I have been extraordinarily busy in “the Real World”, I will post about it in a day to ‘splain what is going on….Nothing bad good news actually but it pulled me away from my blog.

I snagged this off “American Rifleman” It was fascinating read. I thought it was a different take on the Garand, I do know that the Germans had a different opinion on the Garand, the German Army Ordinance people didn’t like the Garand, they hated the sights and they considered the 8 round clip limiting. But we American considered the Rifle excellent for our needs and the rifle served us well. I know, I owned one until my untimely Kayak accident *Sniff, Sniff*.

The Japanese Type 4 semi-automatic is one of the most sought-after rifles by military collectors. Interest in it spans the spectrum from those who specialize in Japanese military arms to collectors of U.S. M1 Garand rifles to collectors of military rifles in general.

The Type 4 has been erroneously identified as the Type 5 in recent years. In the past, very little was known about development of the rifle. Model identification was established originally through information in a World War II U.S. Army Ordnance report where basic description, history and designation of the rifle as a Type 5 were presented.

In the same report, however, references were made to recovery of Type 4 semi-automatic rifle drawings at Yokosuka Naval Arsenal, which somewhat muddied the water. The Type 5/Type 4 argument has continued among collectors for some time. Examples marked Type 4 have shown up in recent years, and more information has become available that points to the proper nomenclature being Type 4. That said, the Type 4 is still recognized by collectors as a single variation when, in actuality, five variants of this very rare rifle have been identified.

Development of the Type 4 semi-automatic has its roots in an Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) semi-automatic development program initiated in mid-1931. The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) relied on army arsenals as a source of small arms for land-based personnel, so it sat on the sidelines and watched the IJA semi-automatic development program with special interest.

Initially, in the 1931 timeframe, Nambu Rifle Mfg. Co. was issued a development contract for a semi-automatic rifle intended for army use. Later, the program was expanded to include Tokyo Gas & Electric, Nippon Special Steel (NSS) and Tokyo Army Arsenal (Koishikawa). Nambu initiated development work with a gas-operated design featuring the army-specified five-round magazine. Tokyo Gas & Electric reverse engineered the Czech ZH-29 rifle, examples of which had been captured in Manchuria in 1931.

Nippon Special Steel presented a novel gas-operated toggle configuration, and Koishikawa provided a copy of the American-designed Pedersen rifle. In the case of the Pedersen design, J.D. Pedersen had taken his U.S. Ordnance Dept. trials rifle to Japan in the 1935 period seeking additional interest in the rifle. At the time Pedersen presented his rifle to Japanese army ordnance officers, they were not satisfied with progress on rifle development by private companies, and decided the army should develop a competitive rifle based on the Pedersen design. After all, they were being assured that the U.S. and Great Britain were in the process of adopting the configuration for the using services, so the design must be a winner.

The program, which now included the IJA itself as a contender in development of a satisfactory design, continued until 1937, at which time the program was curtailed. Politics were involved in the decision to stop the program, but of primary importance were the facts that military production was stretched to the limit with the expanding war in China, and it was readily apparent that Japan just did not have the production capacity to build the number of rifles required.

The semi-automatic program was reinstated in 1941. The using services were demanding more firepower, plus military use of semi-automatic rifles was becoming more and more common throughout the world. Since private industry in Japan was so focused on production for the war effort, the IJA set up a competition between two design groups within the army arsenal system, a unit at Kokura Arsenal and the small arms staff at the research center in Tokyo. The program continued until mid-1943 when it was halted because of similar issues faced previously, plus, very importantly, the failure to develop a satisfactory configuration for production.

The IJN was very disappointed in the IJA’s actions. The IJN needed more firepower for its land-based units, and the naval paratroop command desperately wanted a version of the semi-automatic rifle for its units. Japanese navy development of a semi-automatic rifle probably began in some form or other immediately after the army program ceased in mid-1943. Regardless, the program was included in a list of IJN ordnance action items for Fiscal Year 1944 (April 1943–March 1944) with three naval arsenals scheduled to participate—Yokosuka, Kure and Mazrui.

