Truth told, the .38 Special and 9mm aren’t a world away. Put your pitchforks away and quit lighting your torches, the implication isn’t the time-tested cartridges are carbon copies of each other. Not by a long shot. Their countries of origin are disparate, there’s plenty that separates them ballistically and, even as most novice shooters know, they are generally shot from much different handguns.

That said, if you sit down and rattle off the .38 Special and 9mm’s virtues, you’ll end up with nearly identical lists. To start, both are relatively versatile for medium-bore handgun cartridges. Shot out of the right gun, they’re accurate and mild recoiling. Both have more than proven their worth as self-defense options. And each is economical, plentiful and just plain fun to shoot.

From that perspective, they almost seem echoes of each other, maybe even a bit redundant. So, everything laid bare, does it really matter who comes out on top in .38 Special vs 9mm?

Like so many aspects of the gun world, the answer isn’t as clear-cut as picking one or the other. Both are proven and excel at similar applications. But as is so often the case, each shines a bit more than the other for certain shooters.

For a rather notorious cartridge, the .38 Long Colt had a particularly large influence on firearms and ammunition development. Its poor showing in the 1899-1911 Moro Rebellion not only led to the eventual adoption of the .45 ACP and Colt 1911 by the U.S. Military, but also spurred the development of what would become one of the most prolific cartridges of the 20th Century – the .38 Special.

Starting life in 1899 as a black powder cartridge, the .38 Special was essentially an elongated .38 Long Colt that offered greater case capacity. In turn, the .38 Special generated greater velocities as well as shot heavier bullets, which added up to greater penetration potential – an asset sorely lacking in the .38 Long Colt. Proving extremely popular shot from the Smith & Wesson K-frame Military & Police revolver, the cartridge was soon switched over to the modern marvel of the day – smokeless powder.

Given the respectable velocities for its day and the fact it was a kitten to shoot, the .38 Special became the primary service revolver caliber of most American law-enforcement agencies over the decades. Early on, the typical defensive load was a 158-grain lead semi-wadcutter hollowpoint, though later a 200-grain soft-cast lead round nose “Super Police” load become common, offering officers a bullet that yawed upon impact and created a larger wound canal.

Generally pushing bullets around 700 to 1,000 fps, the cartridge was quickly overshadowed by magnum and high-pressure semi-automatic pistol cartridges. Furthermore, almost exclusively a revolver round (yes, there are a few exceptions), the 5- and 6-round guns chambered for it paled in capacity to the double-stack pistols that started to dominate in the last quarter of the century.

The cartridge’s saving grace was the concealed carry movement of the past few decades. Double-action revolvers are among the easiest and most reliable handguns around – simply aim, pull the trigger and they go bang. This sort of dependability appealed to some armed citizen, particularly those who didn’t wish to master a semi-auto’s more complex manual of arms. Furthermore, material advancements shrunk down .38 revolvers to the point they became some of the easiest handguns to carry.

Think the polymer-framed Ruger LCR or aluminum-framed Smith & Wesson Model 642. Next to nothing weight-wise, the revolvers not only became a staple for those seeking the utmost convenience, but were light enough they gained popularity as insurance-policy backup guns.

There’s little arguing, the .38 Special is a bit of a throwback to a different era of handgun cartridges, but its usefulness has far from run its course.

In 1901, you would have gotten some funny looks had you claimed this little German cartridge would become among the most consequential ammo advancements of the last 100 years. Going further and maintain it would be among the most utilized centerfire cartridges of all time, heck they might have shipped you off to a nice comfortable rubber room.

Georg Luger’s upstart flew in the face of most conventional wisdom of the time – the 9mm wasn’t a revolver cartridge and it wasn’t big bore. Yet, it succeed and for an important reason — it was designed for semi-automatic pistols and came at a watershed moment when the advancement in handguns got its footing. Not to mention, the 9mm offered plenty of advantages in the breakthrough system.

Going down the list, the 9mm ticks off almost every box of desirable pistol cartridge traits. It was accurate and easy to shoot. It was possible to chamber small pistols for the cartridge. And, perhaps most importantly, it offered the potential firepower once only dreamed about when it came to handguns. There’s plenty of peace of mind in 15-plus rounds, standard capacity of most double-stack 9mms today.

