usage in the late 1850s… and with some minor exceptions, infantry in the Civil War and for some years thereafter (until Civil War stocks used up) had shoes with no left foot-right foot differentiation.

Prior to the march most NCOs would have shown the recruits how to fully soak the “boots” (up to the ankle and 4 sets of eyelets) and then let them dry on their feet before attempting to cover any distance in them. Easier to break in the boots than the feet.

Just as well that no fighting was expected…Colonel Carrington… well, everybody liked him, but he had never been in battle. Commissioned a Colonel from a law practice at the start of the war and handed the 18th Regiment… he was placed on “detached duty” for the entire war… staff duty in Washington.

If some of the officers thought that there might be a fight, they could not be happy at the Regiment’s strength… A new Civil War regiment contained 1000 men… the 18th only had 700… and of those all but 400 would be going to two forts… one at either end of the trail.

Actually they were lucky. A decade later and infantry companies on the frontier would not be at 70 like the 18th instead of the Civil War standard of 100… but down to a normal of 37.

And of course the rifles. The Ordnance Department had plenty of breech loading rifles in storage after the war… but chose to let the 18th head into the Powder River country with muzzle loading rifles (see https://gruntsandco.com/u-s-ordnance-rogue-fiefdom/ ) But then again, there was not supposed to be any fighting.

Only real Indian fighter around here, the Colonel’s guide… Jim Bridger. Even the recruits had heard stories about this old mountain man.

Bridger had his own assessment of what was going on. He thought that Red Cloud and some others would do more than just “steal some livestock…” A lot of horses, mules, and cattle that would have to be grazed outside the fort… Firewood to be cut some miles from the fort…something that required peace…

And then there were the women and children that the brass encouraged the Regiment to take with them. Total including workers of 400 civilians. Most would be at the fort in the middle of the trail… right in the heart of the Powder River hunting grounds. Colonel Carrington listened to Bridger… but the high brass assured Carrington that there would be no major hostilities…

[…The 18th had detachments build forts at both ends of the trail and built Fort Phil Kearny in the middle. Livestock indeed stolen and soldiers and woodcutters killed. On December 21, 1866, a Captain Fetterman… (had commanded the 18th at times during the war in higher brevet rank) put the seal on his disrespect to the Colonel and arrogantly disobeyed his orders.

Sent in relief of a wood chopping party, he instead rode after a party of Lakota to a ridge line. Ordered not to go past it, he did… with a mixed force of Infantry and Cavalry… 80 men. Just the number that he had boasted about… “With 80 men I can run roughshod over the whole Sioux nation.” Instead the Cavalry bolted to the front leaving the infantry panting behind… then more than 1000 Sioux rose up and caught them all in the open. It was over in a couple of minutes…

There would be other fights in the area, but the high brass in Washington decided what they should have in the first place… the soldiers could not guard the trail… only their own forts. Besides, Infantry needed to guard the trans-continental railroad that was being built. A treaty was signed… the troops pulled out by 1868 and the Sioux burned the forts behind them. It was the last war that Indians would win in North America…]

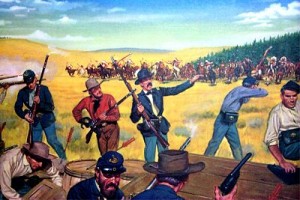

“Good Marksmanship and Guts” DA Poster 21-45

Near Fort Phil Kearney, Wyoming, 2 August 1867. The Wagon Box Fight is one of the great traditions of the Infantry in the West. A small force of 30 men on the 9th Infantry led by Brevet Major James Powell was suddenly attacked in the early morning hours by some 2,000 Sioux Indians. Choosing to stand and fight, these soldiers hastily erected a barricade of wagon boxes, and during the entire morning stood off charge after charge. The Sioux finally withdrew, leaving behind several hundred killed and wounded. The defending force suffered only three casualties. By their coolness, firmness and confidence these infantrymen showed what a few determined men can accomplish with good marksmanship and guts.

These days you mention the Old West and the Indian Fighting Army and people immediately picture Cavalry. Usually John Ford Cavalry. West had wide open spaces and the Indians had horses… so troops had to have horses… right? Oh, maybe some Infantry to guard the forts, but otherwise…

History tells a far different tale. There were never enough Cavalry… there never could be. The gigantic Union Army was mustered out and in the end, only 25,000 soldiers were left in the entire Army… many in the South enforcing Reconstruction.