All three, however, were already working at full capacity, so arrangements were made for rifle development to be done on a spare-time basis at Yokosuka Naval Arsenal only. Development of the new rifle was carried out in the machine gun plant of Yokosuka Arsenal, specifically the third floor of the plant, as a spare-time activity in conjunction with production of 25 mm anti-aircraft cannons, Lewis machine guns and Vickers machine guns. With demand for machine gun production so high, priority could not under those circumstances be given to the semi-automatic-rifle program.

Even though a spare-time activity, the timeline for development of the new rifle remained very short. It has to be assumed that only one rifle was under consideration—the U.S. M1 Garand—because of the short timeline and no evidence of another design being evaluated. Captured samples of the M1 were warehoused at Yokosuka.

Stores of M1s had been found warehoused in Manila after occupation by the Japanese in 1942. Some were transported by the IJN back to Japan. The U.S. M1 represented a successful design in wide use, so IJN engineers decided to modify some of the captured rifles to 7.7×58 mm Japanese, the rimless cartridge standardized for use in the Type 99 bolt-action infantry rifle. In early 1944, 10 rifles were modified to 7.7×58 mm for testing. Functional testing and evaluation proved to be highly satisfactory. This success led to full development of the Garand copy.

First Variation Experimental Type 4 Rifle (Tool Room Example)

The overall brief development period leaves the impression that design and fabrication of the experimental Garand must have proceeded concurrently with modification of the 10 M1s in the early part of 1944. This was a success-oriented program with a lot of objectives to be met in a very short period of time.

Development from the toolroom example to the initiation of production took place during the first 10 months of 1944. Keep in mind that time must have been allowed during that period for tooling design and development, in addition to locating dedicated machinery. Very importantly, an initial effort had to be made to verify that Japanese ordnance had the capability of manufacturing all components of the rifle, some of which are very complex.

What I believe to be the toolroom rifle, or first experimental M1 copy, is functionally very similar to the M1 Garand; however, there are a few key differences. Attempts at simplification and improvement, those changes to the Garand include:

a.) 10-round integral magazine fed by standard five-round stripper clips instead of the M1’s eight-round en bloc clip.

b.) Ramp-type rear sight.

c.) Recoil lug integral with upper buttstock wrist tang instead of recoil absorption through upper stock ferrule.

d.) Lockup of the rifle through hooks attached to the trigger guard, which engage receiver lugs on back of magazine box instead of entering recesses in the receiver.

e.) Trigger housing retained to buttstock with screws instead of falling free during disassembly of the rifle.

f.) Simplified machining of receiver.

The specimen described has no serial number or markings, so it is thought to be the first and only example of its type that was fabricated. If more than one specimen were fabricated, typically, the rifles would be serialized, if only to prevent the mixing of hand-fitted parts.

Machining of the components of the single specimen known is crude where finish is not important to form, fit or function, and the rifle shows haste in fabrication. For example, the barrel, normally a long-lead item, is from a Type 99 rifle and has been modified to fit the new receiver. The Type 99 rear sight was obviously knocked off the barrel with a hammer during rebuild, leaving screw shanks still embedded in the barrel.

The rifle was originally obtained in an incomplete state. Only the barrel and receiver group was available. To complete the rifle to its original configuration, the buttstock and trigger housing group had to be configured and machined. This wasn’t very hard because features on the barrel and receiver group dictated the design of replacement components.

The original rifle probably failed at some point during testing, and the remaining parts were acquired by a veteran as a souvenir. The magazine well has significant powder residue and shows evidence of extensive firing. Most likely, this is the rifle described in U.S. Army Ordnance reports as being introduced to the paratroop command in March 1944.

Features on the toolroom example, plus subsequent test and production models, were required to meet paratroop requirements by configuration. The paratroop command desired a folding or break-down design, shortened in the stored state for transport in a soldier’s pack or leg bag. The U.S. M1 rifle breaks down into multiple segments, one of which is the trigger housing assembly.

