The Boy’s of ’76Seventh Cavalry Letters and Recollections

The men who served in the Seventh Cavalry in 1876 came from all walks of life. Some used the army for their own means; men who were one step ahead of the law. Others yearned for the excitement and adventure that the frontier army could provide.

The men who served in the Seventh Cavalry in 1876 came from all walks of life. Some used the army for their own means; men who were one step ahead of the law. Others yearned for the excitement and adventure that the frontier army could provide.

Forty-two percent of the Seventh Cavalry ranks were foreign-born, with Irish and Germans predominating. Ironically, many western Europeans fled to the United States to escape military conscription. The army offered hope and a unique opportunity to learn English, to read and write, and learn the customs of their newly adopted country. The isolated life of a soldier could best be described as glittering misery. The caste between officers and enlistedmen was strictly adhered to. Here then, is part of the remarkable and poignant story of the 1876 Sioux War, told in their own words.

Fort A. Lincoln

Mar. 5, 1876

Dear Sister:

. . . we expect to leave here any day now . . . The boys are all making blanket shirts. I had a green blanket and so I made [a shirt]. . . I am going to bring it home when my time is out. We expect to go out after Sitting Bull and his cut throats, and if old Custer gets after him he will give him the fits for all the boys are spoiling for a fight. I only hope they will put it off until about the first of May and then we will not run the risk of freezing to death for its cold weather here now and I had rather be in quarters than out on the prairies in tents. Tell Irwin to write . . . I wish he were out here for awhile I would let him ride Dan Tucker. He is fat as a pig and feels so good he ran away with me yesterday and ran two miles before I could stop him . . . will say goodbye.

Henry

Henry Allen Bailey, a Blacksmith in Company I, was and killed with the Custer Battalion 25 June 1876 during the Battle of the Little Big Horn. Born in Foster, Rhode Island, his previous occupation was blacksmith. He enlisted on October 24, 1872 at the age of 22 in Springfield, Massachusetts. He had gray eyes, fair complexion, brown hair, and was 5’7 1/4” tall.

Ft. Totten, D.T.

March 5th, 1876

Dear Sister:

I take the preseant [sic] oppertunity [sic] of letting you no [sic] that I will soon be on the move again. We are to start the 10th of this month for the Big Horn country. The Indians are getting bad again. I think that we will have some hard times this summer. The old chief Sitting Bull says he will not make peace with the whites as long as he has a man to fight. The weather very cold hear [sic] at preasent [sic] and very likely to stay so for two months yet.Ella, you need not rite [sic] me again until you hear from me again. Give my love to Sister & Brother Jonny. Remember me to your husband. As soon as I got back of the campaign I will write you. That is if I do not get my hair lifted by some Indian. Well I will close, so no more at preasant [sic],

From your loving brother,

T.P. Eagan

P.S.

If you hear from Hubert tell him not to write until he hears from me.

Thomas P. Eagan was a Corporal in Company E and killed with the Custer Battalion during the Battle of the Little Big Horn June 25, 1876. His previous occupation was laborer. He enlisted on September 12, 1873, at the age of 25 at St. Louis Barracks, Missouri. He had gray eyes, light complexion, and was 5’5 1/2” tall.

William C. Slaper shared an interesting and humorous account of his experience as a young cavalry recruit enroute from Jefferson Barracks Missouri to Ft. Abraham Lincoln, Dakota Territory aboard a Northern Pacific Railroad car:

Jamestown, D.T.

March 25th, 1876

Ft. A. Lincoln. D.T.

April 20th 1876

“While stopping for coffee and something to eat at Fargo, Dakota, we had about two hours to wait. An Irish sergeant in charge of our car—seemingly an old veteran—instructed a bunch of recruits to go to a certain saloon not far from the station, take their canteens and guns, and pawn or trade the weapons for liquor, and to bring the liquor back in their canteens. On our return with the whiskey, he then took a squad of recruits, armed them as guards, and marched them over to the saloon. Here he threatened the proprietor for buying government arms and immediately confiscated the pawned weapons!. . . from Fargo to Bismarck that night, the sergeant’s car contained a bunch of noisy and hilarious troopers.”

William C. Slaper was a private in Company M and took part in the valley fight and subsequent two day battle on Reno Hill, and survived the Battle of the Little Big Horn. He was born in Cincinnati, Ohio and enlisted on September 10, 1875 in Cincinnati. His previous occupation was safemaker. He had blue eyes, brown hair, fair complexion, and was 5’8 1/2” tall. After the battle he was appointed corporal and received an honorable discharge on expiration of service on September 9, 1880 at Ft. Meade, D.T. as a corporal of good character. He died November 13, 1931.

