The Smith & Wesson “Victory Model“ was chambered in .38 Spl. and had a 4″ barrel as made under a World War II U.S. Navy contract. It is seen here being fired by Navy cadets.

In mid-1940, when it was becoming increasingly likely that the United States would be drawn into the war raging in Europe, the U.S. Navy, along with all branches of our armed forces, was evaluating the projected demand for arms. The standard handgun for the Navy at the time was the M1911A1 .45 ACP pistol. It became pretty obvious that the demand for these pistols would soon overwhelm the available supply, particularly since the Army and Marines would also be clamoring for handguns when war began.

The Navy adopted a policy of equipping its personnel with as many M1911A1 pistols as possible and obtaining a secondary source of handguns for “less critical requirements.” It was determined that the most suitable gun for this purpose was the Smith & Wesson Military & Police .38 Spl. revolver with a 4″ barrel. The M&P was Smith & Wesson’s “K-frame Military & Police” revolver which had proven to be popular in the civilian marketplace prior to the war.

This course of action was related in the Ordnance Dept. document “Project Supporting Paper; Miscellaneous Pistols and Revolvers”: “In addition to the M1917 revolvers … sizeable numbers of various other revolvers and pistols were procured by Ordnance. The United States Navy, unable to obtain the standardized M1911A1 Pistol, placed contracts directly with Smith & Wesson for the Caliber .38 Special, Military and Police Model Revolver.“

Although the U.S. Navy specified that the revolvers made under its contract be chambered for the .38 Spl. cartridge (technically, the .38 S&W Spl.), the British government also ordered large numbers of similar sixguns from Smith & Wesson chambered for another cartridge, the “.38-200”—which was essentially the .38 S&W cartridge with a 200-gr. lead bullet. This was later changed to a 175-gr. jacketed bullet.

The .38 S&W and .38 Spl. cartridges are sometimes confused, but they are two different chamberings and are not interchangeable; the .38 S&W is shorter and has a slightly larger diameter than the .38 Spl. As related in an Ordnance Dept. document: “From October 1941 to March 1945, Smith & Wesson produced the Caliber .38-200 Revolver for the British Army. This weapon was almost identical to the U.S. Navy’s Caliber .38 Special Revolver except for caliber and barrel length. The British revolver has a 5″ barrel, while the U.S. Navy used the 4-inch.”

While most of the S&W .38-200 revolvers did have 5″ barrels, some were made in 4″ and 6″ lengths as well. The 5″ barrel was made standard after April 10, 1942. Ordnance records indicate that a total of 590,305 of the .38-200 revolvers were manufactured by Smith & Wesson between October 1941 and March 1945, which was significantly more than the number of S&W .38 Spl. revolvers produced during the war.

Although the majority of S&W .38-200 revolvers were made under British contract and sent to Great Britain, some were also used by the U.S. military, chiefly for security purposes and for arming allies, such as resistance fighters. As discussed in Charles W. Pate’s excellent book, U.S. Handguns of World War II—The Secondary Pistols And Revolvers: “It is not a generally known fact, but the U.S. Army also used these arms (S&W .38-200 revolvers), though on a very limited basis.

There are a few documented cases of U.S. Army issue in the continental United States, primarily for guard purposes, and more substantial numbers were used in combat theaters. Several .38-200 serial numbers were found in OSS [Office of Strategic Services] hand receipt records of overseas units. But the revolver’s association with the OSS was primarily in that organization’s role in supplying resistance forces. Many thousands of .38-200 S&Ws were channeled through the OSS. In addition, it was the OSS that requested development of U.S. jacketed ammunition for the revolver.

“Clearly, the .38-200 S&W made a significant contribution to the war effort, especially with our allies. But with the end of the war drawing near and with the need for additional handguns lessening, the remaining .38-200 contracts were cancelled during the first quarter of 1945. Most components still in production were diverted to use in the .38 Special Victory Model, and surplus components in a finished state that were not interchangeable with the .38 Special, such as cylinders and barrels, were shipped to field service depots.