Given it was designed to use smokeless powered, from the start the 9mm operated under much higher pressures than the .38 Speical and generated greater velocities. The maximum pressure for standard loads today is 35,000 psi. And, depending on the bullet weight (it shoots between 115 and 147 grain), generally the cartridge generated somewhere around 1,000 to 1,300 fps of velocity at the muzzle.

Lively, the cartridge for the most part not only meets FBI penetration standards, but it also works well with most jacketed hollow point bullets, ensuring the projectiles reached their maximum expansion diameter. This is particularly true with the new generation of bullets engineered for controlled expansion.

Over the years, militaries and law enforcement recognized these advantages and have flocked to the 9mm. Accordingly, the “Nine” has also become a favorite of armed citizens, who seek not only the assets of the cartridge, but also the guns chambered for it.

Perhaps no other cartridge more options to send it flying. In turn, especially from a defensive standpoint, you’re likely to find exactly the gun to meet your needs — be it a pistol to maximize your capacity or on one to cut down your carry profile.

There’s an old misconception the .38 Special ideal for novices. That is, given the simplicity with which a double-action revolver operates, the tame cartridge makes it perfect for new shooters learning the ropes. In a sense, this is true, if you’re talking about a 4-inch barreled revolver and up. Not so much when discussing many of the popular carry models.

Take the Ruger LCR, for instance. At 13.5 ounces, the ultra-light revolver’s recoil can prove quite stout, generating a bit more than 7 ft/lbs of recoil energy when shooting Hornady’s 125-grain American Gunner ammo. This is nearly twice the amount from say a 4.2-inch barreled Ruger GP101. With the latter, of course, you have a much larger gun you have to contend with, a drawback for concealment. If it’s a plinker or competition gun, this might not matter a lick.

To be fair, you have to deal with the same physics with micro 9mm pistols. The Ruger LC9s generates around 8 ft/lbs of recoil energy spitting out Hornady’s 124-grain Custom ammo.

But, this can become considerably more bearable given the pistol offers the 9mm’s superior ballistics (it’s 210 fps faster than the .38 load), capacity (three more rounds) and concealment. Admittedly, there are hairs to split on the last point, but generally, semi-autos offer a much slimmer profile than revolvers, making them easier to keep under wraps.

OK, so what? You’ll get used to the recoil, what you care about reliability. Good point, on average a .38 Special revolver will experience fewer malfunctions than a 9mm pistol. Yet, the good ol’ revolver isn’t immune to failures and the argument exists that when a wheelgun fails it’s much more catastrophic than a pistol.

There’s no simple “tap and rack” to solve something like a pulled bullet or a stuck case in a revolver; in many circumstances getting it in working order involves tools – not ideal if your life depends on getting the gun back into the fight.

Overall, it’s difficult to argue that when it comes to concealed carry, for most modern shooters the 9mm edges out the .38 Special. As mentioned before, the semi-auto pistol cartridge offers better ballistics, is chambered in larger-capacity guns, of which there is a greater selection and, for the most part, are easier to conceal. Certainly, semi-auto pistols do require more practice to become competent, given the greater odds of having to solve a malfunction. Though, to many, this is a small trade-off.

With that said, the .38 Special is no slouch. Over the years, it has more than proven itself a capable self-defense cartridge and in recent times has benefited from the advancements in ammunition. In the right hands and with the proper round, there’s no reason to believe the tried-and-true revolver cartridge won’t perform admirably in a self-defense situation.

Additionally, a streamlined manual of arms, mastering most of the guns chambered for it is generally a simpler task. While it may not be most people’s first choice any longer, it is no less a valid choice overall.

Stepping away from defensive applications, the one area the .38 Special perhaps has an edge on the 9mm beat is versatility, particularly on two fronts: guns and reloading. To the former, since it is the parent of the .357 Magnum, it is possible to shoot the .38 in nearly any gun chambered for the larger cartridge.

This is a benefit from the standpoint that it is normally less expensive per round than the magnum and a magnitude less punishing to shoot. To the latter, given it has more case to work with the .38 also has more potential on the reloading bench. With experience and understanding about its capabilities, a handloader can get a lot out of the cartridge.

