Striker fired pistols are easier to teach to new shooters, easier to make acceptable hits with, have increased capacity, and generally cost less.

This article is not to convince you that the revolver is superior to the striker fired pistol, although it does have its advantages.

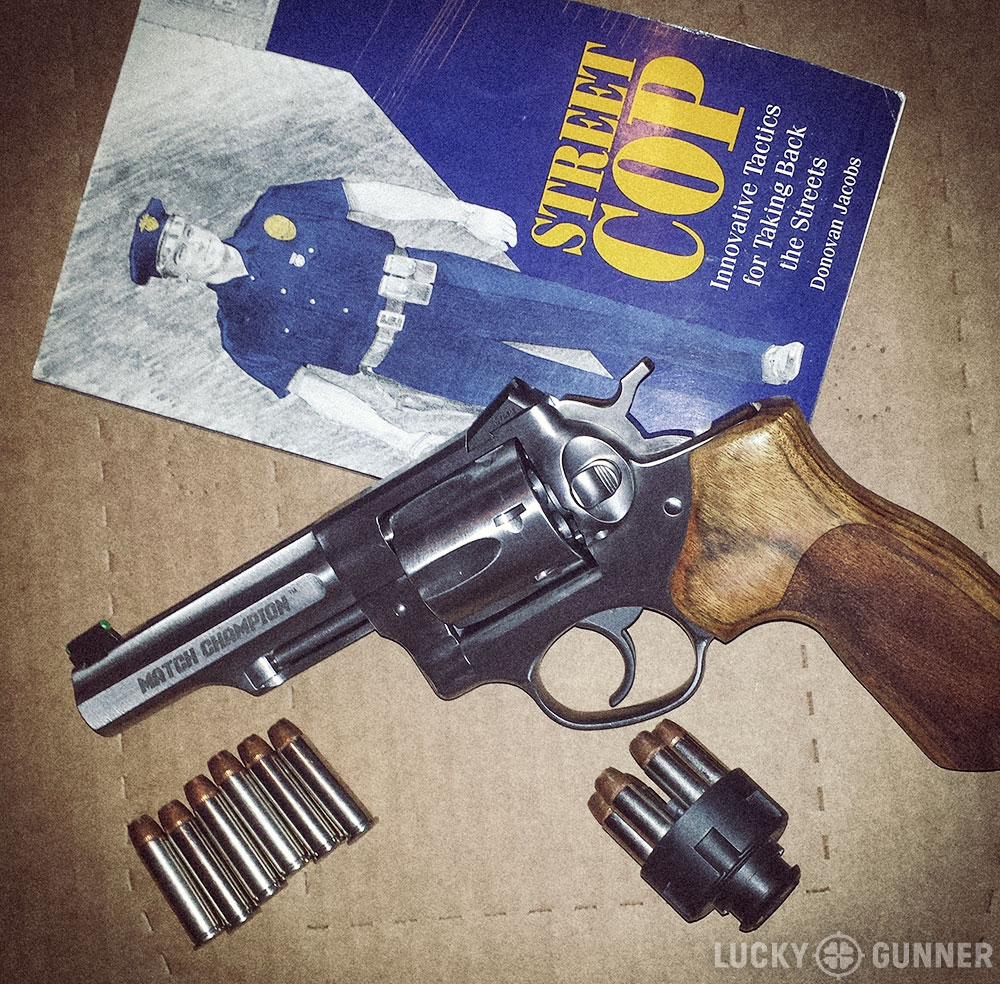

I hope to make the case that the old school workhorse, particularly the Ruger GP100 Match Champion with a few modern touches, remains a viable option for those who carry a firearm to protect themselves and others.

Chris has also spent some time evaluating the GP100 Match Champion since using it as one of the test guns for the Lucky Gunner ballistic gelatin tests. Here is a quick overview video with some of his thoughts followed by the rest of my review

Before delving into specifics, let’s establish a standard for what makes a good duty gun.