“After the war, thousands of the revolvers remained in the U.S. Army inventory as a regularly stocked item, but again, not for general U.S. issue. The primary use of these revolvers continued to be for arming foreign military and security personnel.”

Smith & Wesson U.S. Navy .38 Spl. Victory Model Revolver

While all of the .38 revolvers made by Smith & Wesson during World War II were dubbed “Victory Model,” the term as generally used today refers to the .38 Spl. 4″-barreled revolvers as made under U.S. Navy and U.S. Ordnance Dept. contracts. The Navy initially bypassed the standard procurement procedure of ordering its small arms under the auspices of the U.S. Army Ordnance Dept. and issued production contracts directly to Smith & Wesson. This course of action, however, soon resulted in problems, and Ordnance eventually got involved. As reported in the above-referenced “Project Supporting Paper; Miscellaneous Pistols and Revolvers”:

“The contracts at Smith & Wesson for Caliber .38 Special Revolvers were taken over by Ordnance, ASF (Army Service Force) in early 1942. Under Navy contracts, no inspector was stationed at the plant, and quality of revolvers suffered as a result. The Resident Inspector of Ordnance at Smith & Wesson worked under the handicap of having no drawings or gages with which to conduct a thorough inspection. The manufacturer had no complete set of drawings for the revolver so Ordnance inspection consisted of a visual and manual examination, function, proof and target firing. During the early production, as much as 30% of a day’s production was rejected for various defects.”

