To say that this Officer is controversial would be a huge understatement. In that folks even now over a hundred years after his death at Little Big Horn. They are still talking about him.

His grave at West Point

But enough of that! Since this is a blog about Guns. Here is some stuff I found about his guns. Enjoy! Grumpy

TREASURES FROM OUR WEST: GEORGE ARMSTRONG CUSTER TARGET RIFLE

George Armstrong Custer’s target rifle. 1988.8.735

Originally published in Points West in Fall 2010

Target rifle that belonged to George Armstrong Custer

Although he did not take it with him on the ill-fated sojourn that ended in his death at the Battle of the Little Bighorn on June 25, 1876, this splendid .44 caliber Remington-Rider Long Range Creedmore Target Rifle was owned by Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer. His wife Elizabeth, known affectionately by Custer as “Miss Libbie,” reputedly gave it to him as a gift.

Mrs. Custer presented the rifle to the Winchester Repeating Arms Company in 1883 in memory of her husband, and the Olin Corporation donated it to the Cody Firearms Museum as part of the Winchester Arms Collection.

Remington-Rider Long Range Creedmore target rifle. Gift of Olin Corporation, Winchester Arms Collection. 1988

Military Mystery: What was George Custer’s Last Gun?

by | October 3rd, 201143 Comments

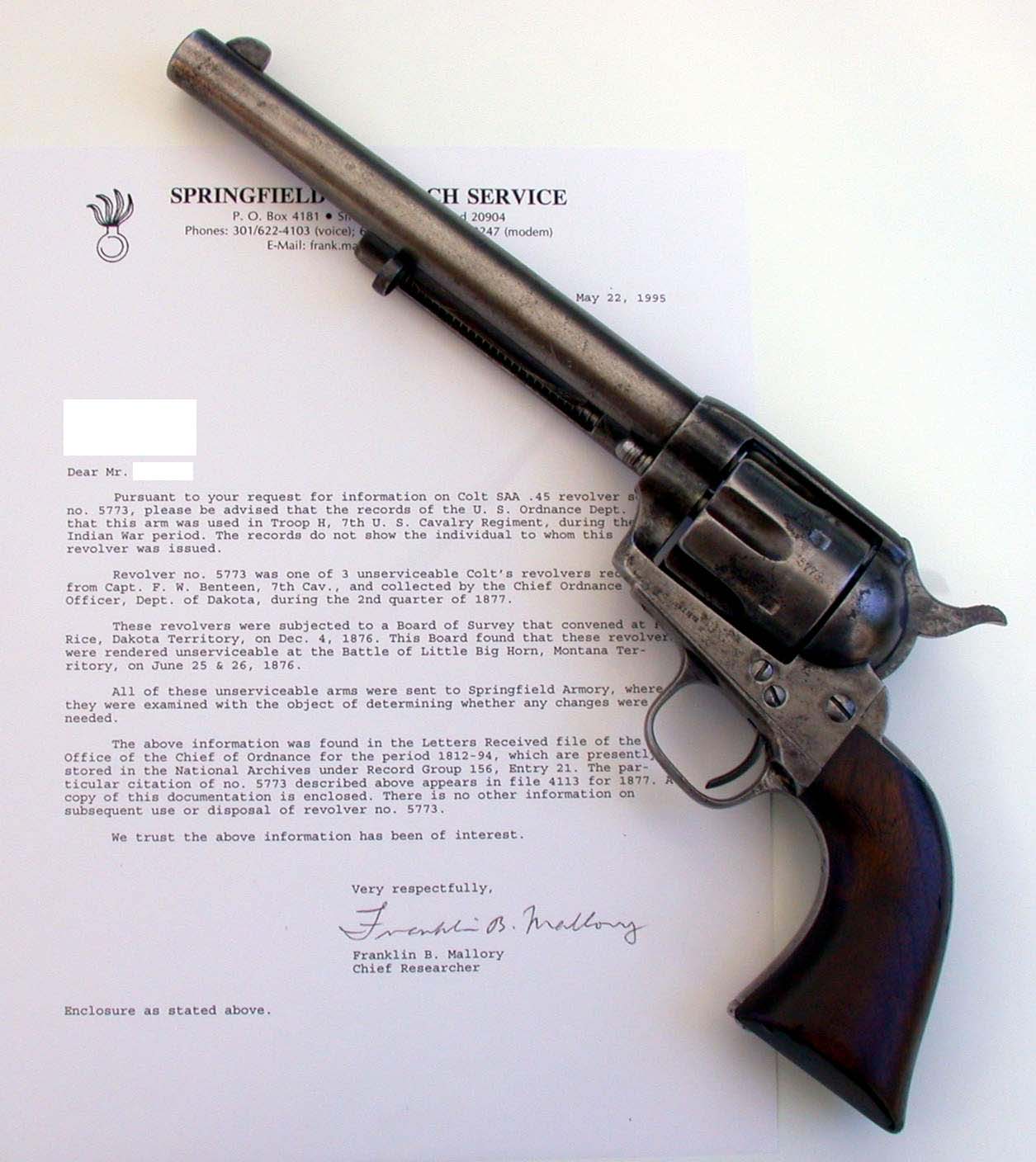

For a good number of years there has been much speculation about what was Lt. Col George Armstrong Custer‘s last gun.

As he and most of his command were killed during the Battle of Little Big Horn, everything has to be put together from spotty evidence, innuendo and guesswork. Here’s my take on the matter.

There is extant, a revealing 1870s-vintage photograph (below) of Custer and his wife, Libby, sitting in their library at Ft. Abraham Lincoln on the Missouri River, Dakota Territory.

In the far right corner is the Lt. Colonel’s gun rack. Four handguns can be seen—two Smith & Wesson No. 2s that had been presented to him by Major General J.B. Sutherland.

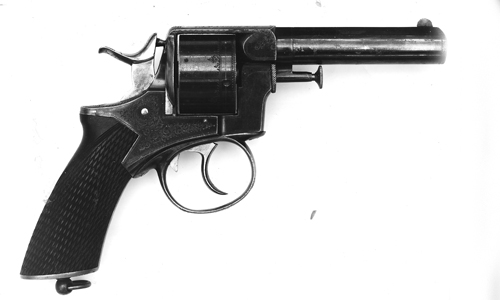

A percussion revolver which is most likely either a Colt 1861 Navy or Remington New Model Army that was given to him by Remington, and what strongly appears to be a Webley Royal Irish Constabulary revolver (pictured above).

