Month: January 2021

Debunking the Myth of Southern Hegemony: Southerners who Stayed Loyal to the US in the Civil War

On April 1, seven states – Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, Texas, and Virginia – will begin their celebration of Confederate Heritage Month. As a counter to this narrative of southern hegemony, I’d like to take a moment and celebrate those Southerners who remained loyal to the United States and who –

if they were currently serving U.S. military officers at the time – did not break their oaths. The war is often portrayed as a North versus South narrative. As we will see, it was far more complex, with the Southern states being far from united in their cause.

First off, we have Virginia-native General Winfield Scott, senior officer in the U.S. Army at the outset of the Civil War. A veteran of the War of 1812 and the Mexican War, his strategy eventually won the war and who kept his oath to his country. When Robert E. Lee turned down Scott’s offer to command the land forces being assembled to put down the rebellion, Scott said “I have no room in my army for equivocal men.”

Nicknamed “Old Fuss and Feathers,” he was considered one of the greatest strategic minds of his day.

Next, Alabama brothers David and William Birney. David would rise to division and corps command while William commanded black troops in combat. Both rose to the rank of major general and managed to be true to their country – despite their state of origin.

One of my favorites: Solomon Meredith, born in North Carolina but who later moved to Indiana, “Long Sol” would eventually command the Iron Brigade, the only all-Western brigade in the Army of the Potomac, some of the toughest fighters in the army.

Then there’s Georgian Montgomery Meigs. West Pointer, engineer, and a compatriot of Robert E. Lee. At secession, he stayed true to the US, became the chief logistician of the US Army (Secretary of State Seward called him the key to victory), and – in an ultimate act of defiance – established the U.S. National Cemetery at Arlington literally in Lee’s back yard. Sure, it might be petty but the man also lost his son, Lieut. John Rodgers Meigs, to the war, and that does something to a man.

And of course, Virginia-born George C. Thomas, also known as the “Sledge of Nashville” and the “Rock of Chickamauga.” With nicknames like that, you have to be a badass. Which he was. Thomas was disowned by his family for staying true to the US.

One of the most brilliant strategic minds of the war, Thomas often gets little praise although U.S. Grant considered him one of his best generals.

There’s also almost-southern John Gibbon, who grew up in North Carolina in a slave-owning family. A career Army officer, he stayed true to the U.S. after three of his brothers took up arms against it. He was an artillerist and the first commander of the Iron Brigade. In August of 1862, the Iron Brigade destroyed “Stonewall” Jackson’s division almost by themselves. Later on, it would be his division that halted Pickett at Gettysburg.

Georgian John C. Fremont, noted explorer and politician, who was given command of the Department of the West. A better self-publicist than he was a good general, Fremont did one thing no one else had done – trust some guy named Ulysses S. Grant to be a good general.

Missouri-born Frederick Tracy Dent was a career Army officer who decided against turning on his country and ended up as aide-de-camp to Ulysses S. Grant. It helps when your sister is married to the commanding general, of course.

I’ve been too Army-centric. How about the good gentleman from Tennessee, David “Damn the Torpedoes” Farragut? He thumbed his nose at the rebellion and went on to become the victor of New Orleans and Mobile Bay, forcing the U.S. Navy to create the rank of full admiral for him.

Next is South Carolinian Stephen Hurlbut who became commander of the Department of the Gulf in 1864. In 1861, he was sent to South Carolina by Lincoln to try to get a feel for the sentiment of the people there. His response: “There is positively nothing to appeal to — the Sentiment of National Patriotism always feeble in Carolina, has been extinguished and overridden by the acknowledged doctrine of the paramount allegiance to the State. False political economy diligently taught for years has now become an axiom & merchants and business men believe and act upon the belief — that great growth of trade and expansion of material prosperity will & must follow the Establishment of a Southern Republic. They expect a golden era, when Charleston shall be a great commercial emporium & control for the South as New York does for the North.”