The Japanese version, as designed, breaks down into two segments, the difference being the trigger housing assembly is retained to the buttstock group through the use of screws, plus the upper stock ferrule is retained in place via three small nails. The Japanese Type 2 paratrooper rifle, the mainline paratrooper arm at the time, breaks down into two segments; thus, the Japanese M1 copy meets existing IJN paratrooper command requirements. Very importantly, as development of the rifle progressed to the production design, features “c” and “d” were replaced by the tried-and-true equivalent features on the U.S. M1 rifle. Only the novel features “a,” “b” and “e” remained.

A U.S. Army Ordnance bulletin put together in late 1945 presents perhaps the most accurate assessment of Washino’s production effort. The report states that the factory had no production machinery, so it was assembling rifles from parts that were most likely furnished by Yokosuka Arsenal.

Second Variation Experimental Type 4 Rifle

As far as we know, the second variation of the experimental Type 4 rifle exists only in drawing form today. High-quality assembly drawings of the rifle have been recovered from the archives of the Japan Self Defense Force (JSDF) in Tokyo. The drawings show most all of the features of the final configuration of the Type 4, including the revised magazine box with external cap integral with the magazine floorplate. The action-locking features of the first variation are retained, which are locking hooks integral with the trigger guard that engage similar lugs on the backside of the receiver magazine box as the trigger guard is rotated to the closed position, thus locking the rifle components together. The drawing is very detailed and appears to be a production-level drawing, not one of an experimental rifle. It is complete to the point of including accessories, such as a cleaning apparatus and paratrooper accessories such as a waist ammunition belt. So, either the design group was jumping ahead without proof of successful testing, or initial testing with the first prototype had exceeded expectations. No examples of the second variation have been reported, so whether this specimen was actually built is unknown.

Third Variation Experimental Type 4 Rifle

It is only a small step to reach the final Type 4 configuration. The drawings for the second variation incorporate most of the changes to reach the final stage except for the locking mechanism. The third variation substitutes the locking features of the U.S. M1 rifle. Locking lugs on the M1 are configured differently, and enter recesses in the receiver. Rotating and latching the trigger guard locks the assembly together. Keep in mind that the Japanese version had heretofore featured locking lugs external to the magazine box. The IJN may have switched to the M1 design simply to guarantee success in a timely fashion by minimizing any unforeseen development problems.

One example of the experimental third variation has been examined. Typical of the Japanese procedure in serializing experimental production, the rifle exhibits only a small numeral “4” on the front top of the receiver. No other components are marked. Only one specimen so marked has been reported. The rifle shows results of extensive testing with serious bore wear.

Type 4 Pre-Production Rifle For Field Test

With the final configuration set for production, the rifle was adopted by the IJN as the Type 4 rifle. Examples were hurriedly fabricated at Yokosuka Naval Arsenal for field testing prior to mass production. They were reportedly shipped to ground units in China, the islands and to the IJN paratroop command within Japan for extended field tests. That plan could involve a sizable number of rifles, but, most likely, only a handful were distributed.

These rifles exhibited model, arsenal of production and serial numbers on the receiver, along with the month and year of production. The receiver markings on the two examined are inconsistent and hand-engraved, showing a lack of overall process control and also illustrating how fast the program was moving. The rifle with Serial No. 6 has the Yokosuka identification on the line with date of manufacture, while Serial No. 5 has the Yokosuka identification on the line with the serial number. Specimen Serial No. 6 had been examined and found to have all parts matched to the serial number. Only two specimens of this type have been reported.

Type 4 Production (Washino Factory)

Testing of the prototype rifles revealed problems with parts breakage, insufficient recoil and associated feeding difficulties. Even with these problems, testing was considered successful enough to initiate production. Yokosuka Naval Arsenal was not able to support production, so plans were made to shift the work to a private company: Washino Kikai Co., in Aichi-ken.

A U.S. Army Ordnance bulletin put together in late 1945 presents perhaps the most accurate assessment of Washino’s production effort. The report states that the factory had no production machinery, so it was assembling rifles from parts which were most likely furnished by Yokosuka Arsenal. Furthermore, only 50 rifles had been assembled at the war’s end, even though parts for 150 rifles were on hand. None of the rifles had passed final inspection, and the rifles were found in various stages of completion at the factory.