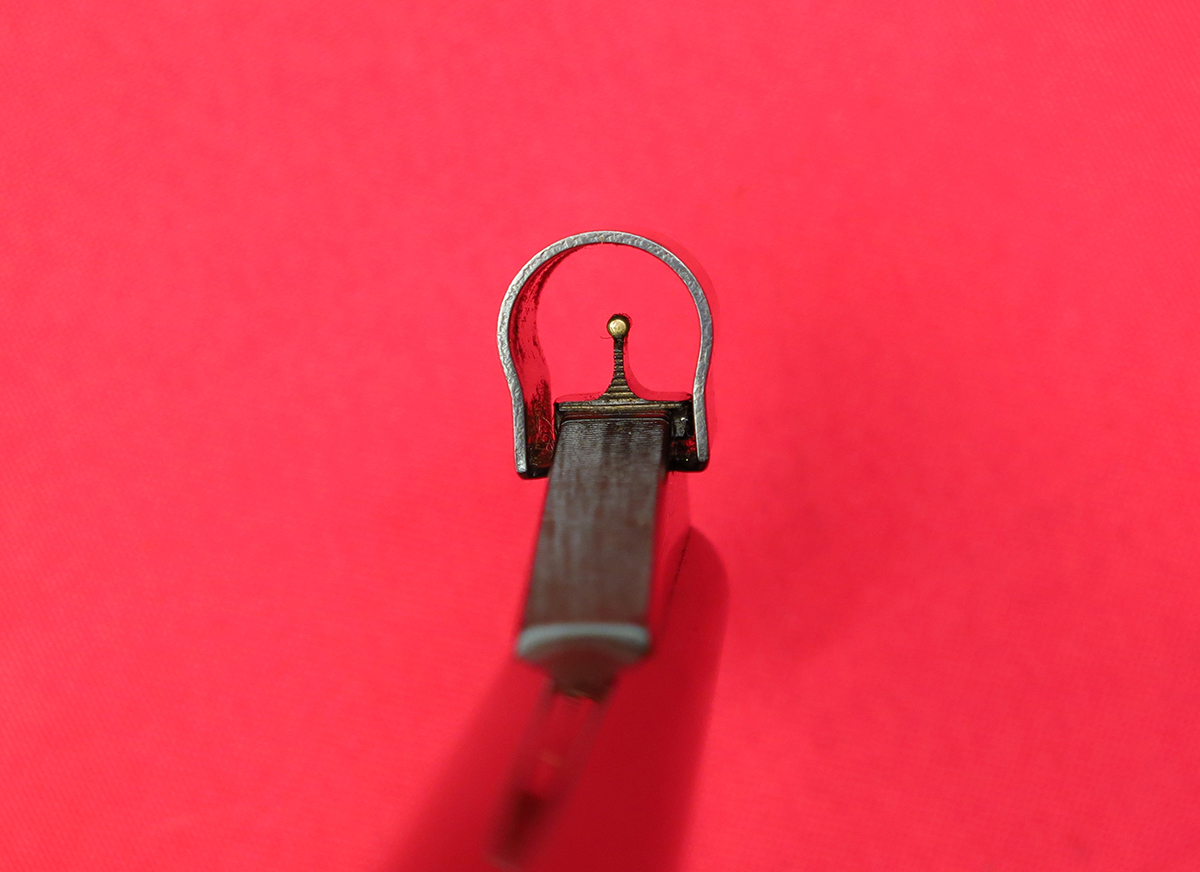

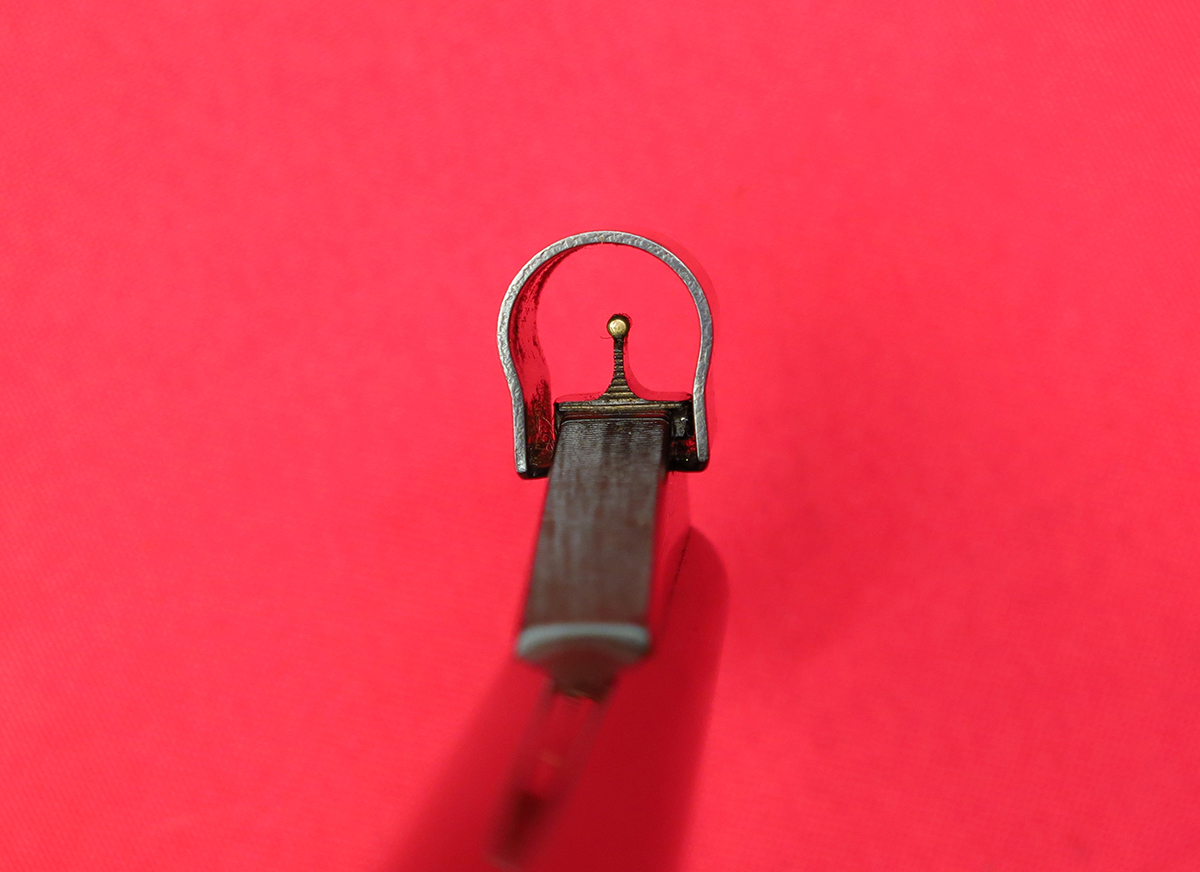

With the increased oversight by Ordnance, including more stringent inspection standards, the quality of the Smith & Wesson .38 revolvers continued to improve. The .38 Spl. revolvers built under Navy contract had 4″ barrels and the standard finish was Parkerizing. The serial number, having a “V” (Victory) prefix, was stamped on the butt. A lanyard ring was also attached to the butt. Some early production .38 Spl. Victory Model revolvers were not stamped with Navy markings at the factory.

In most cases, these guns were subsequently stamped “Property of U.S. Navy” on the left side of the frame. As production continued, the Navy markings were factory-applied to the topstrap above the cylinder. Approximately 65,000 Victory Model revolvers were purchased by the Navy directly from Smith & Wesson. After Army Ordnance took over procurement, the marking was changed to “U.S. Property G.H.D.” The “G.H.D.” marking signified U.S. Army Col. (later Brig. Gen.) Guy H. Drewry, head of the Springfield Ordnance District (SOD) in which Smith & Wesson was located.

Drewry’s initials will be found on other types of arms made in the SOD, including Winchester M1 Garand rifles, M1 carbines and military shotguns. It is sometimes believed that such initials represent the person who actually inspected the guns, but that was not the case. Rather, it indicates that the arms were inspected by Ordnance personnel operating under Col. Drewry’s authority.

The standard ammunition procured for issue with the .38 Spl. Victory Model revolvers was manufactured by the Remington Arms Co. The cartridges had 158-gr. steel-jacketed bullets, and the cases were head-stamped “REM UMC 38 SPL.” Standard commercial .38 Spl. ammunition with lead bullets could not be utilized in overseas combat zones due to provisions of the Hague Convention, thus the necessity for the steel-jacketed bullets. The cartridges were packed in green, commercial-style, 50-round cardboard cartons with lot numbers in the 5,000 range. There was also a limited quantity of .38 Spl. tracer cartridges produced during the war intended for signaling purposes.