One tradition persists that British sportsman Lord Berkeley Paget presented George Custer with a solid-frame Webley First Model Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) revolver on a buffalo hunt in 1869.

The British revolver in Custer’s gun rack follows the lines of the RIC much more closely than those of the Galand, which has a rather involved under-barrel extraction mechanism and slightly different grip than the Webley.

As both Smith & Wessons are displayed and there appear to be empty slots in the rack this supposition would appear to be confirmed. It was very unusual to see double-cased British cartridge revolvers at this period.

Of course there is always another explanation; that being the whole Berkeley Paget thing was something of a red herring and Custer either purchased the Webley himself, or it was given to him by someone else.

Just because a gun was made in England, doesn’t necessarily mean it had to come from an Englishman. British firearms of all types had been actively marketed in the States for decades prior to the 1870s.

The Royal Irish Constabulary revolver, built by Birmingham, England gunmaker Philip Webley, took its name from the force that adopted it in 1868.

This solid-frame double-action at one time or another was chambered in such calibers as .430, .442, .450, .476 and .44-40, among others.

While the military version of the gun had a four-inch barrel, over its long career the gun was also made in short barreled “Bulldog” versions.

“Bulldog” by the way is a British term going back at least to the latter part of the 18th century and along with “barker” and “snapper” was slang for a short-barreled, large caliber pistol.

Due to the date of presentation and/or the Ft. Lincoln photograph, there can be little doubt that Custer’s RIC would have been a First Model, recognizable by forward locking notches on the cylinder.

The caliber would unquestionably have been .442, for even though the British military had adopted the .450 round in 1868, this chambering was not offered in the RIC at the time of the surmised Berkeley Paget gifting.

After the battle Lt. Edward Godfrey, of K Company, 7th Cavalry, noted that during the expedition Custer was carrying “two Bulldog self-cocking, English white handled pistols with a ring in the butt for a lanyard.”

As we have determined, Custer’s RIC was blued with walnut grips and no lanyard ring, so it’s possible that Godfrey might have confused the Webley with the Smith & Wessons which were plated and had pearl grips, though they didn’t have lanyard rings either, and to be fair he did describe Custer’s other gear pretty accurately.

Too, the fact all of the guns seen in the gun rack are currently accounted, for with the exception of the Webley, adds more strong evidence to the assumption the RIC was the gun Custer probably had with him at Greasy Grass.

To date, no .442 cartridge cases have been found on the battlefield, but as things were getting pretty hot and heavy as the Indians approached the troopers at handgun range there’s a good chance that Custer might not have had time to fire off more than a cylinder-full of bullets.

This means that the empty cases could have still been in the gun when it was taken from the commander’s dead body by one of Sitting Bull’s best. Of course, there is also the very real possibility that he never even drew his revolver and used only his .50-70 Remington rifle. There is also the excellent chance he simply had a Colt SAA.

In any event, it is a mystery that will never be completely solved. The chances of the gun turning up with decent provenance after all these years are virtually nil.

Unearthing of spent .442 cases on the battlefield would certainly lend more veracity to Godfrey’s claims but as the round, while uncommon, was not unknown in the West at the time there is no way of conclusively proving they came from a revolver actually fired by Custer.

Read more: http://www.gunsandammo.com/blogs/history-books/what-was-custers-last-gun/#ixzz4xfJRaeCC

Here is some more information about this character:

George Armstrong Custer

| George Armstrong Custer | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | December 5, 1839 New Rumley, Ohio |

| Died | June 25, 1876 (aged 36) Little Bighorn, Montana |

| Buried | Initially on the battlefield; Later reinterred in West Point Cemetery |

| Allegiance | United States of America Union |

| Service/branch | United States Army Union Army |

| Years of service | 1861–1876 |

| Rank | Lieutenant Colonel |

| Commands held | Michigan Brigade 3rd Cavalry Division 2nd Cavalry Division 7th Cavalry Regiment |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

| Awards | see below |

| Spouse(s) | Elizabeth Bacon Custer |

| Relations | Thomas Custer, brother Boston Custer, brother James Calhoun, brother-in-law |

| Signature |  |

George Armstrong Custer (December 5, 1839 – June 25, 1876) was a United States Army officer and cavalry commander in the American Civil War and the American Indian Wars. Raised in Michigan and Ohio, Custer was admitted to West Point in 1857, where he graduated last in his class in 1861. With the outbreak of the Civil War, Custer was called to serve with the Union Army.

Custer developed a strong reputation during the Civil War. He participated in the first major engagement, the First Battle of Bull Runon July 21, 1861, near Washington, D.C. His association with several important officers helped his career as did his success as a highly effective cavalry commander. Custer was brevetted to brigadier general at age 23, less than a week before the Battle of Gettysburg, where he personally led cavalry charges that prevented Confederate cavalry from attacking the Union rear in support of Pickett’s Charge. He was wounded in the Battle of Culpeper Court House in Virginia on September 13, 1863. In 1864, Custer was awarded another star and brevetted to major general rank. At the conclusion of the Appomattox Campaign, in which he and his troops played a decisive role, Custer was present at General Robert E. Lee‘s surrender to General Ulysses S. Grant, on April 9, 1865.

After the Civil War, Custer remained a major general in the United States Volunteers until they were mustered out in February 1866. He reverted to his permanent rank of captain and was appointed a lieutenant colonel in the 7th Cavalry Regiment in July 1866. He was dispatched to the west in 1867 to fight in the American Indian Wars. On June 25, 1876, while leading the 7th Cavalry Regiment at the Battle of the Little Bighorn in Montana Territory against a coalition of Native American tribes, he and all of his detachment—which included two of his brothers—were killed. The battle is popularly known in American history as “Custer’s Last Stand.” Custer and his regiment were defeated so decisively at the Little Bighorn that it has overshadowed all of his prior achievements.