Production of the rifle had stopped prior to war’s end because of functioning problems identified as insufficient recoil from the less powerful 7.7 mm cartridge to eject and chamber another round from the magazine of tested rifles. At Washino Kikai Co., personnel were production-oriented, and no engineer was on staff to solve test problems that may have been encountered, so the company was awaiting instructions from Yokosuka on how to correct the problem and proceed.

While Type 4 production was at a standstill, new orders were received from the IJN to cease production of the rifle in favor of a new aircraft engine contract. When U.S. Ordnance personnel visited the Washino factory in late 1945 after the cessation of hostilities, they found production in the process of switching to an aircraft engine. Even though the production line was being changed, special machinery was at the same time arriving at the factory for rifle parts production. All this illustrates late-war confusion in Japanese production.

I have catalogued 33 Washino-assembled rifles. None are marked externally, indicating no final inspection, but each has an assembly number on the underside of the receiver to match up parts at the assembly stage. The addition of serial number and final inspection symbols were to be added only after successful testing of each rifle. The highest assembly number recorded is No. 58, and that corresponds nicely with U.S. Army Ordnance reported data showing 50 assembled rifles found at the factory at war’s end.

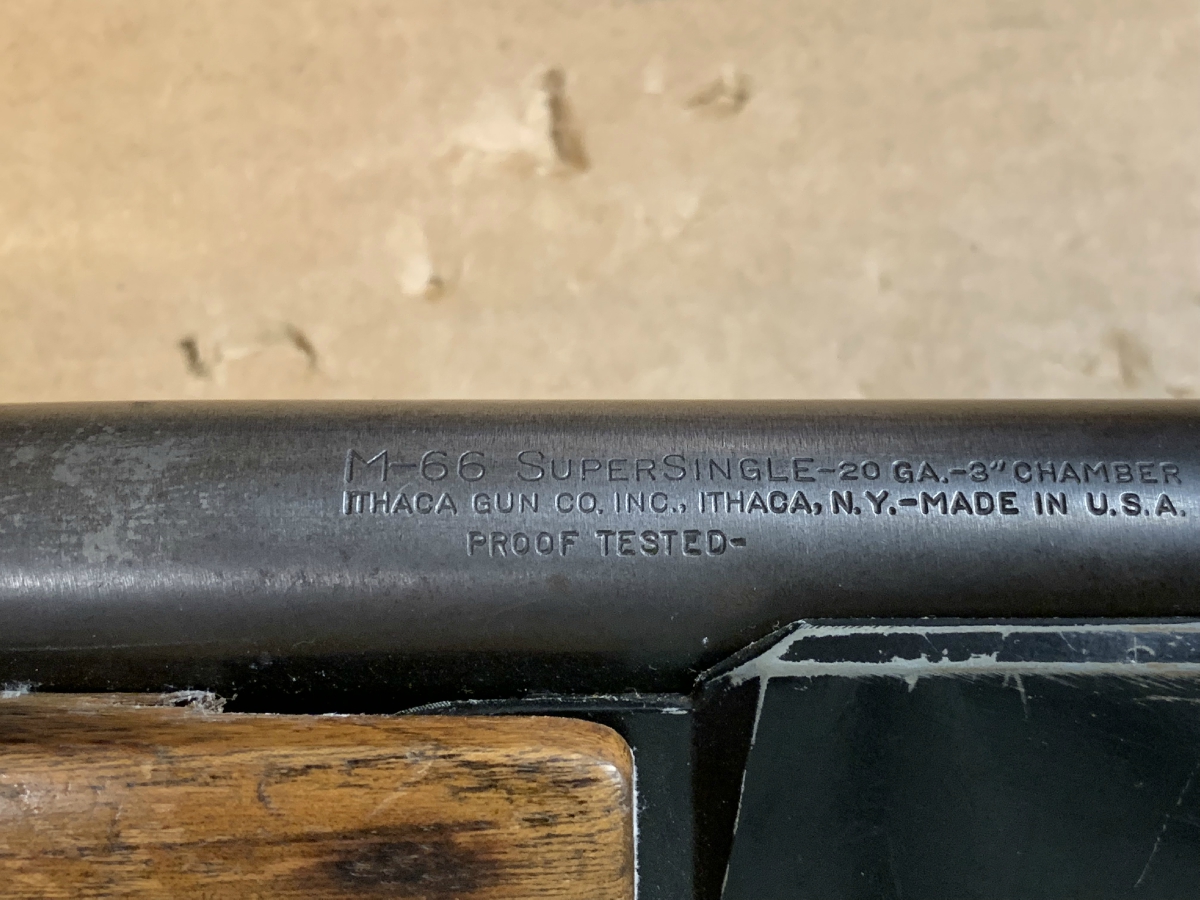

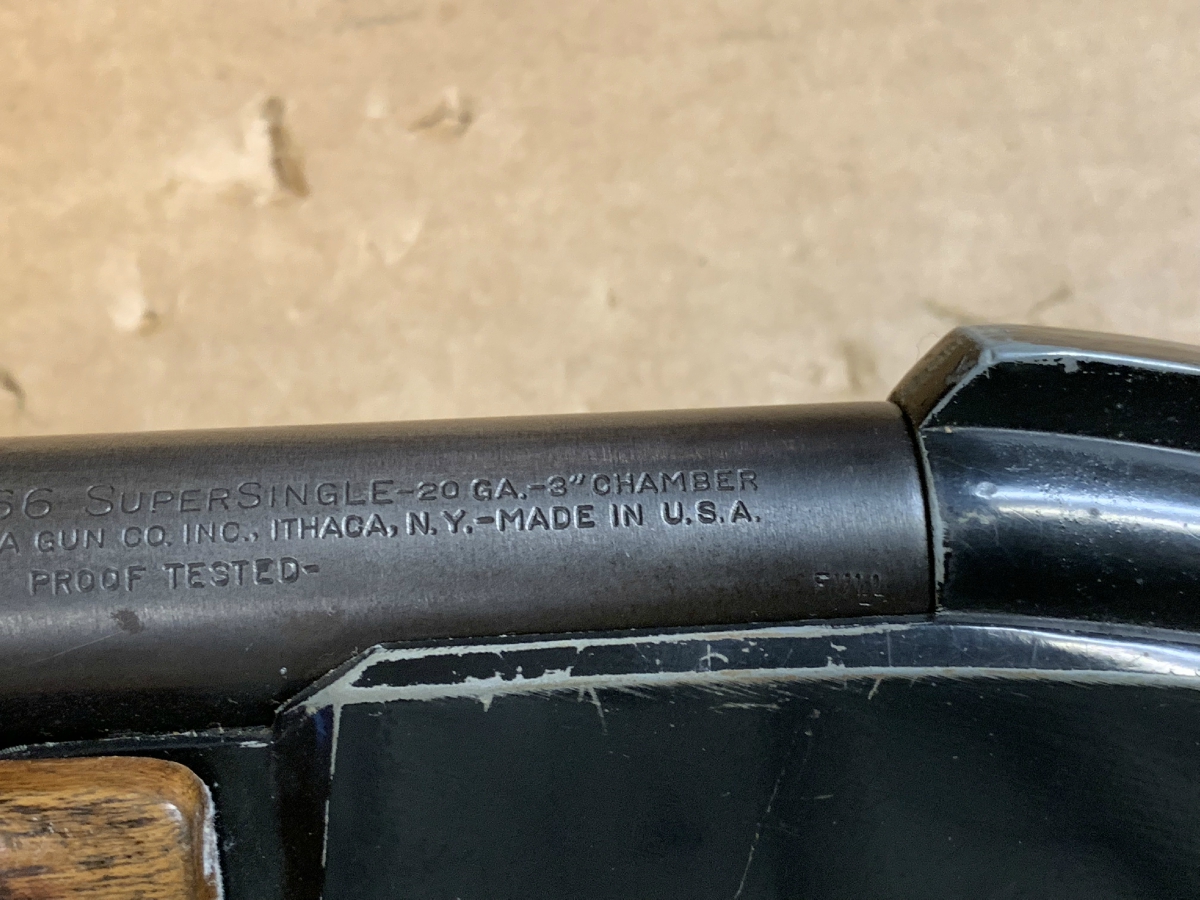

Yeah it’s ugly & cheap. But sometimes that is all one needs or can afford at the time! Plus I am willing to bet that it can get the job done. Just saying, Grumpy

It should be obvious to anyone not ideologically blinkered that the Los Angeles Times has wed itself to the social justice cause, so inextricably so that no one at the paper seems cognizant of the fact that social justice, with its appeals for compassion for criminals, comes at the expense of actual justice and the welfare of crime victims.