Initially, the Navy restricted issuance of the M1911A1 .45 ACP pistols to overseas combat zones and used the .38-cal. revolvers for stateside Navy and Coast Guard personnel. Part of the reason for this policy was to mitigate the logistical problems inherent to having handguns chambered for two different cartridges in oversea theaters. Nonetheless, it didn’t take long for the impracticality of this policy to become apparent.

The lighter .38 revolver was actually preferred over the heavier .45 pistol by many Navy and Marine Corps aviators. By mid-1944, the Navy reversed its original policy and began to issue M1911A1 .45 pistols to some non-combatant personnel, such as guards aboard merchant vessels so that the .38 revolvers they would ordinarily be armed with could be available to flight crews.

The U.S. Navy and Marine Corps aviators generally carried their Victory Model .38 revolvers in a leather shoulder holster, often with web loops sewn onto the strap to hold extra cartridges. A leather hip holster was also made for these revolvers, but the shoulder holster was generally preferred by pilots due to space constraints in the cramped cockpits. The hip holsters were used more often by security personnel, but period photos show some flyers with their Victory Model revolvers in hip holsters.

While the U.S. Navy was the primary user of the S&W .38 Spl. Victory Model revolvers, Ordnance records indicate that some of the guns were also purchased by the U.S. Army and the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). As was the case with the S&W .38-200 revolvers previously discussed, the majority of these .38 Spl. revolvers were undoubtedly used for arming foreign security personnel and, in the case of the OSS, irregular military units.