Contents

[hide]

- 1Family and ancestry

- 2Birth, siblings and childhood

- 3Early life

- 4Civil War

- 5Reconstruction duties in Texas

- 6American Indian Wars

- 7Grant, Belknap and politics

- 8Battle of the Little Bighorn

- 9Death

- 10Controversial legacy

- 11Monuments and memorials

- 12Miscellany

- 13Dates of rank

- 14See also

- 15References

- 16Bibliography

- 17External links

- 18Further reading

Family and ancestry[edit]

Custer’s ancestors, Paulus and Gertrude Küster, emigrated to North America around 1693 from the Rhineland in Germany, probably among thousands of Palatine refugees whose passage was arranged by the English government to gain settlers.[1][2]

According to family letters, Custer was named after George Armstrong, a minister, in his devout mother’s hope that her son might join the clergy.[3]

Birth, siblings and childhood[edit]

Custer was born in New Rumley, Ohio, to Emanuel Henry Custer (1806–1892), a farmer and blacksmith, and his second wife, Marie Ward Kirkpatrick (1807–1882).[4] He had two younger brothers, Thomas Custer and Boston Custer, both of whom died with him on the battlefield at Little Bighorn. His other full siblings were the family’s youngest child, Margaret Custer, and Nevin Custer, who suffered from asthma and rheumatism. Custer also had three older half-siblings.[5] It was in this large, close knit family that Custer and his brothers acquired their life-long love of practical jokes.

Emanuel Custer was an outspoken Democrat who taught his children politics and toughness at an early age. In a February 3, 1887 letter to his son’s widow, Libby, he related an incident “when Autie [from his first attempts to pronounce his middle name] was about four years old. He had to have a tooth drawn, and he was very much afraid of blood. When I took him to the doctor to have the tooth pulled, it was in the night and I told him if it bled well it would get well right away, and he must be a good soldier. When he got to the doctor he took his seat, and the pulling began. The forceps slipped off and he had to make a second trial. He pulled it out, and Autie never even scrunched. Going home, I led him by the arm. He jumped and skipped, and said ‘Father you and me can whip all the Whigs in Michigan.’ I thought that was saying a good deal but I did not contradict him.” [6]

Early life[edit]

USMA Cadet George Armstrong “Autie” Custer, ca. 1859

Custer spent much of his boyhood living with his half-sister and brother-in-law in Monroe, Michigan, where he attended school. Before entering the United States Military Academy, Custer attended the McNeely Normal School, later known as Hopedale Normal College, in Hopedale, Ohio. While attending Hopedale, Custer and classmate William Enos Emery were known to have carried coal to help pay for their room and board. After graduating from McNeely Normal School in 1856, Custer taught school in Cadiz, Ohio.[7]

Custer entered West Point as a cadet on July 1, 1857, to become a member of the class of 1862. His class numbered seventy-nine cadets embarking on a five year course of study. With the outbreak of the American Civil War, the course was shortened to four years so that Custer and his class graduated on June 24, 1861. He was 34th in a class of 34 graduates: 23 classmates had dropped out for academic reasons while 22 classmates had resigned to join the Confederacy.[8]

Throughout his life, Custer tested boundaries and rules. In his four years at West Point, he amassed a record-total of 726 demerits, one of the worst conduct records in the history of the academy. A fellow cadet recalled Custer as declaring there were only two places in a class, the head and the foot, and since he had no desire to be the head, he aspired to be the foot. A roommate noted, “It was all right with George Custer, whether he knew his lesson or not: he simply did not allow it to trouble him.”[9] Under ordinary national conditions, Custer’s low class rank would represent a ticket to an obscure posting, but Custer had the fortune to graduate as the Civil War broke out. During his rocky tenure at the Academy, Custer came close to expulsion in each of his three years, due to excessive demerits. Many of these were awarded for pulling pranks on fellow cadets.[citation needed]

Civil War[edit]

McClellan and Pleasonton[edit]

Custer with ex-classmate, friend, and captured Confederate prisoner, Lieutenant James Barroll Washington, an aide to General Johnston, at Fair Oaks, Virginia, 1862

Custer was commissioned a second lieutenant in the 2nd U.S. Cavalry Regiment and was assigned to drilling volunteers in Washington, D.C. On July 21, 1861, he was with his regiment at the First Battle of Bull Run during the Manassas Campaign, where Army commander Winfield Scott detailed him to carry messages to Major General Irvin McDowell. After the battle, he continued participating in the defenses of Washington D.C. until October when he was sick and absent from his unit until February 1862. In March, he participated with the 2nd Cavalry in the Peninsula Campaign (March to August) in Virginia until April 4.

On April 5, he served in the 5th Cavalry Regiment and participated in the Siege of Yorktown, from April 5 to and May 4 and was aide to Major General George B. McClellan; McClellan was in command of the Army of the Potomac during the Peninsula Campaign. On May 24, 1862, during the pursuit of ConfederateGeneral Joseph E. Johnston up the Peninsula, when General Barnard and his staff were reconnoitering a potential crossing point on the Chickahominy River, they stopped, and Custer overheard his commander mutter to himself, “I wish I knew how deep it is.” Custer dashed forward on his horse out to the middle of the river and turned to the astonished officers of the staff and shouted triumphantly, “That’s how deep it is, Mr. General!” Custer then was allowed to lead an attack with four companies of the 4th Michigan Infantry across the Chickahominy River above New Bridge. The attack was successful, resulting in the capture of 50 Confederate soldiers and the seizing of the first Confederate battle flag of the war. McClellan termed it a “very gallant affair” and congratulated Custer personally. In his role as aide-de-camp to McClellan, Custer began his life-long pursuit of publicity.[10] Custer was promoted to the rank of captain on June 5, 1862. On July 17, he was reverted to the rank of first lieutenant. He participated in the Maryland Campaign in September to October, the Battle of South Mountain on September 14, the Battle of Antietam on September 17, and the March to Warrenton, Virginia in October.

Custer (extreme right) with President Lincoln, General McClellanand other officers at the Battle of Antietam, 1862

On June 9, 1863, Custer became aide to Brevet Lieutenant Colonel Alfred Pleasonton, who was now commanding the Cavalry Corps, Army of the Potomac. Recalling his service under Pleasonton, Custer was quoted as saying that “no father could love his son more than General Pleasonton loves me.”[citation needed]Pleasonton’s first assignment was to locate the army of Robert E. Lee, moving north through the Shenandoah Valley in the beginning of what was to become the Gettysburg Campaign.