The .38 Special won’t break the bank by any stretch of the imagination. At the same tick, it still won’t outdo the 9mm for economy. Outside of the .22 LR, there is perhaps no more cost-effective option out there – especially when talking centerfire cartridges.

A quick survey of LuckyGunner.com gives a good example. At their cheapest, the .38 Special comes in at around .25 cents per round, the 9mm .14 cents – roughly a whole three more rounds per dollar spent. Over a long afternoon shooting that adds up.

There is no doubt modern shooters have embraced the 9mm and for good reason. Of nearly all handgun cartridges on the market today, it is among the most well-rounded and allows even new shooters the ability to become proficient. Furthermore, dominating the gun world as it has, the 9mm just plain has more options when it comes to firearms.

You’re more likely to find a gun to fit exactly what you need, be it a service-pistol for your nightstand or a single stack for your belt holster. Finally, given ammunition advancements, it will perform in the direst circumstances.

Nevertheless, the .38 Special is still around for more than just the sake of nostalgia. While overall it doesn’t offer all the advantages of the 9mm, it remains a very competent cartridge, one of which many still trust their lives.

Arguably, the cartridge takes a bit more research to find the optimal defensive round, but for those who desire the reliability of a revolver that’s a small hurdle.

But what the poll found is that they have a lot of work to do when it comes to those 38 and younger. Just one example: Four in 10 say it is OK to burn the flag.

“Younger Americans (under 38 – Gen Z and Millennials) are becoming unmoored from the institutions, knowledge, and spirit traditionally associated with American patriotism,” the survey analysis said.

The highlights provided to Secrets:

On the release of the report, Nick Adams, founder of FLAG, said, “We suspected that we would find decreasing numbers of Americans well-versed in our nation’s most important principles and young people less patriotic than the generations that came before, but we were totally unprepared for what our national survey reveals: an epidemic of anti-Americanism.”

He added, “That half of millennials and Gen Z believe that the country in which they live is both ‘racist’ and ‘sexist’ shows that we have a major fraction of an entire generation that has been indoctrinated by teachers starting in grade school that America is what’s wrong with the world.”

———————————————– The Older Generation always says this about the younger one. But then as History proves. The Youngsters ALWAYS proves them wrong! There is nothing wrong with the Millennial’s!