However, some of the revolvers were utilized overseas by American combat troops, including U.S. Marines. As stated in R.G. Rosenquist’s Our Kind Of War, Illustrated Saga Of The U.S. Marine Raiders: “The M1911A1 .45 automatic pistol was the standard issue sidearm, but also plenty of .38 caliber Smith & Wesson ‘Victory Model’ revolvers saw action.” There are a number of contemporary accounts of .38-cal. revolvers being used in combat during World War II by American troops. Often the exact model is not mentioned, but, based on the numbers made and wide issuance, the odds are that most were the S&W .38 Spl. Victory Model.

For example, Marine Raider R.G. “Rudy” Rosenquist carried a .38 revolver, quite likely a S&W Victory model, and found it to be a literal life-saver during fierce fighting on Guam when he was bayoneted by a Japanese soldier: “[A]s the enemy soldier … stepped over him, Rudy reached up and grasped the man’s canteen strap and was yanked to his feet. The Japanese tore loose and rushed on. Now a second enemy soldier came running, and Rudy took a bayonet wound in the stomach. By this time, he had got out a .38 pistol, which he emptied into the man, who fell back upon the Marine at the machine gun … .”

As the S&W Victory Model .38 revolver was becoming a commonly issued sidearm, a problem arose that caused a temporary halt in the procurement of the guns. As discussed in an Ordnance Dept. document: “The death of a sailor, resulting from dropping a loaded Smith & Wesson, Caliber .38 Special Revolver prompted a test by the Navy Department to determine (the) effectiveness of the Smith & Wesson Hammer Block. Results of the test showed the Hammer Block to be unsatisfactory. This test was confirmed by a more carefully conducted test at Springfield Armory, authorized by Office, Chief of Ordnance.

Work was commenced immediately by Ordnance and Smith & Wesson to develop an improved Hammer Block capable of preventing discharge even if the revolver fell several feet, striking on the Hammer. This was desired because of the possibility of a seaman dropping a revolver from one deck of a ship to a lower deck. Deliveries of revolvers equipped with the present improved Hammer Block commenced in early 1945. The improved Hammer Blocks are vastly superior to the old type, samples tested having withstood 90-foot lbs. impact without firing.”

The death of the sailor due the S&W Victory Model’s flawed hammer block design resulted in the U.S. Navy requesting that Colt .38 revolvers be supplied for future requirements instead of the Smith & Wesson revolvers. However, it was reported that “ … improved quality and the quick development of a new hammer block convinced the Navy to stay with the S&W revolvers.”

Victory Model Revolvers With 2″ Barrels

While the vast majority of the S&W .38 Spl. Victory Model revolvers had 4″ barrels, there was also a little-known variant that was otherwise identical except for having a 2″ barrel. The revolvers were the subject of a May 10, 1944, letter from Stuart K. Barnes, vice president of Defense Supplies Corp., to Capt. F.M. Volberg, Small Arms Branch, Chief of Ordnance:

“[W]e have received advice from Smith & Wesson, Incorporated that they are prepared to produce a limited number of 2″ barrel .38 caliber Special revolvers without impairing their production schedule.

“The War Production Board, under the date May 8, 1944, has given approval for the production by Smith & Wesson of 500 .38 caliber Special 2″ barrel revolvers in order to supply essential non-military users. Therefore, it would be appreciated if permission would be granted for the production of 500 2″ barrel revolvers in lieu of 500 4″ barrel revolvers on subject contract at the earliest convenience and placed in the stock of Defense Supplies Corporation at Smith & Wesson Incorporated.

“These 500 revolvers would not be additional to the contract of the 35,000 4″ barrel .38 caliber revolvers, and would not constitute an increase in cost to Ordnance and this Corporation.”

According to factory records, the 500 Victory Model 2″-barrel revolvers were shipped to the Office of Strategic Services on Aug. 22, 1944. It has been reported that some were utilized by couriers, intelligence personnel and other individuals needing a handgun that was a bit more concealable than the standard 4″-barrel revolver. The only martial marking typically applied was a small “flaming bomb” insignia on the top of the frame.