Brigade command[edit]

Custer (left) with General Pleasonton on horseback in Falmouth, Virginia

Pleasonton was promoted on June 22, 1863 to Major General of U.S. Volunteers. On June 29, after consulting with his new commander, George Meade, Pleasanton began replacing political generals with “commanders who were prepared to fight, to personally lead mounted attacks”.[11] He found just the kind of aggressive fighters he wanted in three of his aides: Wesley Merritt, Elon J. Farnsworth (both of whom had command experience) and George A. Custer. All received immediate promotions; Custer to brigadier general of volunteers, commanding the Michigan Cavalry Brigade (“Wolverines”).[12]

Now a general officer, Custer had great latitude in choosing his uniform. Though often criticized as gaudy, it was more than personal vanity. “A showy uniform for Custer was one of command presence on the battlefield: he wanted to be readily distinguishable at first glance from all other soldiers. He intended to lead from the front, and to him it was a crucial issue of unit morale that his men be able to look up in the middle of a charge, or at any other time on the battlefield, and instantly see him leading the way into danger.” [13]

Some have claimed Custer’s leadership in battle as reckless or foolhardy. However, he “meticulously scouted every battlefield, gauged the enemies [sic] weak points and strengths, ascertained the best line of attack and only after he was satisfied was the ‘Custer Dash’ with a Michigan yell focused with complete surprise on the enemy in routing them every time.”[14]

Hanover and Abbottstown[edit]

On June 30, 1863, Custer and the First and Seventh Michigan Cavalry had just passed through Hanover, Pennsylvania, while the Fifth and Sixth Michigan Cavalry followed about seven miles behind. Hearing gunfire, he turned and started to the sound of the guns. A courier reported that Farnsworth’s Brigade had been attacked by rebel cavalry from side streets in the town. Reassembling his command, he received orders from Kilpatrick to engage the enemy northeast of town near the railway station. Custer deployed his troops and began to advance. After a brief firefight, the rebels withdrew to the northeast. This seemed odd, since it was supposed that Lee and his army were somewhere to the west. Though seemingly of little consequence, this skirmish further delayed Stuart from joining Lee. Further, as Captain James H. Kidd, commander of F troop, Sixth Michigan Cavalry, later wrote: “Under [Custer’s] skillful hand the four regiments were soon welded into a cohesive unit….” [15]

Next morning, July 1, 1863, they passed through Abbottstown, Pennsylvania, still searching for Stuart’s cavalry. Late in the morning they heard sounds of gunfire from the direction of Gettysburg. At Heidlersburg, Pennsylvania, that night they learned that General John Buford‘s cavalry had found Lee’s army at Gettysburg. The next morning, July 2, 1863, orders came to hurry north to disrupt General Richard S. Ewell‘s communications and relieve the pressure on the union forces. By mid afternoon, as they approached Hunterstown, Pennsylvania, they encountered Stuart’s cavalry.[16] Custer rode alone ahead to investigate and found that the rebels were unaware of the arrival of his troops. Returning to his men, he carefully positioned them along both sides of the road where they would be hidden from the rebels. Further along the road, behind a low rise, he positioned the First and Fifth Michigan Cavalry and his artillery, under the command of Lieutenant Alexander Cummings McWhorter Pennington, Jr. To bait his trap, he gathered A Troop, Sixth Michigan Cavalry, called out, “Come on boys, I’ll lead you this time!” and galloped directly at the unsuspecting rebels. As he had expected, the rebels, “more than two hundred horsemen, came racing down the country road” after Custer and his men. He lost half of his men in the deadly rebel fire and his horse went down, leaving him on foot.[17] He was rescued by Private Norvell Francis Churchill of the 1st Michigan Cavalry, who galloped up, shot Custer’s nearest assailant, and pulled Custer up behind him.[18] Custer and his remaining men reached safety, while the pursuing rebels were cut down by slashing rifle fire, then canister from six canons. The rebels broke off their attack, and both sides withdrew.

After spending most of the night in the saddle, Custer’s brigade arrived at Two Taverns, Pennsylvania roughly five miles southeast of Gettysburg around 3 A. M. July 3, 1863. There he was joined by Farnsworth’s brigade. By daybreak they received orders to protect Meade’s flanks. He was about to experience perhaps his finest hours during the war.

Gettysburg[edit]

Lee’s battle plan, shared with less than a handful of subordinates, was to defeat Meade through a combined assault by all of his resources. Longstreet would attack Cemetery Hill from the west, Stuart would attack Culp’s Hill from the southeast and Ewell would attack Culps’ Hill from the north. Once the Union forces holding Culp’s Hill had collapsed, the rebels would “roll up” the remaining Union defenses on Cemetery Ridge. To accomplish this, he sent Stuart with six thousand cavalrymen and mounted infantry on a long, flanking maneuver.[19]

By mid-morning, Custer had arrived at the intersection of Old Dutch road and Hanover Road. He was later joined by Brigadier General David McMurtrie Gregg, who had him deploy his men at the northeast corner. Custer then sent out scouts to investigate nearby wooded areas. Gregg, meanwhile, placed Colonel John Baillie McIntosh‘s brigade near the intersection and sent the rest of his command to picket duty along two miles to the southwest. After making additional deployments, that left 2,400 cavalry under McIntosh and 1,200 under Custer, together with Colonel Alexander Cummings McWhorter Pennington, Jr.‘s and Captain Alanson Merwin Randol‘s artillery, a total of ten three-inch guns.

About noon Custer’s men heard cannon fire, Stuart’s signal to Lee that he was in position and had not been detected. About the same time Gregg received a message warning that a large body of rebel cavalry had moved out the York Pike and might be trying to get around the Union right. A second message, from Pleasonton, ordered Gregg to send Custer to cover the Union far left. Since Gregg had already sent most of his force off to other duties, it was clear to both Gregg and Custer that Custer must remain. They had about 2700 men facing 6000 Confederates.