They just need some guidance & Leadership and they will be just fine. Grumpy

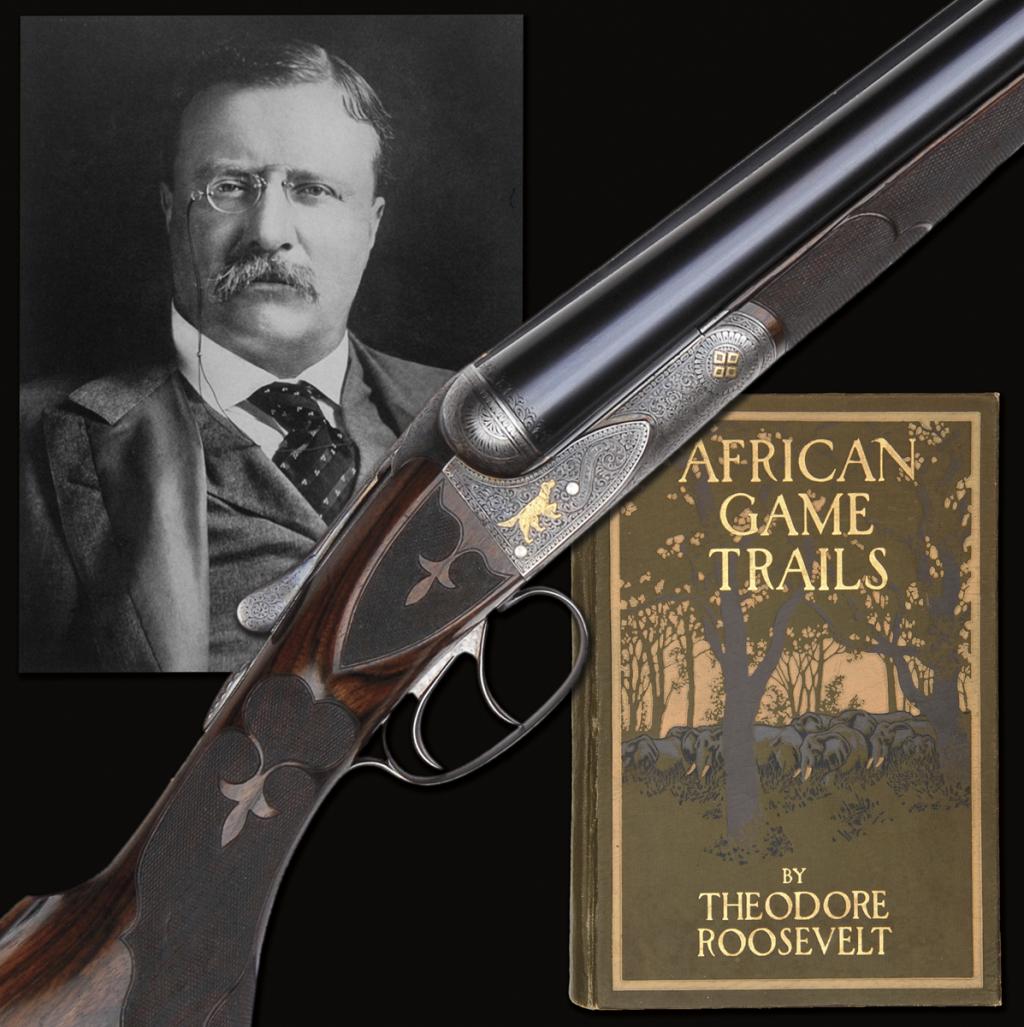

I got my Son one of these back when he was still in High School. Hopefully some day we can finally put it thru its paces!

This is a list of submachine guns.

It includes assault rifles chambered for submachine gun or pistol cartridges, machine pistols, and personal defense weapons (PDWs), all of which are sometimes designated as submachine guns.

Below is the list of submachine guns.

October 30, 2013 – Photo by Staff Sgt.Tim Chacon

“…the expectations of a Major are very different than those of a captain, and not everyone knows what these expectations are or the impact they have on personal and professional success.”

-MG(R) Tony Cucolo, “In Case You Didn’t Know It, Things Are Very Different Now: Part 1”

While attending the Command and General Staff College (CGSC), instructors and mentors constantly drove two points home. First, transitioning to the rank of Major and the expectations of a Field Grade Officer is a difficult and steep learning curve. Second, what made an officer successful at the company grade level does not necessarily translate to success as a Major.

I have been a combined arms battalion S3 for ten months now and during this period I’ve planned, resourced, and executed field training exercises, live fire events, gunneries, an NTC rotation, and spent enough hours on my Blackberry that I never want to see one again.

However, I can definitively say two things about my instructors’ advice: They weren’t kidding about either point … and they vastly downplayed both.

The transition to Major is less of a learning curve and more of a sheer cliff. There is less tolerance for officers who need to “grow into it,” and the expectation is you are value added on day one.

Finally, the room for mistakes grows smaller and smaller. What follows are the hard lessons I’ve learned either through personal shortcomings or watching peers fall by the wayside.

Failure #1: Believe Help is Coming

When things became supremely difficult or complex as a captain or lieutenant, we would often look for a field grade to give refined guidance and direction. The Major knows the answer.

They are the responsible adult in the room. The Major may get cranky and hand out a butt chewing, but they would bring resources to bear on the problem. They were help when we needed it.

As a Major, YOU are now that responsible adult who has the answers and can bring resources to bear. You ARE the help that’s coming.

There is no help coming for YOU. Majors are the Army’s problem solvers and workhorses. If a room of Majors looks around and cannot tell who among them is lead on an issue, then the issue is probably not being addressed.

Majors don’t get to look around and wonder who will solve the problem. They must own the problems as they appear and work with peers to solve them.

Failure #2: Burn Bridges and Fail to Cultivate and Maintain Relationships

Early on in my time as a BN S3 something went wrong during our FTX. A situation changed that was outside of my control and I blamed the brigade.

Over the phone, I got into a heated discussion with the BDE S3 and XO and lost my temper and composure.

When I was done venting, the BDE S3 said something I will never forget: “Do you want to keep complaining or do you want to solve the problem?” Those words stuck with me. I apologized, we moved on, and we fixed the issue.