It is easy to identify a genuine 2″-barrel Victory Model revolver from a 4″ revolver that subsequently had the barrel shortened. If a barrel was cut down from 4″ to 2″, a portion of the lettering on the barrel would be missing and a replacement front sight would be required, sure indication the gun had been modified. There was a well-made leather shoulder holster fabricated specifically for these 2″ Victory Model revolvers that had “US” embossed on the front. This would be suggestive that some were indeed used by U.S. military personnel. Original examples of these revolvers are quite uncommon today.

The S&W Victory Model revolver’s role in World War II is sometimes minimized or given little more than a cursory mention. Production of the Smith & Wesson .38 Spl. Victory Model revolver under U.S. government contracts (DSC, Navy and Ordnance) between 1941 and 1945 totalled the not-insignificant sum of 352,315 guns. While it wasn’t employed as extensively as was the M1911A1 pistol, it accompanied many U.S. Navy and Marine Corps aviators during the pivotal battles of the Pacific Theater. Its contributions to the war effort should not be overlooked.

Even though none were manufactured under government contract after 1945, the Victory Model revolver’s legacy extended well beyond World War II. It continued to be issued to some Navy and Marine Corps aircrews during the Korean and Vietnam wars and beyond. Uncle Sam certainly got his money’s worth from the Victory Model!

The anatomy of a gunstock on a Ruger 10/22 semi-automatic rifle with Fajen thumbhole silhouette stock. 1) butt, 2) forend, 3) comb, 4) heel, 5) toe, 6) grip, 7) thumbhole

Nathaniel “Texas Jack” Reed (March 23, 1862 – January 7, 1950)[1] was a 19th-century American outlaw responsible for many stagecoach, bank, and train robberies throughout the American Southwest during the 1880s and ’90s. He acted on his own and also led a bandit gang, operating particularly in the Rocky Mountains and Indian Territory.

Reed is claimed to have been the last survivor of the “47 most notorious outlaws” of Indian Territory.[2] He became an evangelist in his later years, and could often be seen on the streets of Tulsa preaching against the dangers of following a “life of crime”.[2][1] His memoirs were published in the 1930s, and are considered valuable collectors’ items (one copy was reportedly sold on the internet for $1,500 in 2007).[3] He claimed to have ridden with the Dalton gang, Bill Doolin, Henry Starr and other outlaws and bandits of the old west. He may have also helped Cherokee Bill, a fellow outlaw from the Indian Territory, in his escape from Fort Smith during the 1880s.[3]

As with many others of the era, Reed’s colorful stories of his almost 10-year career as an outlaw were probably exaggerated by later writers.[3] He claimed to have ridden briefly with the Daltons, and participated in their dual bank robberies in Coffeyville in 1892, as well as in the infamous 1893 gunfight at Ingalls. However, there is no corroborating evidence that he was involved in either of those events.[3]

Reed was born in Madison County, Arkansas. His father, Mason Henry Reed, was killed in action fighting for the Union Army during the American Civil War, probably at the Battle of Campbell’s Station on November 16, 1863.[2] His mother was Sarah Elizabeth Prater. Reed lived with a number of relatives, including his maternal grandparents, until 1883 when, at the age of 21, he moved to the American frontier.[4] He worked at various jobs in Idaho, Wyoming, Colorado, Texas until he reached Oklahoma, where he became a ranch hand for the Tarry outfit.[4]

During the summer of 1885, his foreman recruited him to rob a train at La Junta, Colorado.[2] In the course of the robbery, Reed entered the passenger car firing his pistol to keep the passengers under control.[4] He later received $6,000 for his part in the hold up.[2][4] Encouraged by this success, Reed gave up working as a cowboy and became an outlaw. During the next nine years he and his gang robbed trains, stagecoaches, banks and, on one occasion, captured a large shipment of bullion in California.[5]