General John Buford was born in Kentucky and made a career in the regular Army. When his state became divided in the Civil War, Buford stayed true to the U.S. Commanding a cavalry division at Gettysburg, his actions to delay the Rebels were critical in preserving key terrain. He is known as being one of the fathers of modern cavalry because of his skill at reconnaissance, counter-reconnaissance, and screening.

Joseph Holt from Kentucky – anti slavery and pro Union – was the Judge Advocate General for the U.S. Army and later was the chief prosecutor in the Lincoln Assassination trial

John Ancrum (what a name) Winslow was born in North Carolina but upheld his oath and stayed with the U.S. Navy during the Civil War. On June 14, 1864 he commanded the USS Kearsarge in her victory over the notorious rebel commerce raider CSS Alabama.

Enough with the dudes, though. Elizabeth van Lew of Richmond, Virginia, spent all her available money freeing slaves. When war came she remained loyal and set up a spy ring in Richmond, helped rescue US soldiers in Libby prison, and raised the first US flag over the city after it fell.

Who’s this fellow? Oh, just the Virginian Rear Admiral Samuel Phillips Lee, U.S. Navy. Yes, THAT Lee. Robert’s cousin. Unlike his cousin, Samuel remained true to his nation and served honorably through the Civil War.

Oh, and look, it’s Major John Fitzgerald Lee. Yes, that’s right, another cousin of Bobby Lee. John F. allegedly stated, “There was no Virginia in my commission, only the United States.” He would serve as Judge Advocate for the U.S. Army in the Civil War

Unfortunately, there’s no picture of Virginian Louis Henry Marshall, Robert E Lee’s nephew, who stayed true to his oath and served as aide de camp to U.S .General John Pope during the Civil War. Bobby Lee’s sister and sister-in-law both stayed loyal to the U.S. – belying the myth that Lee could do nothing but go with Virginia when it turned against the U.S.