Soon afterward fighting broke out between the skirmish lines. Stuart ordered an attack by his mounted infantry under General Albert G. Jenkins, but the Union line- men from the First Michigan cavalry, the First New Jersey Cavalry and the Third Pennsylvania Cavalry– held. Stuart ordered Jackson’s four gun battery into action. Custer ordered Pennington to answer. After a brief exchange in which two of Jackson’s guns were destroyed, there was a lull.

About one o’clock, the massive Confederate artillery barrage in support of the upcoming assault on Cemetery Ridge began. Jenkins’ men renewed the attack, but soon ran out of ammunition and fell back. Resupplied, they again pressed the attack. Outnumbered, the Union cavalry fell back, firing as they went. Custer sent most of his Fifth Michigan cavalry ahead on foot, forcing Jenkins’ men to fall back. Jenkins’ men were reinforced by about 150 sharpshooters from General Fitzhugh Lee‘s brigade and, shortly after, Stuart ordered a mounted charge by the Ninth Virginia Cavalry and the Thirteenth Virginia Cavalry. Now it was Custer’s men who were running out of ammunition. The Fifth Michigan was forced back and the battle was reduced to vicious, hand-to-hand combat.

Seeing this, Custer mounted a counter- attack, riding ahead of the fewer than 400 new troopers of the Seventh Michigan Cavalry, shouting, “Come on, you Wolverines!” As he swept forward, he formed a line of squadrons five ranks deep- five rows of eighty horsemen side by side- chasing the retreating rebels until their charge was stopped by a wood rail fence. The horses and men became jammed into a solid mass and were soon attacked on their left flank by the dismounted Ninth and Thirteenth Virginia Cavalry and on the right flank by the mounted First Virginia cavalry. Custer extricated his men and raced south to the protection of Pennington’s artillery near Hanover Road. The pursuing Confederates were cut down by canister, then driven back by the remounted Fifth Michigan Cavalry. Both forces withdrew to a safe distance to regroup.

It was then about three o’clock. The artillery barrage to the west had suddenly stopped. Union soldiers were surprised to see Stuart’s entire force about a half mile away, coming toward them, not in line of battle, but “formed in close column of squadrons… A grander spectacle than their advance has rarely been beheld”.[20] Stuart recognized he now had little time to reach and attack the Union rear along Cemetery Ridge. He must make one, last effort to break through the Union cavalry.

Stuart passed by McIntosh’s cavalry- the First New Jersey, Third Pennsylvania and Company A of Purnell’s Legion- posted about half way down the field, with relative ease. As he approached, they were ordered back into the woods, without slowing down Stuart’s column, “advancing as if in review, with sabers drawn and glistening like silver in the bright sunlight….” [21]

Stuart’s last obstacle was Custer, with four hundred veteran troopers of the First Michigan Cavalry, directly in his path. Outnumbered but undaunted, Custer rode to the head of the regiment, “drew his saber, threw off his hat so they could see his long yellow hair” and shouted… “Come on, you Wolverines!”[22] Custer formed his men in line of battle and charged. “So sudden was the collision that many of the horses were turned end over end and crushed their riders beneath them….”[23] As the Confederate advance stopped, their right flank was struck by troopers of the Fifth, Sixth and Seventh Michigan. McIntosh was able to gather some of his men from the First New Jersey and Third Pennsylvania and charged the rebel left flank. “Seeing that the situation was becoming critical, I [Captain Miller] turned to [Lieutenant Brooke-Rawle] and said: “I have been ordered to hold this position, but, if you will back me up in case I am court-martialed for disobedience, I will order a charge.”[24] The rebel column disintegrated into individual saber and pistol fights.

Within twenty minutes the combatants heard the sound of the Union artillery opening up on Pickett’s men. Stuart knew that whatever chance he had of joining the Confederate assault was gone. He withdrew his men to Cress Ridge.[25]

Custer’s brigade lost 257 men at Gettysburg, the highest loss of any Union cavalry brigade.[26] “I challenge the annals of warfare to produce a more brilliant or successful charge of cavalry”, Custer wrote in his report.[27] “For Gallant And Meritorious Services”, he was awarded a regular army brevet promotion to Major.

Marriage[edit]

On February 9, 1864, Custer married Elizabeth Clift Bacon (1842–1933), whom he had first seen when he was ten years old.[28] He had been socially introduced to her in November 1862, when home in Monroe on leave. She was not initially impressed with him,[29] and her father, Judge Daniel Bacon, disapproved of Custer as a match because he was the son of a blacksmith. It was not until well after Custer had been promoted to the rank of brevet brigadier general that he gained the approval of Judge Bacon. He married Elizabeth Bacon fourteen months after they formally met.[30]

In November 1868, following the Battle of Washita River, Custer was alleged (by Captain Frederick Benteen, chief of scouts Ben Clark, and Cheyenne oral tradition) to have unofficially married Mo-nah-se-tah, daughter of the Cheyenne chief Little Rock in the winter or early spring of 1868–1869 (Little Rock was killed in the one-day action at Washita on November 27).[31] Mo-nah-se-tah gave birth to a child in January 1869, two months after the Washita battle. Cheyenne oral history tells that she also bore a second child, fathered by Custer in late 1869. Some historians, however, believe that Custer had become sterile after contracting gonorrhea while at West Point and that the father was, in actuality, his brother Thomas.[32] A descendant of the second child, who goes by the name Gail Custer, wrote a book about the affair.[33] Clarke’s description in his memoirs included the statement, “Custer picked out a fine looking one and had her in his tent every night.”[34]

The Valley and Appomattox[edit]

In 1864, with the Cavalry Corps of the Army of the Potomac reorganized under the command of Major General Philip Sheridan, Custer (now commanding the 3rd Division) led his “Wolverines” to the Shenandoah Valley where by the year’s end they defeated the army of Confederate Lieutenant General Jubal Early in the Valley Campaigns of 1864. During May and June, Sheridan and Custer (Captain, 5th Cavalry, May 8 and Brevet Lieutenant Colonel, May 11) took part in cavalry actions supporting the Overland Campaign, including the Battle of the Wilderness (after which Custer ascended to divisioncommand), and the Battle of Yellow Tavern (where J.E.B. Stuart was mortally wounded). In the largest all-cavalry engagement of the war, the Battle of Trevilian Station, in which Sheridan sought to destroy the Virginia Central Railroadand the Confederates’ western resupply route, Custer captured Hampton’s divisional train, but was then cut off and suffered heavy losses (including having his division’s trains overrun and his personal baggage captured by the enemy) before being relieved. When Lieutenant General Early was then ordered to move down the Shenandoah Valley and threaten Washington, D.C., Custer’s division was again dispatched under Sheridan. In the Valley Campaigns of 1864, they pursued the Confederates at the Third Battle of Winchester and effectively destroyed Early’s army during Sheridan’s counterattack at Cedar Creek.