It needs to be easy to shoot, and even more importantly, it needs to be easy to not shoot.

Accidentally shooting yourself or someone else is obviously unacceptable, and, while skill level under stress is key to preventing accidental or negligent discharges, hardware selection can mitigate the risk occurring.

The gun must be acceptably accurate, and while that particular nit can be picked endlessly, let’s say it’s like pornography and I know it when I see it.

It must be rugged enough to withstand daily carry, which includes exposure to sweat, weather, and the occasional bump or scrape.

It must have available support gear, such as holsters and speed loaders or magazines.

It must be controllable by the individual shooter in two handed shooting, strong hand only, and weak hand only in case of fighting injured.

The GP100 Match Champion

Now that we have established a standard, let’s take a look at a modern double action revolver, the Ruger GP100 Match Champion, and see how it meets those standards.

I bought my Match Champion with fixed Novak style rear sights as soon as it first became available back in 2014.

Since then, Ruger has released an adjustable sight model like the one Chris reviewed above.

Other than the sights (and frame changes to accommodate them), the models are identical.

They are 4.2-inch barreled stainless steel .357 magnum revolvers with textured Hogue wood grips, very similar to the duty revolvers of yesteryear but with some modern updates.

Historically, Ruger is generally regarded as more of a utilitarian revolver maker who makes a sturdy piece at a good price, but fit and finish may not be quite as good as some other makers. The Match Champion fits this stereotype but is more aesthetically pleasing than the standard GP100s and the Security-Six-series the GPs replaced back in the late 1980s.

First, the lawyer/lawsuit rollmark has been moved to a simple “read instruction manual” engraved on the bottom side of the barrel’s underlug. The barrel is slab-sided with “Match Champion” on one side and “Ruger GP100” on the other.

The factory wood Hogue grips are functional, but the fit is a bit sloppy. They leave an unsightly gap at the back of the frame and do not mate well to the rear of the trigger guard. Cosmetics aside, they do fill your hand nicely and the palm swells and stippling help maintain grip and control recoil. However, the Match Champion grip does change the natural presentation angle a bit versus the standard GP100 grips, so if you’ve got a lot of reps in you may need to burn in new muscle memory to avoid pointing low on presentation.

It is a simple matter to change the grips if you don’t like the factory ones. One advantage of the revolver is you do not need to leave room for a magazine in the middle of your fist, giving you greater flexibility in terms of size and angle. Ruger’s compact grip reduces the height by roughly .6 inches, changes the presentation angle to be the same as the standard GP100, and still leaves room for me to get all of my fingers on the grip. I wear an “L” or “XL” glove, for reference. The compacts come with rosewood inserts, but any SP101 insert will fit. Altamont (the OEM provider for Ruger since Lett closed its doors) offers multiple styles of replacements from snakeskin to scrimshaw.

Ruger’s website states they shim the hammer to center it, but mine is certainly not centered. It is noticeably left of center and does drag the frame, which is evident from visible wear on the side of the hammer.