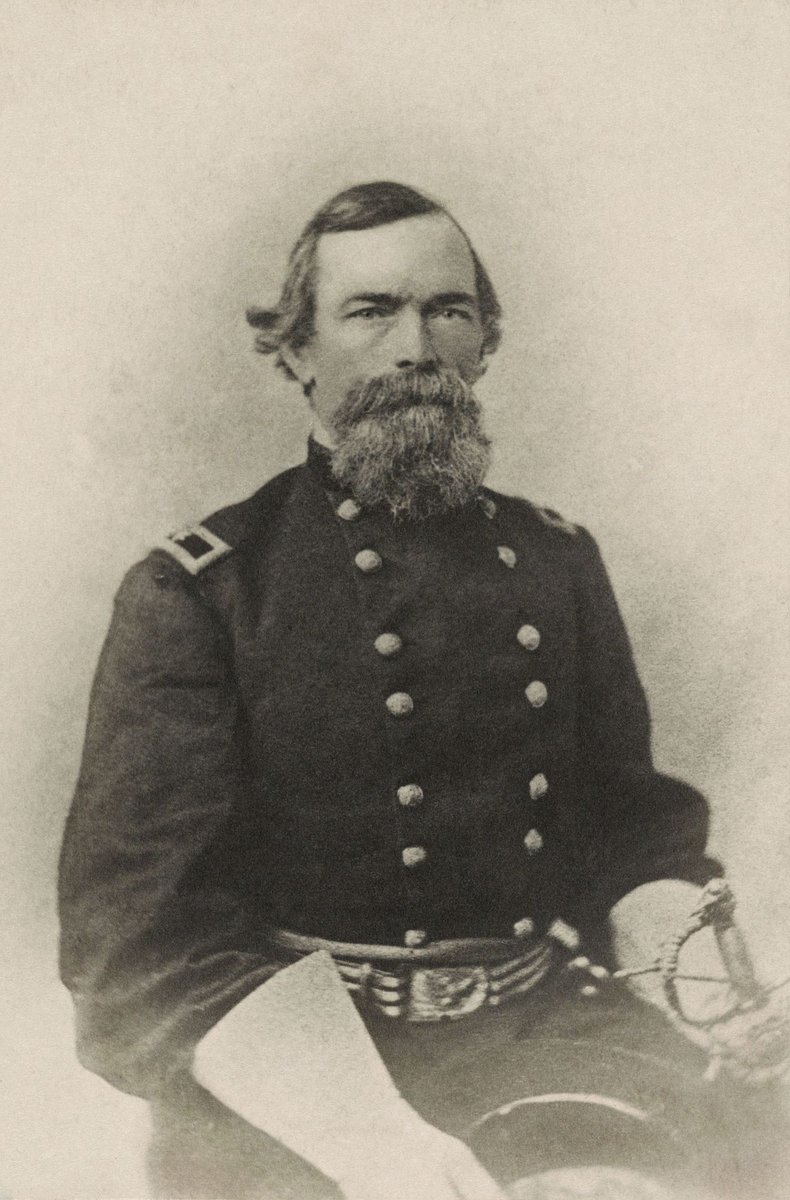

This is Brigadier General Philip St George Cooke, a Virginian who stayed loyal to the U.S. Constitution even though his son-in-law JEB Stuart turned his back on it. Stuart said his father-in-law would regret his choice, but once, and that was always; but then, Stuart got killed in 1864 so what did he know.

Virginian and West Pointer John Davidson was offered a position in the Confederate Army. He declined and stayed true to his oath, fighting through the duration of the war in both the east and west. After the war, served as lieutenant colonel in the 10th Cavalry “Buffalo Soldiers” – an all-black unit.

Next is Major General Alexander Dyer, a Virginian, who commanded the Springfield Arsenal during the war, boosting output so much that he was eventually made Chief of Ordnance for the U.S. Army.

West Pointer and Tennessean Alvan C. Gillem didn’t betray his country at the outset of the war, serving with George H. Thomas and rising to the rank of brigadier general.

Son of a Virginian career politician, John Newton stayed loyal to the U.S. when war began. An engineer, Newton would lead units in combat, taking over the I Corps when Major General John Reynolds was killed at Gettysburg. After the war, he became Chief of Engineers for the Army. Essayons!

Jesse Reno was born in then-Virginia, now West Virginia. He was a West Point classmate of Stonewall Jackson who elected not to betray his country and who rose to rank of major general. Known as a soldier’s soldier, he was killed in action in 1862.

Next up is Edmund J. Davis. Born in Florida, raised in Texas, he fought against secession as a judge before a mob forced him to flee the state. He then enlisted in the US Army and rose to the rank of brigadier general. After the war he became Governor of Texas, fighting for civil rights; as part of this effort, he hired African-American law enforcement officers into the Texas State Police.

George D. Ramsay was of an old Virginian family, yet disdained treason’s call and remained loyal. A regular Army man, he rocketed from major to brigadier general in just a few years, becoming Chief of Ordnance for the U.S .Army until 1864.

When the Civil War began, Virginian William R. Terrill wired D.C., “I am now and ever will be true to my oath and my country. No one has any authority to tender my resignation. I will be in Washington as soon as possible.” He was killed in action at Perryville, leading his brigade.

John C. Black from Mississippi enlisted into the U.S. Army two days after Fort Sumter. He was wounded in action at Prairie Grove, Arkansas in 1862. For this action he was later awarded the Medal of Honor. After the war, he became a Congressman for Illinois.

John B .McIntosh, from Florida, served in the U.S. Navy before the Civil War. When the Civil War began he joined the U.S. Army and was leading a brigade of cavalry by the time of Gettysburg. Here, he played a major role in stopping the Confederate cavalry action on July 3. He lost a leg in 1864.

John P. Bankhead was born in the heartbed of secession, South Carolina, of an old South Carolina and Virginian family. He remained true to his Navy and the United States, as did one brother, again demonstrating that it was *always* a choice.

Virginian William T. Ward moved to Kentucky as a young man where he represented the state in Congress in the 1850s. When war came, Ward remained loyal to the U.S .and rose to the rank of major general. He accompanied Sherman on his March to the Sea.

This is the Napoleon Bonaparte Buford, from Tennessee, half brother of John Buford. Like his half brother, he stayed loyal to the US. He commanded troops in the Western theater through the Civil War.