Sheridan and Custer, having defeated Early, returned to the main Union Army lines at the Siege of Petersburg, where they spent the winter. In April 1865 the Confederate lines finally broke, and Robert E. Lee began his retreat to Appomattox Court House, pursued by the Union cavalry. Custer distinguished himself by his actions at Waynesboro, Dinwiddie Court House, and Five Forks. His division blocked Lee’s retreat on its final day and received the first flag of truce from the Confederate force. Custer was present at the surrender at Appomattox Court House and the table upon which the surrender was signed was presented to him as a gift for his wife by General Philip Sheridan, who included a note to her praising Custer’s gallantry. She treasured the gift of the historical table, which is now in the Smithsonian Institution.[35]

On April 25, after the war officially ended, Custer had his men search for, then illegally seize a large, prize racehorse “Don Juan” near Clarksville, Virginia, worth then an estimated $10,000 (several hundred thousand today), along with his written pedigree. Custer rode Don Juan in the grand review victory parade in Washington, D.C. on May 23, creating a sensation when the scared thoroughbred bolted. The owner, Richard Gaines, wrote to General Grant, who then ordered Custer to return the horse to Gaines, but he did not, instead hiding the horse and winning a race with it the next year, before the horse died suddenly.[36]

Promotions and ranks[edit]

Custer’s promotions and ranks including his six brevet [temporary] promotions which were all for gallant and meritorious services at five different battles and one campaign:[37]

Second Lieutenant, 2nd Cavalry: June 24, 1861

First Lieutenant, 5th Cavalry: July 17, 1862

Captain Staff, Additional Aide-De-Camp: June 5, 1862

Brigadier General, U.S. Volunteers: June 29, 1863

Brevet Major, July 3, 1863 (Battle of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania)

Captain, 5th Cavalry: May 8, 1864

Brevet Lieutenant Colonel: May 11, 1864 (Battle of Yellow Tavern – Combat at Meadow)

Brevet Colonel: September 19, 1864(Battle of Winchester, Virginia)

Brevet Major General, U.S. Volunteers: October 19, 1864 (Battle of Winchester and Fisher’s Hill, Virginia)

Brevet Brigadier General, U.S. Army, March 13, 1865 (Battle of Five Forks, Virginia)

Brevet Major General, U.S. Army: March 13, 1865 (The campaign ending in the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia)

Major General, U.S. Volunteers: April 15, 1865

Mustered out of Volunteer Service: February 1, 1866

Lieutenant Colonel, 7th Cavalry: July 28, 1866 (killed at the Battle of the Little Bighorn, June 25, 1876)

Reconstruction duties in Texas[edit]

On June 3, 1865, at Sheridan’s behest, Major General Custer accepted command of the 2nd Division of Cavalry, Military Division of the Southwest, to march from Alexandria, Louisiana, to Hempstead, Texas, as part of the Union occupation forces. Custer arrived at Alexandria on June 27 and began assembling his units, which took more than a month to gather and remount. On July 17, he assumed command of the Cavalry Division of the Military Division of the Gulf (on August 5, officially named the 2nd Division of Cavalry of the Military Division of the Gulf), and accompanied by his wife, he led the division (five regiments of veteran Western Theater cavalrymen) to Texas on an arduous 18-day march in August. On October 27, the division departed to Austin. On October 29, Custer moved the division from Hempstead to Austin, arriving on November 4. Major General Custer became Chief of Cavalry of the Department of Texas, from November 13 to February 1, 1866, succeeding Major General Wesley Merritt.

During his entire period of command of the division, Custer encountered considerable friction and near mutiny from the volunteer cavalry regiments who had campaigned along the Gulf coast. They desired to be mustered out of Federal service rather than continue campaigning, resented imposition of discipline (particularly from an Eastern Theater general), and considered Custer nothing more than a vain dandy.[38][39]

Custer’s division was mustered out beginning in November 1865, replaced by the regulars of the U.S. 6th Cavalry Regiment. Although their occupation of Austin had apparently been pleasant, many veterans harbored deep resentments against Custer, particularly in the 2nd Wisconsin Cavalry, because of his attempts to maintain discipline. Upon its mustering out, several members planned to ambush Custer, but he was warned the night before and the attempt thwarted.[40]

American Indian Wars[edit]

Custer (left) posing with Grand Duke Alexei Alexandrovich of Russia, 1872

Custer and his wife at Fort Abraham Lincoln, Dakota Territory, 1874

On February 1, 1866, Major General Custer mustered out of the U.S. volunteer service and took an extended leave of absence and awaited orders to September 24.[41] He explored options in New York City,[42] where he considered careers in railroads and mining.[43] Offered a position (and $10,000 in gold) as adjutant general of the army of Benito Juárez of Mexico, who was then in a struggle with the Mexican Emperor Maximilian I (a satellite ruler of French Emperor Napoleon III), Custer applied for a one-year leave of absence from the U.S. Army, which was endorsed by Grant and Secretary of War Stanton. Sheridan and Mrs. Custer disapproved, however, and when his request for leave was opposed by U.S. Secretary of State William H. Seward, who was against having an American officer commanding foreign troops, Custer refused the alternative of resignation from the Army to take the lucrative post.[43][44]

Following the death of his father-in-law in May 1866, Custer returned to Monroe, Michigan, where he considered running for Congress. He took part in public discussion over the treatment of the American South in the aftermath of the Civil War, advocating a policy of moderation.[43] He was named head of the Soldiers and Sailors Union, regarded as a response to the hyper-partisan Grand Army of the Republic (GAR). Also formed in 1866, it was led by Republican activist John Alexander Logan. In September 1866 Custer accompanied President Andrew Johnson on a journey by train known as the “Swing Around the Circle” to build up public support for Johnson’s policies towards the South. Custer denied a charge by the newspapers that Johnson had promised him a colonel’s commission in return for his support, but Custer had written to Johnson some weeks before seeking such a commission. Custer and his wife stayed with the president during most of the trip. At one point Custer confronted a small group of Ohio men who repeatedly jeered Johnson, saying to them: “I was born two miles and a half from here, but I am ashamed of you.”[45]