The argumentative Major, the one who picks fights, protects their own rice bowl, and never gives an inch will quickly find themselves isolated without a seat at the table.

In the end, their unit will suffer for it. Conversely, the Major is willing to give more than they take, willing to put the brigade’s success over what’s easier for their battalion and work well with peers to find solutions and compromises will succeed.

Leaders do not have time for personality conflicts, especially Majors.

The biggest power Majors have is that knowing where to look, who to call, and having a network of friends, peers, classmates, warrants, and NCOs that can be leveraged to solve problems.

Most problems in a brigade are solved by the S3s and XOs sitting around the table, developing a course of action, and moving out to attack the challenge at hand.

That requires well-cultivated and maintained relationships. More than anything, those relationships and connections are the most powerful resource at your disposal.

This is also the point in our careers where many of us will begin to regularly interact with DA Civilians. Do not forget about them.

The GS-14 serving as your Division Chief of Training could well be a retired LTC and former Battalion Commander. They have either been where you are now, or they have seen many in your position come and go, and they often serve as the long-term continuity in higher headquarters and support functions that are critical to your success.

Stop by and talk to your peers regularly. Take time to talk to DA Civilian, get away from email, and drop by offices.

Come to meetings early and stay a little after to talk to each other, even if it’s just letting each other vent for five mins. It will pay dividends when you need to move a mountain and get a short notice task done.

You cannot afford to have personality conflicts or fight with your peers. Ever. Period. Learn to swallow your pride and be the first one to apologize or mend a relationship after a heated exchange.

Failure #3: Confusing Leadership and Management

Leadership and management are not the same thing and are easily confused when assuming organizational level leadership for the first time.

Leadership is about people while management is about systems. While these concepts may appear obvious, it took me about three months to learn this and I am still working to improve my management skills.

As a Major, your primary concerns are building and managing systems. Majors are about touch points. Identify critical touch points for your organization, develop systems to manage that information, and use those systems to recognize where the train wrecks and pitfalls are.

The Major’s aperture is so wide that there is no way you can directly affect it all with personal involvement or presence. If you try, you will fail.

Time is now your most precious resource. Systems help manage the information flow so you can focus your limited time on things that are commander priorities, mission-critical, or something only YOU can do based on knowledge, skills, or relationships.

For everything else, develop your staff to handle routine business, empower them to make the routine decisions, and train them to know when things require your personal involvement. If you don’t develop systems to manage the massive amounts of information coming in, you will quickly become overwhelmed and remain in crisis management.

This is not to say that personal leadership is not important as a Major. It simply means the balance has shifted. Your personal leadership is still critical in two areas: training your staff and mentorship.

Do not expect to walk into a staff that can do MDMP perfectly with just an occasional guiding nudge from you. You will have to train your staff.

MDMP is just the beginning. How to write emails, brief the commander, write orders, develop courses of action, work as a team, interact with the higher headquarters staff, Army culture and expectations of officers, and a thousand other things you now take for granted after over a decade of service.

All of this requires your personal presence, time, and effort. If you do not teach them, no one else will.

The Major is also a mentor to younger officers, especially the staff officers they interact with daily. This mentorship requires personal leadership and is just as important to the Army’s success as the next round of MDMP is to your unit’s training event.

I am wearing an oak leaf because of the mentorship two Majors provided at critical junctures in my career. Officers in your organization will look to you as a model for future service: how to act, how to look, and the path they should chart through the Army, just as I looked to those Majors when I was a Lieutenant and a Captain.

Failure #4: Fail to Predict the Future

Majors must forecast out, identify implied tasks, determine conditions that need setting, and execute without guidance, FRAGOs, or WARNOs from BDE or higher.

If you fail to do this, the train wreck is waiting and, remember, no help is coming. Your higher HQ may give some guidance, but never enough, and never on the timeline you want it. If you wait, it will be too late.

Predicting the future allows planning to occur that can mitigate future problems. This is critical because at the battalion and brigade level dynamic re-tasking is never dynamic.

As a BN S3, I can pick up the phone and redirect the work, efforts, and lives of 700 Soldiers, officers, warrant officers, leaders, and their families.

However, a battalion has a certain organizational momentum and inertia that is hard to overcome and shift on a dime. Every dynamic shift exponentially increases the chance of details being missed, mistakes being made, and can push you into crisis management.