As we can see, it was hardly a unanimous decision for individuals to choose between their Nation and their State. In fact, one quarter of the entire U.S. Army during the Civil War was made up of Unionist southerners and those from the border states. Forty percent of West Pointers from Virginia stuck to their oaths. Unionists dominated the mountainous areas of the South, sending soldiers north, helping escapees from Confederate prisons, and raiding Confederate supply lines. One entire section of Virginia remained loyal – we know this today as the state of West Virginia.

So why then do we have images of the South as one, united entity, fighting against a purely Northern, largely immigrant invader? Narrative, mainly. And not a narrative that was mere happenstance either.

George H. Thomas noted in 1868, “[T]he greatest efforts made by the defeated insurgents since the close of the war have been to promulgate the idea that the cause of liberty, justice, humanity, equality, and all the calendar of the virtues of freedom, suffered violence and wrong when the effort for southern independence failed. This is, of course, intended as a species of political cant, whereby the crime of treason might be covered with a counterfeit varnish of patriotism, so that the precipitators of the rebellion might go down in history hand in hand with the defenders of the government, thus wiping out with their own hands their own stains; a species of self-forgiveness amazing in its effrontery, when it is considered that life and property—justly forfeited by the laws of the country, of war, and of nations, through the magnanimity of the government and people—was not exacted from them. “

The Confederate States of America cost our nation dearly, in blood and treasure. Those that promulgated its rise, carried its spirit into the 20th century as Jim Crow legislation, the Klan, and the Myth of the Lost Cause. That, therefore, is the true heritage of the Confederacy – and not one that should be honored. What we can do, however, is take note of those individuals who did not bow to the mob and stayed true to their oaths. We can only hope that we would have such constancy for the Republic.

Enjoy what you just read? Please share on social media or email utilizing the buttons below.

About the Author: Angry Staff Officer is an Army engineer officer who is adrift in a sea of doctrine and staff operations and uses writing as a means to retain his sanity. He also collaborates on a podcast with Adin Dobkin entitled War Stories, which examines key moments in the history of warfare. Support this blog’s Patreon here.

Cover Photo: George H. Thomas, Library of Congress. Thanks to the Library of Congress and the National Archives for the photos for this post.

Before you take your new AR-15 out for target practice or into the field to do some hunting, the first thing you will need to do is zero in the iron-sights.

All rifles and upper halves with sights installed from the factory are bore sighted to 25 yards. The process takes some patience, but you will be spending valuable time getting to know your new rifle while making it as accurate as possible.

This article focuses on most flip-up and stationary sights. Sighting in with the carry handle is a bit more complicated.

How the Front and Rear Sights Work

When it comes to zeroing the iron-sights on your AR-15, it’s important to understand what the front and rear sights do. The front sight is responsible for elevation, or how high or low the point of impact is compared to the point of aim. The position of the rear sight will determine the windage, or whether your shot will hit to the left or right of the target.

The First Step: Finding Mechanical Zero

Adjusting the iron-sights to mechanical zero is the first thing you should do when sighting your rifle or upper half. However, if it was purchased directly from Stag Arms, you can skip this step. Start by rotating the front sight post up or down until the base of the post is flush with the sight well. Once that is done, move on to the rear sight.

Most sights on an AR-15 have both a large and a small aperture. The large aperture is used for close up shooting and typically has a line that you can use to align it with hash marks along the bottom of the rear sight. If the aperture doesn’t have a mark, simply rotate the windage knob until the aperture is all the way to the left or right.

After that, turn it all the way in the opposite direction, counting clicks as you go. Divide the number of clicks by two to determine the center of the rear sight. Then, move the rear sight that number of clicks from one of the sides.

Using The Stag Arms Sighting Target

Once the iron-sights are mechanically zeroed, or if you received it from our factory, you can start adjusting them for accuracy. Fire groups of five shots at the target from a distance of 25 yards. Find the center of your groupings and measure from there to the central vertical and horizontal lines in order to determine how far you need to adjust the sights. If the shots appear all over the target and aren’t in groups, focus on the shooting fundamentals until you achieve groups.

