THE 240-YEAR EVOLUTION OF THE ARMY SIDEARM

The weapons that won a revolution and defended a republic.

In late January of this year, the U.S. Army selected a new pistol to replace the Beretta M9, a gun that’s served the Armed Forces for 30 years.

But like every weapon in the U.S.’s arsenal, the Army pistol has gone through a slow evolution, from slow-loading flintlocks that helped create a country to polymer-framed, semi-automatic pistols used in conflicts around the world today.

The U.S. Army has come along way in 242 years.

The Flintlocks That Made America

America’s very first sidearm was a copy of a British one. Based on the British Model 1760, the Model 1775 was a muzzle-loading, .62-caliber smoothbore flintlock.

The American pistols were made by the Rappahannock Forge in Virginia (pictured above), a key manufacturing base and arsenal for the Continental forces that produced 80,000 muskets during the American Revolution.

Copies of the Model 1775 pistol were later made at Harper’s Ferry. This gun was renamed the Model 1805 and was the weapon choice during the War of 1812.

After the Revolution, Connecticut gunmaker Simeon North won a contract to manufacture a new pistol. Based on French pistols of the period, North’s new weapon was smaller than the earlier 1775 model with a side-mounted ramrod and a fired a larger .72-caliber ball.

In 1813, North received another contract for 20,000 pistols from the U.S. Military. These were to have a full stock, fire a .69-caliber ball and most importantly use interchangeable parts, one of the first contracts to request such a feature.

Having these pistols could sometimes mean the difference between life and death. During the War of 1812 while fighting Tecumseh’s Shawnee warriors, Colonel Richard Johnson was wounded in the arm.

Although the veracity of this account is still debated, one story says that Johnson barely had time to cock his flintlock pistol and shoot Tecumseh, a native leader “of undoubted bravery.” Johnson would capitalize on the episode, launching his career as a politician and becoming the ninth U.S. vice president.

North continued to make pistols, manufacturing the Model 1826 for the Navy. The last U.S. flintlock pistol came in 1836, the same year Samuel Colt patented his revolutionary new revolving pistol. Gunsmith Asa Waters produced the Model 1836 until the early 1840s, a weapon used widely during the Mexican-American War.

For almost a century the flintlock had been the dominant ignition system for firearms, but being susceptible to the elements.

They were too unreliable and by the 1840s many of the major European powers, like Britain and France, began transitioning away from increasingly obsolete flintlock pistols to new percussion-lock pistols.

These new guns used fulminate of mercury percussion caps to ignite the gunpowder instead of a flint. The U.S. used the old flintlock system throughout the 1830s and 40s before slowly transitioning to the new percussion cap revolvers.

The Birth of the Revolver

Formally adopted in 1848, percussion revolvers represented a massive leap forward in firearms technology. It’s most basic improvement was simple math— a soldier now had six shots before reloading rather than only one.

But the firepower of these new pistols was also highly sought after, and revolvers became one of the most iconic weapons of America’s bloodiest conflict.

The U.S.’s first revolver was the Colt Dragoon, initially designed for the Army’s Regiment of Mounted Rifles. The Dragoon improved on the earlier Colt Walker, a gun used heavily during the Mexican-American War. The Dragoon would be the first of a series of Colt pistols used by the U.S. throughout the 19th century.

Then came the Civil War, and a plethora of percussion revolvers were soon found their way into the hands of Union and Confederate soldiers alike.

The Union predominantly issued Colt and Remington revolvers. Approximately 130,000 .44-caliber, Colt Army Model 1860s were purchased along with considerable numbers of Colt 1851 and 1861 Navy revolvers.

Following a fire at Colt’s Connecticut factory in 1864, the Army placed significant orders for Remington Model 1858 pistols to fill the gap.

The solid-frame Remington was arguably a better, more robust pistol than the open-frame Colt revolvers. Remington continually improved the Model 1858 based on suggestions from the U.S. Army Ordnance Department.