The following is a vivid twentieth-century account by German immigrant Charles A. Windolph describing the departure of the Dakota Column from Ft. Abraham Lincoln, May 17, 1876:

“The wagon train was headed west, the wheels of the heavy outfits making big ruts in the rain soaked ground. General Terry suggested that Custer parade to the fort so that the worried women and children there could see for themselves what a strong fighting force it was. The band on white horses led off and we paraded around the inner area. Then married men and officers were allowed to leave their troops and say good-by to their families. In a few minutes ‘Boots and Saddles’ was sounded, and the troopers returned to their companions. Then the regiment, its guidons snapping in the morning breeze, marched off, while the band played over and over again ‘The Girl I Left Behind Me’ . . . You felt like you were somebody when you were on a good horse, with a carbine dangling from its small leather ring socket on your McClelland [sic] saddle, and a Colt army revolver strapped on your hip; and a hundred rounds of ammunition in your web belt and in your saddle pockets. You were a cavalryman of the Seventh regiment. You were a part of a proud outfit that had a fighting reputation, and you were ready for a fight or a frolic.”

Charles A. Windolph, aka Charles Wrangel, a German immigrant, was a private in Company H, and a recipient of the Medal of Honor at the Battle of the Little Big Horn with the citation: “With three comrades, during the entire engagement, courageously held a position that secured water for the command.” He was promoted to corporal on September 1, 1876. He had brown eyes, brown hair, dark complexion, and was 5’ 6” tall. He was the last surviving Seventh Cavalryman from the battle when he died at the age of 98 on March 11, 1950 in Lead, South Dakota.

Camp Powder River

June 8, 1876

My Dear Wife,

I received your letter today and was glad to hear from you and them little children. I was a great deal troubled about it, that I didn’t get no letter from you. I am all right if I only know that you and them children are all well. We are 250 miles from Lincoln on the Powder River but we don’t see a sign of an Indian but we expecting every day to meet with them. We had terrible bad weather and a terrible snow storm the first and second June.

The Command is stopping here on Powder River and resting two days. We are going to leave here in the morning 5 o’clock for the Yellowstone. The ration [sic] are running out very near, and so we have to hurry to get to the Yellowstone. Myself and Hageman and Weis got some antelopes[sic] meat from them Indian Scouts, but had to pay $2 for a quarter of it. I spended [sic] already $8 for eating. General Tarry [sic] said if we get Sitting Bull and his tribe soon, then we are going home, but if we don’t, we will stay three months and hunt for him. I wish for mine part we would meet him tomorrow. Serg Botzer and me came to the conclusion, it is better anyhow to be home and baking flapjacks, when we get home we will pay up for this and bake flapjacks all the time.

Dear Lizze I cannot forget Harry. I don’t know how it is but he is in my min [sic] all the time, and sometime I worry a great deal about him. The best thing for you to do is to go to the carpenter and get him to make a fraling fenz rows (German) and don’t forget to send for that tombstone, for we don’t know [sic] if we got any time to spare after we get back again.

Take good care of yourself and Hetty and Charly and don’t forget Your Husband And wrighth [sic] to me when [sic] ever you get a change, [sic] for I am lonely her [sic] to hear from You.

Serg Botzer, Hagemann, Weis, Serg Fortny, others and very near the hole [sic] Camp Send their best regards to You and Hetty and Charly. I for myself send my love And a Kiss to You and one to Hetty and Charly. My best Regards to Mrs. Hughes And her Children and to Klein and Mrs Klein and Mrs James and to Serg Loyd, Lawler and Luther.

I remain Your True and Loving Husband.

Henry C. Dose

Trumpeter Troop G 7 Cavalry.

Henry C. Dose, a Trumpeter in Company G, was killed with the Custer Battalion June 25, 1876 during the Battle of the Little Big Horn. Born in Holstein, Germany, his previous occupation was artificer. He enlisted for the second time on February 1, 1875 at age 25 in Shreveport, LA. He had gray eyes, brown hair, fair complexion, and was 5’6” tall. He left a widow Elizabeth, and his two children Hattie and Charles.

No Date: probably early July 1876, Mouth of the Big Horn River.

“When the Red devils got Custer they cut the heart out of this Regiment. It is not often a soldier wastes tears over an Officer But I saw maney [sic] an old hand wipe his blouse sleeve (we had no handerchiefs) [sic] The day we bureyed [sic] Custer. “

D.E.Dawsey

Troop D 7th Cav.

Custer’s last letter to Libbie:

June 22, 1876

Camp at Junction of Yellowstone and Rosebud Rivers

My Darling – I have but a few moments to write as we start at twelve, and I have my hands full of preparations for the scout. Do not be anxious about me. You would be pleased how closely I obey your instructions about keeping with the column. I hope to have a good report to send you by the next mail. A success will start us all toward Lincoln.

I send you an extract from Genl, Terry’s official order, knowing how keenly you appreciate words of commendation and confidence in your dear Bo: “It is of course impossible to give you any definite instructions in regard to this movement, and, were it not impossible to do so, the Department Commander places too much confidence in your zeal, energy and ability to impose on you precise orders which might hamper your action when nearly in contact with the enemy.”

Your devoted boy Autie.