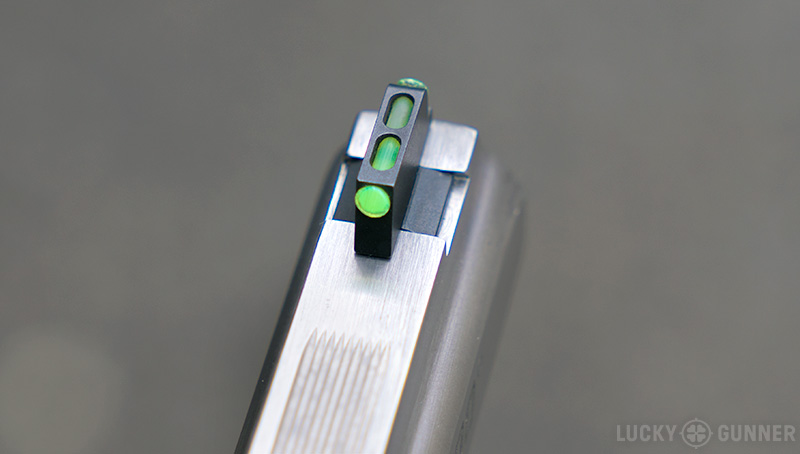

The front sight gathers enough light to use in most lighting conditions, despite the shielding partially covering fiber optic rod (more on that below). I have found it easy to shoot in both daylight and indoors. For the fixed rear sight version of the Match Champion, there is no method to adjust elevation other than adjusting sight picture. Given the wide range of .38 and .357 loads and the effect of the individual’s grip, no fixed sight is going to match up to all ammunition choices.

Even at just seven yards, there was a noticeable difference in point of impact between firing factory PMC Bronze 158 jacketed softpoint and my own hand loaded ammo. That said, even with the reasonably stout PMC ammo and compact grips, using a 1 second metronome, I was able to shoot reasonable groups at 15 yards.

| Ruger GP100 Match Champion Technical Specs | |

|---|---|

| caliber | .357 Magnum |

| capacity | 6 |

| weight | 38 ounces |

| barrel length | 4.2 inches |

| sights | fiber optic front, adjustable or fixed Novak rear |

| action | double action |

| MSRP | $969 |

All of my shooting at the range has been done double action, which is how a fighting revolver should be fired (Chris has more on that topic in this article). I do still like a hammer on a full sized revolver for a few reasons, though. The hammer spur allows me hold the hammer down as I reholster, which lets me feel if it starts to move due to some obstruction pushing the trigger. Old timers “roll check” a revolver after loading, essentially cocking and gently lowering the hammer to rotate the cylinder and verify that it spins freely. Debris under the extractor star or a high primer can cause drag on the cylinder, either locking the gun up or significantly increasing trigger pull.

Speaking of trigger pull, the Match Champion is the nicest out of the box Ruger I’ve come across. Describing a trigger is something like describing a glass of wine, lots of terms that may or may not be understood by the target audience, so I’ll just say it’s nice and smooth. Particularly now with regular dry fire and some 2500 rounds through it, it’s quite smooth and breaks predictably with no significant stacking.

The Match Champion is a capable fighting weapon, and it’s one with soul. It seems a shame to shove such a fine piece of machinery into an industrial chunk of plastic shaped into a holster. Revolvers demand leather, preferably custom and gorgeous. I reached out to a friend of mine, Red Nichols, and asked if he had any input. Lucky for me, Red was just about to expand his line of top quality holsters into the world of revolvers. I got one of the first ones hot off the saddle stitcher: an Avenger style holster with emu leg accents, and it works as good as it looks.

Does It Meet The Standard?

So how does this wheel gun match up to our standards for a duty gun?

Is it easy to shoot? The double action revolver does take more effort to master due to the heavier and longer trigger pull but is readily accomplished by someone willing to put in some time and effort.

Is it easy to not shoot? From my own record keeping of unintentional discharges resulting in injury or death investigated by my office, roughly 1/3 are due to improper clearing of the firearm. The magazine is removed but there is still a round in the chamber, and then the trigger is pressed. Revolvers are significantly less complicated to clear and do not “hide” a cartridge when the majority are removed. They also require a longer trigger pull, reducing the likelihood of an unintentional discharge from a sub-conscious “trigger check” or a partially obstructed holster.

Is it accurate? Off hand, I can shoot sub 2-inch groups at 10 yards. We’ll call that adequate for a duty weapon.

Is it rugged? It’s tough to beat the durability of a big chunk of stainless steel, which is essentially what the Match Champion is. Even Achilles had that heel thing going, though, so tough guys do have weak spots. Arguably, the sights would be the weak spot for the Match Champion. Fiber optic sights are not known for their ruggedness. Ruger has mitigated this by shielding the fiber optic rod to protect it from damage.