On July 28, 1866, Custer was appointed lieutenant colonel of the newly created 7th Cavalry Regiment,[46] which was headquartered at Fort Riley, Kansas.[47] He served on frontier duty at Fort Riley from October 18 to March 26, and scouted in Kansas and Colorado to July 28. 1867. He took part in Major General Winfield Scott Hancock‘s expedition against the Cheyenne. On June 26, Lt. Lyman Kidder’s party, made up of ten troopers and one scout, were massacred while en route to Fort Wallace. Lt. Kidder was to deliver dispatches to Custer from General Sherman, but his party was attacked by Lakota Sioux and Cheyenne (see Kidder massacre). Days later, Custer and a search party found the bodies of Kidder’s patrol.

Following the Hancock campaign, Custer was arrested and suspended at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas to August 12, 1868 for being AWOL, after having abandoned his post to see his wife. At the request of Major General Sheridan, who wanted Custer for his planned winter campaign against the Cheyenne, Custer was allowed to return to duty before his one-year term of suspension had expired and joined his regiment to October 7, 1868. He then went on frontier duty, scouting in Kansas and Indian Territoryto October 1869.

Under Sheridan’s orders, Custer took part in establishing Camp Supply in Indian Territory in early November 1868 as a supply base for the winter campaign. On November 27, 1868, Custer led the 7th Cavalry Regiment in an attack on the Cheyenne encampment of Chief Black Kettle — the Battle of Washita River. Custer reported killing 103 warriors and some women and children; 53 women and children were taken as prisoners. Estimates by the Cheyenne of their casualties were substantially lower (11 warriors plus 19 women and children).[48] Custer had his men shoot most of the 875 Indian ponies they had captured.[49] The Battle of Washita River was regarded as the first substantial U.S. victory in the Southern Plains War, and it helped force a significant portion of the Southern Cheyenne onto a U.S.-assigned reservation.

In 1873, Custer was sent to the Dakota Territory to protect a railroad survey party against the Lakota. On August 4, 1873, near the Tongue River, Custer and the 7th Cavalry Regiment clashed for the first time with the Lakota. One man on each side was killed. In 1874 Custer led an expedition into the Black Hills and announced the discovery of gold on French Creek near present-day Custer, South Dakota. Custer’s announcement triggered the Black Hills Gold Rush. Among the towns that immediately grew up was Deadwood, South Dakota, notorious for lawlessness.

Grant, Belknap and politics[edit]

| This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2013) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

In 1875, the Grant administration attempted to buy the Black Hills region from the Sioux. When the Sioux refused to sell, they were ordered to report to reservations by the end of January, 1876. Mid-winter conditions made it impossible for them to comply. The administration labeled them “hostiles” and tasked the Army with bringing them in. Custer was to command an expedition planned for the spring, part of a three-pronged campaign. While Custer’s expedition marched west from Fort Abraham Lincoln, near present-day Mandan, North Dakota, troops under Colonel John Gibbon were to march east from Fort Ellis, near present-day Bozeman, Montana while a force under General George Crook was to march north from Fort Fetterman, near present-day Douglas, Wyoming.

Custer’s 7th Cavalry was originally scheduled to leave Fort Abraham Lincoln on April 6, 1876, but on March 15 he was summoned to Washington to testify at congressional hearings. Rep. Hiester Clymer‘s Committee was investigating alleged corruption involving Secretary of War William W. Belknap (who had resigned March 2), President Grant’s brother Orvil and traders granted monopolies at frontier Army posts.[50] It was alleged that Belknap had been selling these lucrative trading post positions where soldiers were required to make their purchases. Custer himself had experienced first hand the high prices being charged at Fort Lincoln.[51]

Concerned that he might miss the coming campaign, Custer did not want to go to Washington. He asked to answer questions in writing, but Clymer insisted.[52] Recognizing that his testimony would be explosive, Custer tried “to follow a moderate and prudent course, avoiding prominence.” [53] Despite his care, his testimony was a sensation: Custer was sharply criticized by the Republican press and loudly praised by the Democratic press.

After Custer testified on March 29 and April 4, Belknap was impeached and the case sent to the Senate for trial. Custer asked the impeachment managers to release him from further testimony. With the help of a request from his superior, Brigadier General Alfred Terry, Commander of the Department of Dakota, he was excused. Then President Ulysses S. Grant intervened.

The Congressional investigation had created a serious rift with Grant. Custer had written articles published anonomously in The New York Herald that exposed trader post kickback rings and implied that Belknap was behind the rings. Moreover, during the investigation, Custer testified on hearsay evidence that President Grant’s brother Orvil was involved. Grant had also not forgotten that Custer had once arrested his son Fred for drunkenness. Infuriated, Grant decided to retaliate by stripping Custer of his command in the upcoming campaign.

General Terry protested, saying he had no available officers of rank qualified to replace Custer. Both Sheridan and Sherman wanted Custer in command but had to support Grant. General Sherman, hoping to resolve the issue, advised Custer to meet personally with President Grant before leaving Washington. Three times Custer requested meetings with Grant, but each request was refused.[54]

Finally, Custer gave up and took a train to Chicago on May 2, planning to rejoin his regiment. A furious Grant ordered Sheridan to arrest Custer for leaving Washington without permission. On May 3, a member of Sheridan’s staff arrested Custer as he arrived in Chicago.[55] The arrest sparked public outrage. The New York Herald called Grant the “modern Caesar” and asked, “Are officers… to be dragged from railroad trains and ignominiously ordered to stand aside until the whims of the Chief magistrate … are satisfied?”[56]

Grant relented but insisted that Terry- not Custer- personally command the expedition. Terry met Custer in St. Paul, Minnesota on May 6. He later recalled, “(Custer) with tears in his eyes, begged for my aid. How could I resist it?”[57] Terry wrote to Grant attesting to the advantages of Custer’s leading the expedition. Sheridan endorsed his effort, accepting Custer’s “guilt” and suggesting his restraint in future.