The Los Angeles Times is hardly alone in its descent into woke activism. Indeed, the entire mainstream media complex seems to have abandoned its pretense of objectivity (and it has long been just a pretense) in favor of open left-wing activism. Nowhere is this more evident than in the reporting on issues relating to crime.

On Tuesday, the L.A. Times ran a story concerning one of the paper’s favorite ongoing themes, to wit, allegations of bias on the part of Los Angeles Police Department officers patrolling the more crime-ridden sections of the city. “LAPD admits it made hundreds more traffic stops in South L.A. than it told The Times,” reads the headline, reflecting the glee no doubt shared at the newspaper that the Department had been caught providing inaccurate data regarding this contentious issue.

This is not to excuse providing bad data to the Times, but the story itself seems to be more concerned with the “gotcha” aspect than with the far more important issue underlying the data, which is the problem of violent crime in Los Angeles, particularly in South L.A.

What’s more, the story is a muddle of unclear information from which the reader is unable to draw a sound conclusion. Times staff writer Kevin Rector opens the story with the “gotcha.” “Los Angeles Police Department officials earlier this month downplayed a return to controversial investigative traffic stops in South L.A.” he writes, “in part by telling The Times that the number of stops was dramatically lower than it used to be — with just 74 stops so far this year.” He goes on to cite the belatedly revealed accurate data. “But on Tuesday,” Rector writes, “LAPD Chief Michel Moore told the L.A. Police Commission that figure was wrong, and that the true count was more than eight times as high, with 639 stops having been conducted.”