A Cavalry regiment cost twice as much to raise as an Infantry regiment… and a lot more to keep running each year. And in spite of Hollywood… Infantry had a major role to play.

While mounted forces had played a role in every war from the Revolution on, there were no permanent regiments until the 1850s. Even then the mission a bit “fuzzy…”

Cavalry proper was supposed to fight almost exclusively on horseback. Dragoons were supposed to be able to fight some on horseback and some on foot. We had both, but at the start of the Civil War it was decided to call them all “Cavalry…”

Immediately after the Civil War a lot of regular and volunteer regiments were thrown into Kansas to put down Indian raids. Thousands of soldiers tracked endless miles and only killed two hostiles. Something else would have to be tried… and with a lot less soldiers… most of these were going to be demobilized.

Infantry would be needed for far more than to guard the forts. Wagon trains and supply trains would need escorts. While some Cavalry with the trains were handy… too many and they became a logistic nightmare.

American stock, unlike Indian ponies could not subsist on grass… Cavalry remounts needed oats and the like…a lot of them.

Even “all Cavalry” offensives had a limited range… In 1882 the assistant Quartermaster of the Army reported: “Unless cavalry operate in a country well supplied with forage, a large amount of wagon carriage must be furnished for forage and in such cases, cavalry is of little value except to guard its own train… and to do that in the presence of an enterprising enemy it will need the addition of infantry…”

Covering the Cavalry’s Withdrawl by Frederic Remington

Horses are, for all their size, relatively fragile. They can drop from a number of diseases and if worn out require an extended amount of time to recover. At the end of the day men are tougher than horses.

One officer who served in large expeditions in the Sioux and Nez Perce campaigns involving major units of Cavalry and Infantry, Sixth Infantry’s Col. William B. Hazen wrote “After the fourth day’s march of a mixed command, the horse does not march faster than does the foot soldier, and after the seventh day the foot soldier begins to out-march the horse, and from that time on the foot soldier has to end his march earlier and earlier each day to enable the cavalry to reach the camp the same day at all. Even with large grain allowances horses quickly deteriorated under extended exertion…”

In 1876 a 50 man Cavalry troop dismounted had less firepower on the line than an Infantry company of 37 men. Every fourth trooper had to take four horses to the rear and hold them there until the engagement was over. In addition the Cavalry was using shorter range carbines while the Infantry was using longer range (and more reliable) rifles.

The image of the “Cavalry riding to the rescue…” could not have been farther from the truth. In most cases, by the time that the Cavalry found out about a raid, the Indians could be fifty miles away… one hundred if they were Comanches.

Comanches might make a raid… then join up some miles off with couple of boys holding spare ponies… Alternate between them making distance. Cavalry, even an hour away would never catch up with them… just wear out their mounts. Cavalry had to dismount and walk their horses for a while every couple of hours to give them a breather. Meanwhile the Comanches kept swapping ponies.

One thing that cost the Cavalry was riding exhausted mounts into contact with Indians who were up for a fight… Reno almost lost his squadron when he had to retreat with blown horses (and exhausted, sleep-deprived troopers) at the Little Big Horn.

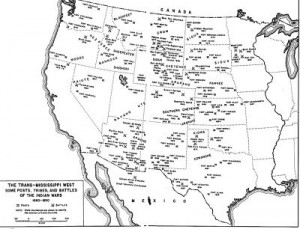

Map from “Winning the West The Army in the Indian Wars, 1865-1890” Army Historical Series

The only feasible military solution was to hit the hostiles in their villages… preferably in the winter when their mounts were scrawny. There were a number of problems with that strategy.

In the first place, during the Civil War a regiment of Colorado volunteers (enlisted for 100 days only) under a fanatic named Chivington had murdered many Southern Cheyennes at Sand Creek. Most of his men were bar sweepings and acted accordingly… rape, beheadings, “trophies” taken… slaves.

These Indians had followed the directive to camp by the nearest fort… but were ordered away by militia officers as a cynical prelude to slaughter. Other Indians were making the trouble… but these were closer… and both Chivington and the Governor of Colorado were looking for a cheap victory.

By the time that the people back East figured out what had happened, the regiment was paid off and the Army could do nothing. One regular officer who was going to testify was murdered in Denver.