For both sides pistols were often a soldier’s last line of defense. One Confederate newspaper reported that a badly wounded captain commanding a battery of artillery at the Battle of Valverde “with revolver in hand, refusing to fly or desert his post… fought to the last and gloriously died the death of a hero.”

On the other side of the frontline, one Union calvaryman recalled:

“I discharged my revolver at arm’s length at a figure in gray and he toppled onto the neck of his mount before being lost in a whirl of dust and fleeing horses… I found that both my pistols were emptied… there were five rebels who would not trouble us anymore and many others who must have taken wounds.”

It was not uncommon for cavalry to carry multiple revolvers, as another Union cavalryman wrote “we were all festooned with revolvers. I carried four Colts, two in my belt and two on my saddle holsters but this was by no means an excess. Some of my compatriots carried six because we were determined in a fight not to be found wanting!”

The industrial might of the North ensured that the Union had an advantage throughout the war, and the Confederacy were forced to use imported pistols from Europe and locally produced copies.

These included Adams, LeMat and Kerr pistols and copies of Colts and other revolvers made by Spiller & Burr and Griswold & Gunnison.

By the end of the Civil War, self-contained metallic cartridges were becoming more and more popular. The late 1860s and early 1870s saw another small arms revolution with percussion pistols giving way to cartridge revolvers like the Smith & Wesson Model 3 and the legendary Colt Single Action Army.

The Gun of the West

In 1870, the military purchased its first metallic cartridge revolvers from Smith & Wesson. The Model 3 was a top-break revolver, meaning the barrel and cylinder could be swung downwards to open the action and allow the user to quickly reload the weapon.

The new metallic cartridges removed the need for loose powder and percussion caps and greatly increased the revolver’s rate of fire with a skilled shooter firing all six-rounds in under five seconds. However, Colt, Smith & Wesson’s principal rival, were not far behind.

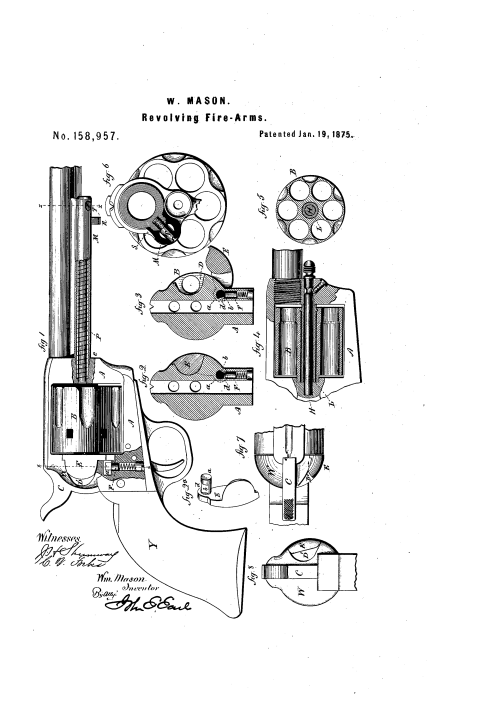

In 1871, Colt introduced their first cartridge revolver, the year after a patent held by Smith & Wesson expired. Colt turned to William Mason, the experienced engineer who had worked on Colt’s earlier pistols.

Mason designed a pistol which outwardly resembled many of Colt’s earlier revolvers, but the new design included a rear loading gate and Mason’s patented extractor rod offset to the side of the barrel, a feature later used in the Single Action Army.

The Colt 1871 “Open Top” was chambered in the popular .44 Henry rimfire cartridge. When the Army tested Colt’s new pistol, they complained that the .44 rimfire round was too weak and that the open-top design wasn’t as robust as rival pistols from Remington and Smith & Wesson. The Army demanded a more powerful cartridge and a stronger solid frame.