Only by reading deep into the story, and by reading a linked Feb. 12 article, also by Rector, can the reader learn that it is stops by Metropolitan Division officers that is being discussed. Officers assigned Metropolitan Division, or Metro, do not respond to routine radio calls. Rather, they are traditionally deployed to inhibit crime in those areas of the city where it is most disruptive, which in Los Angeles means the four patrol divisions that make up South L.A.: Newton, Southwest, 77thStreet, and Southeast. (I worked at all of these stations at various times in my LAPD career.) L.A. Mayor Eric Garcetti and LAPD Chief Michel Moore were characteristically spineless and curtailed the patrols in 2019 after the L.A. Times ran stories claiming the tactic “disproportionately affected Black and Latino drivers.”

It would have been malfeasance on the part of the police had the stops not done so. Consider: these four divisions (of the LAPD’s total of 21) are home to about 640,000 people, or 16 percent of the city’s population, yet they accounted for 44 percent of the 349 homicides investigated by the LAPD in 2020. Nearly every single resident of these areas is black or Hispanic, as were the homicide victims and those who killed them.

The LAPD no longer publishes the racial breakdown of homicide victims and suspects as it once did, but it’s fair to assume that the city’s homicide figures run parallel to those of Los Angeles County, of which L.A. is by far the largest city and biggest driver of crime numbers. (Los Angeles County has about 10 million residents, of whom about 4 million live in the city of L.A.) According to the L.A. Times Homicide Report, last year there were 691 homicides committed in L.A. County, excluding those killed by police. Of these victims, 50 percent were Hispanic, 35 percent were black, 10 percent were white, and 5 percent were Asian. The county’s population is 47 percent Hispanic, 26 percent white, 15 percent Asian, and 9 percent black.