The fixed rear sight seems to be pretty tough, but it is drift-adjustable, and a hard hit could potentially push it out of alignment. It’s relatively secure, but not quite as immune to unintentional movement as the old integral rear sights.

Is there adequate support gear? The Match Champion fits standard GP100 holsters, so there are plenty of options there. The dovetails are Novak’s cuts, so sight options exist if you don’t find the factory rear sights to your liking. As previously mentioned, there are many aftermarket grips that fit the GP100, and compatible speedloaders are abundant as well.

Is it controllable? While this depends as much on the shooter as the gun, there is a wide variety of ammunition available, from .38 Special wadcutters to full house magnums. Most everyone should find something they can shoot well.

Do Reloading Speed and Capacity Really Matter?

Now, I can already see the incoming comments about capacity and speed of reloading. I concede these are the revolver’s weak points. However, even in the realm of law enforcement shootings where distances are longer, the shooter is more likely to be fighting back from ambush, and attackers are more likely to have cover. Reloading speed very seldom makes the difference. Let’s take a look at an excerpt from an NYPD analysis of over 6000 officer-involved shootings during the 1970s.

“The average number of shots fired by individual officers in an armed confrontation was between two and three rounds. The two to three rounds per incident remained constant over the years covered by the report. It also substantiates an earlier study by the L.A.P.D. (1967) which found that 2.6 rounds per encounter were discharged. The necessity for rapid reloading to prevent death or serious injury was not a factor in any of the cases examined. In close range encounters, under 15 feet, it was never reported as necessary to continue the action. In 6% of the total cases, the officer reported reloading. These involved cases of pursuit, barricaded persons, and other incidents where the action was prolonged and the distance exceeded the 25-foot death zone.”

Even in modern times, the 2013 NYPD Firearm Discharge Report shows less than 14% of shootings against human adversaries involved more than five shots fired per officer. This number should even be viewed with some suspicion as the total rounds reported fired is not the same as total rounds required to end the conflict. It takes time to decide to stop shooting, just as it does to start shooting. In my own records of local non-LE shootings against unknown assailants (i.e., not domestics or other targeted attacks), five or fewer rounds have resolved 100% of those situations one way or the other. Those who lost were killed or disabled prior to emptying their guns, meaning extra capacity would have been irrelevant as they simply ran out of time before they ran out of ammunition.

When police departments made the switch to semi-autos over revolvers, what they typically saw were round counts increasing slightly and hit rates decreasing slightly. Miami-Dade’s 1986-1994 study showed 35% hit with a revolver, 25% with a semi-auto, despite the mean number of rounds fired being 0.7 higher with the semi-auto. There are a number of hypotheses as to why this was the case, from the psychological need to value each shot more highly because of limited capacity to the inherent accuracy of fixed barrel revolvers. Personally, I believe the reason is that the revolver’s trigger makes you slow down a bit more. Anyone who has investigated shootings will tell you that the shooters who fire more than one shot tend to run the gun like a sewing machine, their cyclical rate going through the roof under stress. They fail to let the sights settle before pulling the trigger again. This is why certain semi-auto pistols attempt to replicate the revolver’s longer and heavier pull, such as Sig’s DAK and H&K’s LEM trigger systems. They are trying to slow you down and actually shoot more accurately.

There are exceptions, of course, where capacity and reloading speed may have made a difference in outcome, but those instances are so rare and unlikely that I feel quite comfortable relying on a safer revolver I can shoot accurately despite less capacity. Making those rounds count when it matters is key.

So, to return to the original question of whether the GP100 Match Champion would be a viable duty weapon — for me, as a plain clothes detective, the answer is yes. The minor cosmetic imperfections do not hamper its capability in the slightest, and with a concealable OWB holster and compact grips, it conceals easily under a suit jacket. I would give serious consideration to changing the sights to include an adjustable rear and tritium front, though. The revolver, and the Match Champion in particular, still remains a capable fighting gun in the right hands.