Colt quickly obliged producing a run of three sample pistols for testing and examination. This new revolver was the prototype for the now legendary Colt Single Action Army.

The new pistol, developed by William Mason and Charles Brinckerhoff Richards, had a solid frame and fired Colt’s new .45 caliber center-fire cartridge. This gun is still manufactured today.

After successful testing, the Army adopted Colt’s revolver as the Model 1873. The new Colt Single Action Army had a 7.5 inch barrel and weighed 2.5lbs, and an initial order for 8,000 M1873s replaced the Army’s obsolete Colt 1860 Army Percussion revolvers.

The Army also ordered a several thousand Smith & Wesson Model 3s.

These revolvers had a more advanced top-break design and could be loaded much faster than the Colt. For a number of years, the two revolvers served side by side but used different ammunition.

Eventually, the army favored the more robust, accurate, and easier to maintain Colt, and over the next 20 years purchased more that 30,000 of them.

TheColt M1873 Single Action Army would go on to see action in every U.S. military campaign between 1873 and 1905. They were even clutched in the hands of General Custer and his men at the Battle of the Little Bighorn.

Despite its hallowed status, the Single Action Army still wasn’t the apex of handgun technology. While the Single Action Army had excellent stopping power, reliability, and a simple action, it was slow to reload and a slow rate of fire.

To address some of these issues, the Army requested a new double action revolver. The Colt Model 1892 became the first double-action revolver ever issued to the U.S. Army and Navy. Replacing the venerable .45-caliber Colt M1873, the M1892 had a six-chamber cylinder and fired a new .38 Long Colt round.

It had a double-action trigger which improved the pistol’s rate of fire, and unlike the earlier single action Colt, the new revolver chambered, cocked, and fired a round with each pull of the trigger.

Another improvement over the earlier Colt was the M1892’s swing out cylinder, this allowed troops to quickly extract spent cases and reload much faster than the M1873’s hinged loading gate.

While the pistol proved sturdy and reliable in the field, now with a faster rate of fire and easier reload, the Army found that the .38-caliber cartridge lacked the stopping power of the previous .45-caliber Colt.

In 1905, during the Philippine Insurrection a prisoner, Antonio Caspi, attempted to escape and was shot four times at close range with a .38 pistol—he later recovered from his wounds.

Although Colt tried to increase the power of the .38-caliber round, the Army began looking for a new pistol that would chamber the .45 Colt round, and in 1904, the Board of Ordnance began a series of tests to discover what sort of ammunition its next service pistol should use.

The Colt Pistol and a World at War

It would fall to Colonel John T. Thompson (who later designed the iconic Thompson submachine gun) and Major Louis Anatole LaGarde of the Army Medical Corps to investigate the effectiveness of various calibers.

Thompson and LaGarde decided that testing on live cattle and on donated human cadavers would be a suitably scientific method of finding which bullet would put a man down.

The experiments were pseudo-scientific at best and horribly cruel to the animals, especially since they would time how long it would take for them to die.

But finally, the report concluded:

“After mature deliberation, the Board finds that a bullet which will have the shock effect and stopping power at short ranges necessary for a military pistol or revolver should have a caliber not less than .45.”

The Thompson-LaGarde tests were followed by Army trials between 1906 and 1911. The trials tested nine designs, but the competition quickly identified three main contenders. The Savage 1907, designed by Elbert Searle, faced Colt’s John Browning-designed entry and the iconic Luger designed by Georg Luger.

All three pistols were chambered in the new .45 ACP cartridge. In 1908, the Luger withdrew from the trials, leaving only the designs from Colt and Savage.

While both pistols had their problems during the trials, the Savage 1907 pistols were substantially more expensive.

The testing reported a catalogue of issues including a poorly designed ejector, a grip safety which pinched the operator’s hand, broken grip panels, slide stop and magazine catch difficulties, deformed magazines, and a needlessly heavy trigger pull.