From these numbers one can see that homicide figures do not track perfectly with each racial and ethnic group’s share of the overall population. Yet the Los Angeles Times continues to insist something nefarious is afoot when LAPD stop figures align more closely with crime patterns than with population data. “The move to reinstate ‘investigative stops,’” writes Kevin Rector in the Feb. 12 story, “immediately raised concerns among some longtime police observers at a time of increased scrutiny over LAPD tactics in communities of color.”

As is now oh so fashionable, these “longtime police observers,” to include the writers and editors at the Los Angeles Times, apparently, are more discomfited by the prospect of police officers conducting investigative stops in high-crime neighborhoods than they are by the crime itself. It is precisely in those “communities of color” that law-abiding residents are most in need of protection from those who would prey on them.

Black Chicagoans Eviscerate Black Lives Matter Narrative, Booting Activists From Their Neighborhood

And yet the L.A. Times, along with nearly any other media outlet you can name, continues to peddle the lie – there is no better word for it – that what is most injurious to these “communities of color” is police harassment rather than the crime police seek to prevent.

How else to explain the paper’s uncritical devotion to George Gascón, L.A. County’s new district attorney and the latest of the George Soros-funded “progressive” prosecutors elected to office? The Times endorsed Gascón over incumbent Jackie Lacey last fall, and in the last two months has printed two editorials (here and here) defending Gascón and his lenient policies, the effects of which are fewer criminals sent to prison and shorter sentences for those who are.

Granted, Gascón was only recently elected, and one may argue, as does the L.A. Times, that his policies should be given time to bear their intended fruit. But what evidence is there that the fruit will be any less poisonous than that already produced in cities where progressive prosecutors have held office for longer? Larry Krasner took office as district attorney in Philadelphia on Jan. 1, 2018, and homicides in that city rose by 8 percent that year. Homicides declined by 1 percent in 2019, offering a hopeful sign, but then rose by 35 percent in 2020. They’re up an additional 33 percent so far this year.

In Chicago, Kim Foxx ran on a progressive platform and took office as state’s attorney for Cook County on Dec. 1, 2016, and was re-elected in 2020. Homicides in the city declined from 769 in 2016 to 492 in 2019, but then increased horrifyingly to 792 last year.

Chesa Boudin, district attorney for San Francisco, is the son of Weather Underground members and convicted murderers Kathy Boudin and David Gilbert, a lineage that would understandably warp one’s views on law and order. He was elected in 2019 after promising progressive reforms to the criminal justice system in that most progressive of cities. The results so far? San Francisco saw a 17 percent increase in homicides in 2020.

In short, there is precious little to suggest the progressive policies instituted by this new wave of prosecutors have brought about anything but a rising tide of bloodshed among the very populations they claim to champion. The only people profiting from all this “progress” are the undertakers.

It was the tough-on-crime measures enacted in the early and mid-1990s that stemmed the rising tide of violence seen across the country (2,245 homicides in New York City in 1990, 1,092 in Los Angeles and 943 in Chicago in 1992) and brought about the relative placidity of recent years. Those gains have been reversed with staggering speed, all with the blessing of these progressive prosecutors and their enablers in academia and media outlets like the Los Angeles Times, all of whom share the naive, even childlike belief that showing compassion for the cruel will make them less so.

You can run only so far from reality. Like a bullet, it catches up with you quickly

The myriad selection of rifle cartridges today has a metric ton of overlap, duplication, and some downright silly designs. Some of these designs boast wonderful claims, but not all of them measure up. In order to be overrated, you have to be rated at all, so that leaves some of the more obscure designs off the menu.

I’m well aware that I’m going to be taking a lot of flak for this article, no matter which cartridges I were to pick, so let me give you some details to start with. When you sit down to make your voodoo doll of me, you need to be as realistic as possible, I’m six feet tall, bald, blue eyes, and the goatee is graying. Accuracy counts in the voodoo-curse world as well.