All the lines on our sighting target are in 1” increments from the center of the bullseye. To move your groupings to the left, turn the windage knob on the rear sight to the left and to the right to move your grouping to the right on the target. Looking from the top of the sight, the front sight post will need to be turned clockwise to raise groupings and counter-clockwise to lower them as they appear on the target.

Basically, you will want to move the rear sight in the direction you want your shots to appear on the target, and you will want to move the front sight in the opposite direction that you want the shots to appear on the target.

Print out our sighting target here.

Photo Courtesy of: www.ar15news.com

Topics: Rifle Sights, zero in the iron-sights, AR-15 Sights

ADVICE FOR LIFE

I will hereby lay claim to the spurious honor of being the world’s foremost “good example of a bad example,” especially in the arena of personal safety.

Through a lifetime spent as a cop, adventurer and shooter, I’ve managed to make nearly every mistake possible yet lived to tell about it. Fortunately, I’m also a testament to why luck and a benevolent Supreme Deity are a nice fallback when you’re dumb. And — let’s be frank — almost all of us are dumb once in a while.

Well, maybe not Massad Ayoob, but pretty much everybody else does foolish things on occasion.

This overview of personal (dis)qualification is given to explain why I have both the temerity and experience to present my own collection of the 50 most important rules of personal safety. They’re not the only principles for dealing with danger, especially of the social and interpersonal variety, but I think they’re a good start.

Some of this information comes firsthand from the countless “real-deal” folks I’ve had the honor of knowing, some comes from training, still more comes from direct observation of rapidly-coagulating pools of blood and the remainder was learned from The University of Life, School of Hard Knocks, Bachelor of Science in Blunt Trauma and Gunshot Wounds. I’ll allow some of these points are a bit facetious and snarky, but then again, so is life.

So, without further ado, I present “My 50 Rules for Life.”

1. There is no “ultimate manstopper” except perhaps a 105mm High Explosive shell.

2. Shot placement is far more important than caliber, energy, velocity, momentum or advertising hype. Remember the .22 Long Rifle has killed things as large as grizzly bears while a miss with a .458 Win does nothing but punch holes in the blue sky.

3. Wearing “cool guy gear” doesn’t make you cool. Brand-new “cool guy gear” will make you look like a poser. A plate carrier — with multiple witty “morale” patches, of course — worn on the range merely for visual effect when you’ve never actually worn one “in the field” makes you an Ultra-poser with Extra Posing Sauce.

4. The bigger the cleavage on the advertising copy, generally the worse the product. Nowadays, with political-correctness being in fashion, you see less and less of this. Of course, some of us sure miss the old days.

5. Fear is natural. Embrace it and learn to use it to your advantage. Invite it into your home, make it dinner and let it drink your best bourbon because being “fearless” means taking stupid risks.

6. The more combat a person has seen, the less likely they are to talk about it.

7. Scars are nature’s way of saying “I screwed up.” They also make for good graphic training aids and sometimes can even get you a free beer, though the cost/benefit ratio is not usually worth it.

8. Courage is the first requirement of success in a crisis. It’s easy to “talk the talk” but you should really test your courage periodically in some way to make sure it hasn’t died of inattention — or never really existed in the first place.

9. Even a ruggedized, fully redundant, satellite-enhanced, broadband-data-capable multimillion-dollar tactical communication network will break down under adverse conditions such as dew or nightfall.

10. A sense of humor will get you through anything from a gunshot wound to a divorce. It’s hard to think of droll comments when suffering a sucking chest wound during court proceedings, but it does help lighten the mood.

11. Everything on the internet should be considered “For Entertainment Purposes Only.” By now, hopefully everyone has realized “SuperDeathSEALKillerCommando99” on an internet forum is probably a morbidly-obese 13-year-old gamer on a laptop.

12. Gun store clerks come in two flavors: aficionados and salesmen. It’s your job to know the difference.

13. Any product with the word “miracle” in the title isn’t. Any shooting technique named after its developer — as named by said developer — is probably the same thing.