During this time, the Colt 1905 Military Model went through a series of changes and design improvements, eventually giving it the edge over its rival. Following final testing on March 3, 1911, the trials board reported: “Of the two pistols, the Board is of the opinion that the Colt is superior, because it is the more reliable, the more enduring, the more easily disassembled, when there are broken parts to be replaced, and the more accurate.”

Colt’s pistol was quickly adopted as the ‘Pistol, Semi-automatic, .45 caliber, Model 1911’.

John Browning’s iconic M1911 used a locked breech, short-recoil action, feeding from a seven round magazine.

It weighed 2.4lbs (1.1kg) unloaded and was just over eight inches long. Ergonomically, its controls were easy to manipulate and included magazine and slide releases and both a manual and grip safety.

The M1911 remained in service for over 70 years and saw action during both World Wars, the Banana Wars, the Korean War, the Vietnam War and the Invasion of Grenada.

Perhaps one of the most famous uses of the M1911 came when Alvin York was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor.

In October 1918, during the battle of Meuse-Argonne, York was charged by a squad of Germans. As they came into pistol range, York drew his M1911 and killed six attackers. That day he single handedly killed a total of 25 German soldiers and captured 132 more.

In 1926, after some lessons learned during World War One, Colt overhauled the M1911 by including a shorter trigger and frame cut-outs behind the trigger, a longer spur on the pistol grip safety, an arched mainspring housing, a wider front sight, and a shortened hammer spur.

Following these changes, the pistol was designated the M1911A1, a weapon that would also fight a world war—just like its predecessor.

A More Modern Weapon

The Colt soldiered on into the 1980s until the U.S. launched the Joint Service Small Arms Program, which aimed to select a new pistol that could be used by all of the armed services.

After a tough competition between designs from Colt, Walther, Smith & Wesson, Steyr, FN, and SIG, a winning design was selected, the Italian Beretta 92. The Beretta formally replaced the M1911A1 in 1986 as the M9.

Even though the military had found its new gun, the 1911 still remains in use by some units such as the U.S. Marine Force Recon Units and Special Operation Command as the refurbished M45, surpassing a century of service.

But the M9 beat out the venerable Colt because it fired the smaller 9x19mm round, which made learning to shoot easier, and it had a much larger magazine holding 15 rounds while using a single-action/double-action trigger. While some complained it lacked the 1911’s .45 ACP stopping power, the M9 served the U.S. military well for over 30 years.

It has seen hard service during the Gulf War, the War in Afghanistan, and the Iraq War.

In March 2003, during Operation Iraqi Freedom Marine Corporal Armand E. McCormick was awarded the Silver Star when he drove his vehicle into an Iraqi position before dismounting and clearing enemy defenses with his M9.

But as technology advanced and new pistol designs emerged, the Army needed a new sidearm to match the times. In the early 2000s, a series of trials led eventually to the Modular Handgun System program.

The Army wanted a lighter, more adaptable pistol which could be fitted to individual soldiers. After several years of testing entries from Glock, Beretta, FN, and Smith & Wesson, the SIG P320 won out.

The new pistol, designated the M17, is lighter, more compact, has a standard 17-round magazine capacity, and is fully ambidextrous. It has a fiberglass-reinforced polymer frame with an integrated Picatinny rail to allow lights and lasers to be mounted, much like the M9’s slide-mounted manual safety.

But the most innovative aspect of the M17 is its modular design. The pistol’s frame holds an easily removable trigger pack, which along with the barrel and slide, can be removed and simply dropped into another frame.

This gives troops in different roles with different requirements some much needed flexibility.

The SIG P320 is completely unrecognizable from M1775, held in the hands of American founding fathers. Much like America itself, the soldiers’ handgun has evolved massively over the last 240 years, but the principle of the sidearm remains the same—the absolute last line of defense.

Wars may not be won with pistols, but a soldier’s sidearm can still be the difference between life and death.