So raids even into actual hostile Indian villages… though not as barbaric as Chivington’s would raise holy hell with people back East and their Congressmen.

And just what was a hostile village? Custer’s assault on Black Kettle’s village on the Washita, while not the insanity of Sand Creek was bad enough and raised troubling questions.

Black Kettle himself was an honorable chief who wanted peace. But war parties drifted in and out of his camp…some with hostages. He was not keen to have them rest up in his village… but tribal custom prevented him asking them to leave so long as they did not cause major trouble. He had no actual *authority*… as with most Plains chiefs, he led by his personality.

The Eastern media learned that Black Kettle had attempted to speak with the soldiers before the first shots were fired. He was shot and too many of the soldiers fired at anything that moved. It was a “victory” that would cost the Army in political support and in the unending enmity of both major branches of the Cheyenne people.

The biggest problem was identifying hostiles. Generally back when the Indian wars fought East of the Mississippi, a chief’s word would bind his tribe. On the Plains it was different.

A chief might sign a treaty with every intention of honoring it. But on the Plains both the war chiefs and the peace chiefs led by their personality and influence…not by compulsion.

Some members or clans of his tribe might decide to go their own way and raid. This caused reprisal raids (often by civilians) against the nearest members of that tribe regardless of any possible innocence. This of course led to those victims raiding the nearest whites… regardless of any possible innocence.

The reservation system was supposed to clear all this up. Those on the reservations would be labeled as “peaceful” and those off would be considered hostile.

But not all Plains Indians treaty bound to live on reservations. Some clans might…other might not. And some hostiles came to the reservations (mostly come winter) to rest up for new raids in the Spring. Some reservation occupants had permission to go off reservation on long hunting trips… Some were just that… others…

Shortly before the Little Big Horn campaign the government decided to reshuffle the deck. Indian tribes would no longer be treated as “sovereign nations” but as wards of the government. Certain tribes including the Sioux and Cheyenne were ordered (in winter) to report to a reservation or be considered hostile.

It is doubtful that many got the order…or would have considered moving in that weather… or even in the Spring. They saw no reason to give up their way of life.

The Army moved…and bungled the entire campaign…Custer’s blunders just one part of a bad set of events. But from this point the role of the Infantry would increase.

Like other troops on the frontier, the Infantry had some real problems. Their authorized strength too low… and usually could not meet that. Something like 37% of all troops on their first enlistment deserted each year.

Not just the low pay. Army preferred to pay in paper money at isolated posts. Counterfeiting so rampant for some years that most merchants would only take at a discount.

New troops got very little training. Most years no more than 16 rounds of ammunition per man for target practice. Often used on endless details having little to do with soldiering. If infantry present at a fort, they got most of the endless chores… most troopers work time centered around their mounts.

While officers preferred “Iowa farm boy” type recruits…they usually didn’t hang around. Many of the best soldiers were the Irish and Germans… at least those who made it into the NCO ranks.

Many people have heard of the two regiments of black soldiers in the Cavalry. But there were also two regiments of Buffalo Soldier Infantry on the plains. On average they were a better investment than many of the white recruits.

Lot of drunks and loafers and other types likely to get into trouble and/or desert joined the white regiments… But there was a surplus of good quality men wanting to join the black regiments.

Desertion was a very small problem. Training took longer because of their background (this happened in Rhodesia with the Rhodesian African Rifles as well), but once trained up, these men proved superb soldiers.

Most white officers outside the black units looked down on the regiments…prejudice… nothing more. At the end of the Civil War Custer had refused the rank of full Colonel with a black regiment and chose to be a Lt. Colonel of a white one. (Actual commander, Colonel Sturgis always on temporary duty in Washington until after Custer’s death.)

Whether in garrison, or even in the field, the Buffalo Soldiers often looked smarter than their white counterparts. Some of that was their desire, and that of their officers to look like proper soldiers. Initially, part was because by the time that the black post-war regiments formed, the Army was out of their stocks of poorly made Civil War uniforms (bad contractors) and only had the later quality stuff left.

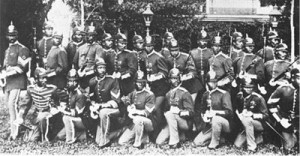

Company B of the 25th Infantry was stationed at Fort Snelling, Minnesota, from 1883-1888.