14. Trust no one except your mother. Keep an eye on her.

15. Being alert will prevent 99% of problems. If you are alert, you’ll be much more ready for the remaining 1% which are a problem.

16. Do unto others as they would do unto you; just make sure you do it first.

17. Death loves a braggart. Everyone else loves to see him get kicked in the groin — therefore, don’t ever brag about your tacti-cool-ness. See rule #3 and #6.

18. There is no such thing as a fair fight. If you fight, don’t be fair. This is why many old, slow, creaky guys are still very dangerous.

19. We should do more to include our loved ones in crisis preparation and training.

20. If you know it all — you don’t.

21. There is someone who is tougher, faster, a better shot or just plain luckier somewhere out there in the world. Remember this when considering a fight you could otherwise avoid.

22. The corollary to #21: There is no shame in avoiding a problem. This is otherwise known as “wisdom.”

23. The first rule of knife fighting is “Don’t get into a knife fight.” If you are in a knife fight, the best self-defense technique is applying a magazine full of large-caliber bullets as quickly as possible.

24. Anything and everything can and will fail at the worse possible moment. Plaintiff’s Exhibit #1 — Viagra.

25. We could all use a little more cardiovascular exercise.

26. When in doubt, doubt. Your “little inner voice” is world’s smarter than you give it credit for.

27. Virtually everything you see on commercial television is staged. Everything … as in everything.

28. If you don’t practice a movement at least 500 times (some say 2,000), you will never perform it correctly under stress. This is an iron-clad, unbreakable rule we all ignore.

29. A vehicle will kill you just as dead as a high-powered rifle. Always respect traffic.

30. No instructor is God. Some can reach demigod status after decades, many of them are pretty good and few of them should be prosecuted for false advertising. Beware the Cult of Personality, especially if you are new to firearms training classes — almost everybody seems brilliant when you’re new!

31. There is nothing wrong with blued guns, revolvers, leather holsters or firearms without “cutting-edge aerospace technology.” Then again, there’s nothing wrong with “black guns” either. Don’t be dogmatic.

32. The human brain is the deadliest weapon ever invented.

33. You’ll never wake up knowing “today is the day.”

34. Practice doesn’t make perfect; perfect practice makes perfect.

35. If you can’t tie a trustworthy knot, change a tire, kill your own food or perform basic first-aid procedures, you are not really prepared.

36. There is no one-weapon system, tactic, technique or school of thought to address every situation. Those who believe such claims are positively delusional.

37. Murder is wrong, while killing is sometimes necessary and excusable. Make sure you are okay with this idea. If not, you shouldn’t carry a weapon.

38. You are personally responsible for the right to keep and bear arms. Take this responsibility seriously or the gun magazines of the future might be pretty dull —“Cover story: A bar of soap in a sock — the ultimate manstopper!”

39. There is always “one more” — one more gun, one more problem, one more knife, one more bad guy.

40. Our opponents are frequently smarter than we give them credit.

41. A bad outcome in the legal system after a justified use of force can be just as devastating as a major gunshot wound. Know your legal rights and responsibilities.

42. Never get between two people fighting.

43. Train yourself to relax during and after stressful events. You’ll perform better and even live much longer.

44. Go somewhere inspiring and meditate on the concept of “honor.” Do this regularly and you are less likely to do something cowardly or immoral.

45. Guns and alcohol don’t mix. If you drink, you must be unarmed. If you can’t live by the rule, don’t drink. This rule personally chafes me, but I follow it religiously.

46. Never stand in a doorway.

47. Use light to your advantage. Whenever possible, just flick light switches rather than using a flashlight. Then again, if you aren’t proficient with flashlight shooting techniques, you are at a disadvantage in many dangerous encounters.

48. Always carry a knife, a gun and a light. Two is better, but one is critical.

49. “Preparedness” or “being tactical” should be an unspoken lifestyle, not a publicly shared hobby.

50. Buy a three-year subscription to GUNS for every one of your friends, family members, acquaintances and random homeless people on the street. You’ll end up richer, thinner, have more friends and be gloriously rewarded in the afterlife, or my name isn’t Hilary Clinton.