Look deep, develop a concept, and address potential gaps through FRAGOs, IPRs, and update briefs as necessary.

As Majors our words, actions, and decisions carry serious weight as BN and BDE S3s/XOs, planners, and action officers.

An errant email, simple misspeak, or a rash outburst will affect entire organizations exponentially more than when we were company commanders or staff captains.

As such, the tolerance for those who fail to grasp this and make the transition is low. Unfortunately, many Majors step into these pitfalls, sometimes irrevocably, without ever knowing they have made a fatal error.

Fortunately, the Army is a learning organization and just maybe sharing my own shortcomings can help another Major avoid failure as they climb the cliff and make the transition.

Terron Wharton is currently serving as the BN S3 for 4-6 IN, 3/1ABCT at Fort Bliss, TX. An Armor Officer, he has served in Armor and Stryker Brigade Combat Teams with operational experience in Iraq and Afghanistan.

He is also the author of “High Risk Soldier: Trauma and Triumph in the Global War on Terror,” a work dealing with overcoming the effects of PTSD. His other works include “Becoming Multilingual”, discussing being multifaceted within the Army profession, “The Overlooked Mentors” which speaks to NCOs as mentors for junior officers, and “Viral Conflict: Proposing the Information Warfighting Function” which proposes establishing an Information Warfighting Function.

Open the action. With a light or reflector — and with the action open and bolt removed if appropriate — look down the bore. Clean, shiny and clear of obstructions, right? If not, let the bargaining begin!

While many rifles will shoot accurately with a slightly pitted bore, some won’t – and all will require more frequent cleaning. Work the action and see if there are any binding spots or if the action is rough. Ask if you can dry fire it to check the safety.

Some people do not like to have any gun in their possession dry-fired; others don’t care. If you cannot, you may have to pass on the deal. Or, you can assure the owner that you will restrain the cocking piece to keep the striker from falling.

Close the action and dry-fire it. How much is the trigger pull? Close the action, push the safety to ON, and pull the trigger. It should stay cocked. Let go of the trigger and push the safety OFF. It should stay cocked.

Now, dry-fire it. Is the trigger pull different than it was before? If the pull is now lighter, the safety is not fully engaging the cocking piece, and you’ll have to have someone work on it to make it safe. If the rifle fires at any time while manipulating the safety (even without your having touched the trigger) it is unsafe until a gunsmith repairs it.

Inspect the action and barrel channel. Is the gap between the barrel and the channel uniform? Or does the forearm bend right or left? Changes in humidity can warp a forearm and, if the wood touches the barrel, alter accuracy. The owner may be selling it because the accuracy has “gone south,” and not know that some simple bedding work can cure it.

Look at the action where it meets the stock. Is the wood/metal edge clean and uniform? Or do you see traces of epoxy bedding compound? Epoxy could mean a bedding job,and it could mean a repair of a cracked stock. Closely inspect the wrist of the stock, right behind the tang. Look for cracks and repairs.

Turn the rifle over and look at the action screws. Are the slots clean, or are they chewed up? Mangled slots indicates a rifle that has been taken apart many times – and at least a few of those times with a poorly-fitting screwdriver.

Remove the bolt if you can. If not, use a reflector or light to illuminate the bore. Is the bore clean and bright? Look at the bore near the muzzle. Do you see jacket fouling or lead deposits? Many an “inaccurate” rifle can be made accurate again simply by cleaning the jacket fouling out of the bore. While looking down the bore, hold the barrel so a vertical or horizontal bar in a window reflects down the bore. If the reflection of the bar has a ‘break’ in it, the barrel is bent. Sight down the outside of the barrel and see if you can spot it. A slightly bent barrel can still be accurate, but will walk its shots when it heats up. A severely bent barrel must be replaced.

Editor’s Note: This article is an excerpt of our new book Gun Digest Book of Modern Gun Values, 18th Edition.

Freshly updated Gun Digest Book of Modern Gun Values, 18th Edition is the guide for the contemporary gun enthusiast. Focusing on the most frequently bought and sold firearms from the past 100 years, the book is a must for shooters looking to navigate today’s crowded gun market with the utmost confidence. Get Your Copy Now