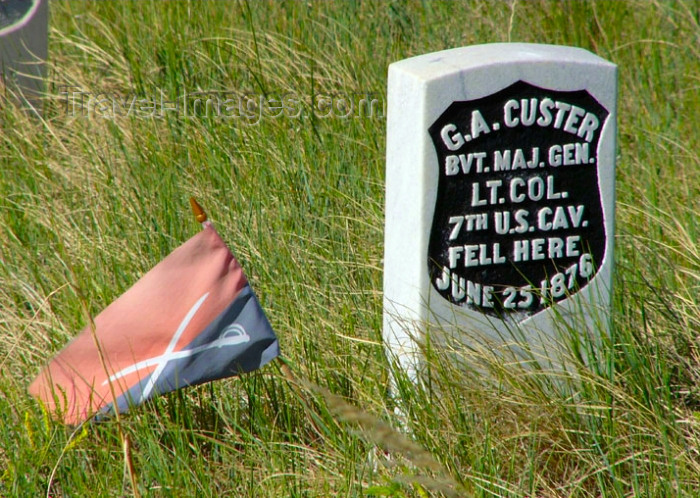

This was the last letter written by Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer to his wife Elizabeth in his “A” tent from the Seventh Cavalry Headquarters bivouac just below the mouth of Rosebud Creek, on the Yellowstone River. Shortly after he finished the letter, Autie, dressed in his familiar buckskins, dark blue shirt, high topped cavalry boots, canvas cartridge belt, holstered pair of Webley R.I.C. white handled revolvers and his familiar white wide brimmed low crowned hat, rode into history and legend at the head of his regiment, marching up Rosebud Creek to the Little Big Horn. Mrs. Custer received the letter after she heard the news of her husbands fate back at Ft. Lincoln. She kept it sealed until she finally gained the courage to read his last words to her.

This last personal recollection is by William O. Taylor who vividly recalled the Seventh Cavalry’s last camp on Rosebud Creek on Saturday June 24, 1876:

Orange Mass.

May 29th 1910

“Our Last Camp on the Rosebud”

It was about sundown on the 24th of June and we had marched nearly Thirty miles along the river following a trail that seemed to grow larger and fresher as we advanced. Emerging from a heavy growth of timber into an opening the command went into camp in one of the most beautiful spots that we had yet seen. On our right rose a high and for a short distance almost perpendicular Bluff. Between that and the river some two or three hundred [sic] away, were great masses of Wild Rose bushes in full bloom, with here and there a tree to add to the park like effect. It was easy to see how the river came by its name, Rosebud, fringed as it was with fragrent [sic] Rose bushes and low willows; it was just such a place for a camp that Custer was in the habit of selecting, when possible, a spot of great beauty, It has ever seemed to me most fitting that what was to be the last camp for so many should be such a beautiful place.

The horses having been fed and rubbed down the men prepared their frugal supper, a cup of hot coffee and a few hardtack, the fires were then put out and most of the men spreading down their piece of Shelter tent and Blanket a few yards in rear of their horses, lay down as they supposed for a nights rest. My troop was quite near to Custer’s Headquarters which consisted of a single A tent close up to the high bluff and facing the river. Before the tent he sat for a long time alone, and apparently in deep thought. I was lying on my side a short distance away, facing him. Was it my fancy, or the gathering twglight, [sic] that made me think that he looked very sad, an expression I had never seen on his face before, were his thoughts far away, back to Fort Lincoln where he had left a most beloved wife, and was he feeling a premonition of what was to happen the morrow.”

William Othneil Taylor was a private in Company A and survived the Battle of the Little Big Horn. Born in Canandaigua, New York his previous occupation was cutler. He enlisted on January 17, 1872 at age 21 in Troy, New York. He had hazel eyes, brown hair, fair complexion, and was 5’5 3/4” tall. Discharged upon expiration of service on January 17, 1877 at Ft. Rice, D.T. as a soldier of poor character.

The “Boy’s of ‘76” left a lasting legacy on the history of America’s westward expansion helping to shape the American experience. Little appreciated by their fellow countrymen—underpaid, under-trained, and often ill equipped—they proudly followed the guidon, enforcing the policies of the United States, and soon faded into history. Today, 125 years later, they continue to capture our imagination. They will forever ride into both history and legend behind their colorful commander, Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer; onward to the Little Big Horn in Garry Owen and glory.

JOHN A. DOERNER is chief historian at the Little Big Horn Battlefield National Monument.

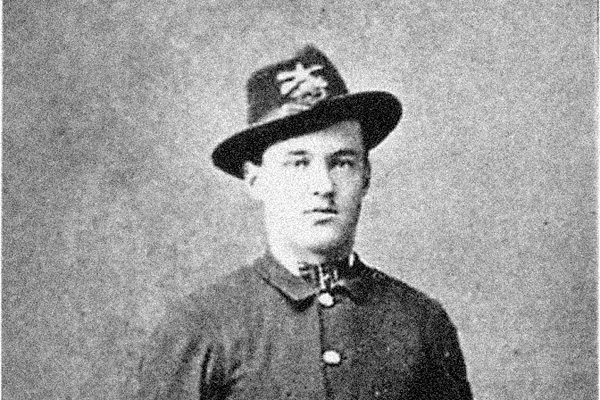

Photo Gallery

– Author’s Collection –

– Author’s Collection –

– Author’s Collection –

– Author’s Collection –

– Author’s Collection –