That said, I have to pick five, and I know someone will come away with hurt feelings, but I’m going to throw caution to wind and do this anyway. “Overrated” is a tough term. It doesn’t mean that the cartridges I’m going to pick are bad, or even that they don’t work, it means that I feel that the glorification of them may not live up to the actual performance. Let’s roll.

1. .300 Weatherby Magnum

I can feel the hot needles already. Roy Weatherby had a passion for the pursuit of velocity, and in some instances it made for a fantastic cartridge. However, the .300 Weatherby, based on a blown-out .300 H&H case, and featuring Roy’s signature double-radius shoulder, may have been the hottest on the market in the 1950’s, but it has been pushed off the stage. In my opinion, you can get field performance out of a .300 Winchester Magnum that is so close the game animals will never know the difference. Add in the costly ammunition and component brass, as well as the ramped-up recoil, and the scales lean even harder toward the Winchester case. If you want to really move .30 caliber bullets in a magnum length action, look to the .300 RUM or .30-378 Weatherby, just don’t shoot anything you intend to eat at close range.

2. .270 Winchester Short Magnum

Why do my feet feel like they’re on fire? When you have a cartridge that is as flat shooting and hard hitting as the venerable .270 Winchester, improving upon it isn’t easy. The Winchester Short Magnum series of cartridges have their own unique set of issues (they’re very finicky to reload for, not to mention the feeding issues), but to try and push the bullets even faster, out of a shorter and lighter rifle with more recoil, doesn’t make a ton of sense to me. The .270 Winchester is a fantastic long-range cartridge. The longer bullets start to eat up case capacity, and the caliber is generally limited to bullets that top out at 150 grains. The .270 WSM is too much of a good thing, in my opinion.

3. .220 Swift

Yes sir, that was a needle in my eyeball. Good thing I have a spare. How dare I insult the .22 centerfire velocity king? Well, here’s my thinking. The .22-250 Remington, which performs around 150 to 200 fps slower than the Swift, will hit distant targets very well, with less powder, a shorter action, and is every bit as accurate as the Swift cartridge is. Not to mention, the .22-250 doesn’t have that rim, which can make for feeding problems in a magazine rifle. I know, the Swift hits that illustrious 4,000 fps with 55 grain bullets, but the 3,800 fps generated by the .22-250 is more than enough for me.

4. .458 Winchester Magnum

The idea of replicating the ballistics of the .450 Nitro Express, in an easy-to-produce bolt action rifle, was a very sound one. However, Winchester’s claim has historically fallen short of the mark. The engineers shortened the blown out .375 H&H case to fit in a long-action receiver, and in the same stroke reduced case capacity to the point that it became a problem. If you’ve ever tried to handload for the .458, I’m sure the thought of compressing powder with a pogo stick (please DO NOT try this, it’s humor) has crossed your mind. Look to Jack Lott’s full-length design, as it’s much easier to achieve the velocities that Winchester intended when handloading, and there are more than enough factory loads available. Almost all of the African Professional Hunters I’ve met re-chamber their .458 Winchester into a a .458 Lott, or are saving up to do so.

5. .223 Remington

Yes, I said it. Look, the .223 works, and works well for most of its intended purposes. But, I truly believe if the U.S. Government hadn’t smiled upon it, the cartridge would have a small fraction of the followers it does today. I hear shooters tell me all the time about how it is a miracle-wrought-in-brass-and-lead, and proceed to boast of its heretofore unheard-of capabilities. I feel, for the hunters, that a .222 Remington is more accurate for close ranges, and the .22-250 Remington has a huge advantage in the velocity and accuracy department at all ranges. The .223, with the right twist rate, can use the heavier 69 and 77 grain bullets, where the slow twist of the .22-250 limits it to 55 or maybe 60 grains tops, but for me, the .223 isn’t the Holy Grail of cartridges that so many profess it to be.

There you have it, take it for what it’s worth, and let voodoo curses and author-bashing commence.

Editor’s Note: Don’t worry, Phil’s already covered the industry’s most underrated rifle cartridges, too. Check that out right here!