They pose here in their full dress uniforms. U.S. Army Signal Corps photo

After Custer’s famous luck ran out, the Army got orders to clean up the plains once and for all. The Infantry now would show what they could do.

The Infantry did whatever it took… The Fifth Infantry’s Colonel… Nelson Miles… put some of his troops on confiscated Indian ponies to help run the hostiles ragged and keep them from assembling in mass numbers.

But the real mission for the Infantry was a foot job… Hitting the Indian camps in the winter. The idea was not to win a big battle to the finish… Too often women (who often fought) and children caught up in the gun play and too many warriors would escape.

And a desperate fight for a village would often result in heavy casualties among the troops. At Big Hole later against the Nez Perce, troops from another Department would learn that the hard way.

The object was to cause the hostiles to flee… leaving their winter camps behind them… their shelter… massive food stores… and often most of their spare ponies. The best would be used and later sold… the rest shot.

The Indians would stagger into another village of the same or allied tribe… but they too could be hit by the “walks-a-heaps” tomorrow. One winter of the Infantry doing this broke the backs of the Sioux (many of whom fled to Canada…where only the Royal Navy prevented the U.S. Army from crossing after them…)and the Northern Cheyenne. The foot sloggers could hold up better in appalling weather than Cavalry remounts.

There were other campaigns on the plains… the Nez Perce battles that often involved Infantry… including their final one. Then in Northern California the Modocs in the lava beds where only the Infantry could operate. Others…

Against the Apache the Infantry had its work cut out for it. If Wyoming and Montana cold in the winter… the heat of the Southwest could be hell on earth. And the Apaches liked it just fine…

Other than the expedient of the Indian ponies, there were two primary ways that the Army could mount Infantry. European mounted infantry rode horses but always fought on foot and carried rifles… not carbines.

But it takes time to get Infantry used to the bone breaking gait of a Cavalry remount. Besides, especially in Apache country horses prone to dying even when cared for by specialists.

The answer was to mount the Infantry on mules. Mules can be stubborn…but once one accepts the rider, their easy walking gait far easier for a novice to handle. Add to that that other than camels (used for a time in the 1850s) they were the hardest critters to kill off in the desert. Unfortunately (from a Cavalryman’s standpoint) most mules will not charge into gunfire. Smarter than horses… and maybe their riders.

An elephant’s main strength is in pushing and pulling, but it can still handle a lot on its back. A properly packed Army mule could carry two thirds of the load (weight, not size) on its back that an elephant could.

One of the better Generals was a Colonel named George Crook who had worn stars in the Civil War and after dazzling victories in Idaho and Oregon was promoted to Brigadier General over a great many heads.

“Crook refined the science of organizing, equipping and operating mule trains … selection of mules civilian attendants preferred… proper design mounting and packing of pack saddles…” (Utley)

But the best partnership was Infantry on foot… with pack mules (no wagons that could not go into nasty country)and Apache scouts from the same tribe… day or two out in advance.

This partnership was put to the test in Mexico in the Geronimo campaign. After the Apaches surrendered, they said that this combination gave them the most trouble. They could always mount up and ride away from their hideouts… but American and Mexican Cavalry all over the place… sudden moves dangerous… Meanwhile the Infantry and mules would be maybe a day behind the scouts…as persistent as the scorching sun.

Grant’s troops in Virginia would not have recognized one of these companies. No bugles on the march…bayonets left in barracks. No glorious dark blue tunic over sky blue trousers.

Like Captain Henry Lawton’s company out of Fort Huachuca, they marched in white long underwear and campaign hats.

These companies marched without the drunks and the slackers. They had some of the roughest on the job training on the frontier…that produced hard-bitten professionals. They were a world away from the green 18th Infantry lads marching up the Bozeman Trail in 1866.

This period of the “Dark Ages” of the United States Army lasted from 1866-98. But these Infantry companies in Mexico would not have been out of place in many Twentieth Century campaigns… from the Philippines to Nicaragua…

US Postage Stamp of Remington’s “Protecting the Wagon Train”

-YP-

Suggested Reading

http://www.amazon.com/Crimsoned-Prairie-S-L-Marshall/dp/0684130890/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1390888130&sr=1-1&keywords=crimsoned+prairie

http://www.amazon.com/Frontiersmen-Blue-United-States-1848-1865/dp/0803295502/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1390887589&sr=1-1&keywords=frontiersmen+in+blue

http://www.amazon.com/Frontier-Regulars-United-States-1866-1891/dp/0803295510/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1390887935&sr=8-1&keywords=frontier+regulars+utley

http://www.amazon.com/Dose-Frontier-Soldiering-Corporal-1877-1882/dp/0803242328/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1390887799&sr=1-1&keywords=soldiering+american+southwest

[CORRECTION UPDATE: The above version of YP’s essay is an updated version. The editor (me) originally published an earlier and slightly shorter version. Apologies to all.]