During the early 1890s, when he was living near Muskogee, Oklahoma,[4] Reed learned that a gold shipment was leaving Dallas, Texas on November 13, 1894. He recruited Buz Luckey, William “Will” Smith and Tom Root, and selected Blackstone Switch at Wybark as the site for the robbery. The plan was for Reed to throw the switch as the train approached then, as it entered onto a sidetrack, the gang would use dynamite to enter the express car. Root, a full-blooded Cherokee known for his size and strength, would enter the express car, break open the strong boxes, and bring out the gold. Smith would hold a gun on the engineer and fireman while Luckey stayed with the horses.[4]

Despite their practice staged-robbery the previous day,[4] as the Katy No. 2 approached, Reed threw the switch too early. Engineer Joseph Hotchkiss stopped the train when he saw the signal light change,[4] far short of the siding. Reed and the others were forced to run towards the train yelling and shooting. Hotchkiss and the fireman alerted the messengers using the bell cord connected to the car and jumped off the train to hide in a small ravine nearby.[4]

The railroad company had anticipated the possibility of a robbery, and had moved the gold to another train, putting in its place several armed messengers to guard the express car including Bud Ledbetter, Paden Tolbert, Sid Johnson, Frank Jones.[4] When Reed and the others approached the express car, he called for the messengers to leave the car. When they refused, Reed and Root took cover behind some trees and began shooting into the car. The messengers returned fire, resulting in a gunfight that lasted for nearly an hour. Eventually one of Reed’s men was killed; Reed jumped onto the train and went through the passenger cars forcing passengers to put their valuables into a sack before he and his gang fled.[4]

As they rode away, Reed was shot by Bud Ledbetter; the pain from his wound grew so severe that his partners were forced to leave him behind for the night. He gave them some of his loot, and kept the rest of it in a sack to use as a pillow.[4] He lay on a blanket hiding under a rock ledge until he was found by an Indian woman, who nursed him back to health.[4][5]

The American Express Company offered a reward of $250 for the arrest and conviction of each member of the gang.[4] An extensive manhunt was conducted by U.S. Marshals George Crump and S. Morton Rutherford, and large groups of deputies were sent into the Indian Territory and Creek Nation. While burning the canebrakes in the Verdigris bottoms, one deputy found the burnt remains of Reed’s saddle and threatened to destroy the crops of local residents if they did not turn over Reed and his men.[4] This was considered a legal act, authorized by “The Hanging Judge” Isaac Parker himself, but no one came forward with information.[4] Reed was warned of the search and decided to leave the territory as soon as he was able. He arrived in Seneca, Missouri on December 9, where Bill Lawrence took care of him.[4]

Once fully recovered from his wounds Reed returned to Arkansas in February 1895, where he stayed with his brother in Madison County.[4] Having decided to retire from a life of crime, he wrote to Judge Isaac Parker, agreeing to testify against the man who planned the robbery in exchange for probation, although he did not participate in the proceedings.[5] Smith managed to disappear, but U.S. Marshal Newton LaForce was successful in tracking down Luckey and Root to the latter’s home in Broken Arrow, 15 miles south of Tulsa, Oklahoma. The two fugitives were subsequently killed in a gunfight with LaForce and his men on December 4, 1894.[4]

Despite Parker’s promise of immunity, Reed was convicted and sentenced to serve five years in prison.[5] However, he served less than one, as shortly before his own death Parker granted Reed his parole, in November 1896.[5] Reed subsequently carried his signed parole from Judge Parker around with him, along with a letter signed by Ledbetter acknowledging that Ledbetter had shot him.[5]

After his release Reed became an evangelist, preaching the rewards of living a respectable, law-abiding life.[2] He also toured the country with a series of Wild West shows.[5] His memoirs, The Life of Texas Jack, were published in 1936, and 35,000 copies of several published pamphlets and dime novels describing his life as an outlaw were sold before his death at home in Tulsa, Oklahoma, at the age of 87.[citation needed] He was buried in St. Paul, Arkansas.[3]