Be Respectful, Candid and Pertinent. No Posers, No Trolls…

|

|

The Colt Trooper was billed as a heavy-duty no-nonsense swing-out cylinder revolver and it was popular across three decades. (All Photos: Guns.com)

First introduced in 1953, the Colt Trooper was a six-shot revolver that had a lot of style and remained in production for over 30 years.

Borrowing the company’s standard E-frame double-action revolver format from the Colt Officer’s Model, the Trooper was, when it was first introduced, something of an entry-level multi-purpose .38 Special. Complete with adjustable Accro-style rear sights and a “quick-draw” front ramp it was marketed towards police use, hence the name.

At introduction, the wheel gun was also produced in a similar-sized .22 LR with a 4-inch barrel that was sold as an economical “trainer” revolver. As with all E-frames, it had a hammer-mounted firing pin. At the time of its introduction, it was one of Colt’s least expensive medium-frame revolvers, costing about $71, while the Model 357 cost $75 and the Officer’s Model Match ran $79.50.

By the late 1950s, with the Colt .357 Model discontinued and the new premium Colt Python making headway with those who could spare the coin, the Trooper was likewise upgraded to a large I-frame format. With a frame-mounted firing pin, it was offered in .357/.38 with checkered walnut grips. In 1966, the price of the Trooper in .357 had risen to about $92, which was still a bargain as the new Python, with Colt’s Royal Blue finish, was $140 at the time. As such, it was the ideal companion for hunters or as a service weapon or for home protection.

This circa-1965 Colt Trooper is looking for a good home and is a good example of the I-framed 4-inch .357 Magnum variants offered at the time.

Meanwhile, this circa-1966 6-inch Trooper, also in .357 Mag, shows what the breed looked like when stretched out a bit

While the Python and the then-newly designed Diamondback had a high vent-rib full lug barrel, the Trooper kept its old-school thin barrel and distinctive ramped front sight. Well, for a while at least.

In 1969, the model was tweaked further with the introduction of the J-frame MK III standard, which had a coil mainspring and redesigned lock work to allow the guns to be more machine-fitted rather than hand-fitted. These guns had a very different profile from the earlier Troopers.

This Colt Trooper MK III in the Guns.com Vault dates to 1981 and has a 6-inch barrel. Like most Troopers observed in the wild, it is in .357

The MK III Trooper was offered in .357, .38 Special, .22 Magnum, and .22 LR with a choice of 4-, 6-, or 8-inch solid-rib barrels. For those looking for an even more low-frills version of the Trooper, Colt produced a variant with fixed sights but retained the same profile, and marketed it as the 35-ounce Lawman for about 15 years.

One of these things is not like the others! Another circa-1981 Colt Trooper MK III, this beautiful revolver is chambered in .22 LR and carries a “Colt Guard” electroless nickel-plated finish, which was only offered by Colt in the early 1980s before the company switched to stainless steel.

By 1983, the Trooper was in its last days and had been re-engineered to the MK V standard, which saw the gun with a different frame and firing mechanism that incorporated a longer mainspring. These changes were billed as producing a gun that had a lighter, faster double-action trigger pull with advantages for police competition or target shooters. Nonetheless, the final Trooper was the last of the line and only stuck around in Colt’s catalogs until 1986.

Although Colt had brought back several past revolvers in recent years, such as the Python and Cobra, the Trooper remains on the retired list.

However, since they don’t have the same point on the radar with gun collectors as they aren’t “snake guns,” the humble Trooper hasn’t seen the same wild spike in prices that has bitten other Colt wheel guns of the same vintage.

Colt Troopers were made from 1953 through 1986, and are beautiful old-school wheel guns that are often overlooked.

For other rare, interesting, and just downright unusual guns, head on over to our Collector’s Corner, where history is just a click away!