Grant was already under pressure for his treatment of Custer. His administration worried that if the “Sioux campaign” failed without Custer, then Grant would be blamed for ignoring the recommendations of senior Army officers. On May 8, Custer was told that he would lead the expedition, but only under Terry’s direct supervision.

Elated, Custer told General Terry’s chief engineer, Captain Ludlow, that he would “cut loose” from Terry and operate independently.[58]

Battle of the Little Bighorn[edit]

By the time of Custer’s Black Hills expedition in 1874, the level of conflict and tension between the U.S. and many of the Plains Indians tribes (including the Lakota Sioux and the Cheyenne) had become exceedingly high. European-Americans continually broke treaty agreements and advanced further westward, resulting in violence and acts of depredation by both sides. To take possession of the Black Hills (and thus the gold deposits), and to stop Indian attacks, the U.S. decided to corral all remaining free Plains Indians. The Grant government set a deadline of January 31, 1876 for all Lakota and Arapaho wintering in the “unceded territory” to report to their designated agencies (reservations) or be considered “hostile”.[59]

The 7th Cavalry, Custer commanding, departed from Fort Abraham Lincoln on May 17, 1876, part of a larger army force planning to round up remaining free Indians. Meanwhile, in the spring and summer of 1876, the Hunkpapa Lakota holy man Sitting Bull had called together the largest ever gathering of Plains Indians at Ash Creek, Montana (later moved to the Little Bighorn River) to discuss what to do about the whites.[60] It was this united encampment of Lakota, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapaho Indians that the 7th met at the Battle of the Little Bighorn in the Crow Indian Reservation[61]created in old Crow Country. (In the Fort Laramie Treaty (1851), the valley of the Little Bighorn is in the heart of the Crow Indian treaty territory and accepted as such by the Lakota, the Cheyenne and the Arapaho).[62] The Lakotas were staying in the valley without consent from the Crow tribe,[63] which sided with the Army to expel the Indian invaders.[64]

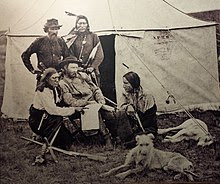

Custer and Bloody Knife (kneeling left), Custer’s favorite Indian Scout

About June 15, Reno, while on a scout, discovered the trail of a large village on the Rosebud River.[65] On June 22, Custer’s entire regiment was detached to follow this trail. On June 25, some of Custer’s Crow Indian scouts identified what they claimed was a large Indian encampment in the valley near the Little Bighorn River. Custer had first intended to attack the Indian village the next day, but since his presence was known, he decided to attack immediately and divided his forces into three battalions: one led by Major Marcus Reno, one by Captain Frederick Benteen, and one by himself. Captain Thomas M. McDougall and Company B were with the pack train. Reno was sent north to charge the southern end of the encampment, Custer rode north, hidden to the east of the encampment by bluffs and planning to circle around and attack from the north,[66][67] and Benteen was sent south and west to cut off any attempted escape by the Indians.

Reno began a charge on the southern end of the village but halted some 500–600 yards short of the camp, and had his men dismount and form a skirmish line.[68] They were soon overcome by mounted Lakota and Cheyenne warriors who counterattacked en masse against Reno’s exposed left flank,[69] forcing Reno and his men to take cover in the trees along the river. Eventually, however, this position became untenable, and the troopers were forced into a bloody retreat up onto the bluffs above the river, where they made their own stand.[70][71] This, the opening action of the battle, cost Reno a quarter of his command.

Custer may have seen Reno stop and form a skirmish line as Custer led his command to the northern end of the main encampment, where he apparently planned to sandwich the Indians between his attacking troopers and Reno’s command in a “hammer and anvil” maneuver.[72] According to Grinnell’s account, based on the testimony of the Cheyenne warriors who survived the fight,[73] at least part of Custer’s command attempted to ford the river at the north end of the camp but were driven off by stiff resistance from Indian sharpshooters firing from the brush along the west bank of the river. From that point the soldiers were pursued by hundreds of warriors onto a ridge north of the encampment. Custer and his command were prevented from digging in by Crazy Horse, however, whose warriors had outflanked him and were now to his north, at the crest of the ridge.[74] Traditional white accounts attribute to Gall the attack that drove Custer up onto the ridge, but Indian witnesses have disputed that account.[75]

—Famous words reportedly said by General Custer shortly before being killed.[76]

For a time, Custer’s men appear to have been deployed by company, in standard cavalry fighting formation—the skirmish line, with every fourth man holding the horses, though this arrangement would have robbed Custer of a quarter of his firepower. Worse, as the fight intensified, many soldiers could have taken to holding their own horses or hobbling them, further reducing the 7th’s effective fire. When Crazy Horse and White Bull mounted the charge that broke through the center of Custer’s lines, pandemonium may have broken out among the soldiers of Calhoun’s command,[77] though Myles Keogh‘s men seem to have fought and died where they stood. According to some Lakota accounts, many of the panicking soldiers threw down their weapons[78] and either rode or ran towards the knoll where Custer, the other officers, and about 40 men were making a stand. Along the way, the warriors rode them down, counting coup by striking the fleeing troopers with their quirts or lances.[79]

Initially, Custer had 208 officers and men under his command, with an additional 142 under Reno, just over 100 under Benteen, 50 soldiers with Captain McDougall’s rearguard, and 84 soldiers under 1st Lieutenant Edward Gustave Mathey with the pack train. The Lakota-Cheyenne coalition may have fielded over 1800 warriors.[80] Historian Gregory Michno settles on a low number around 1000, based on contemporary Lakota testimony, but other sources place the number at 1800 or 2000, especially in the works by Utley and Fox. The 1800–2000 figure is substantially lower than the higher numbers of 3000 or more postulated by Ambrose, Gray, Scott, and others. Some of the other participants in the battle gave these estimates:

-

- Spotted Horn Bull – 5,000 braves and leaders

- Maj. Reno – 2,500 to 5,000 warriors

- Capt. Moylan – 3,500 to 4,000

- Lt. Hare – not under 4,000

- Lt. Godfrey – minimum between 2,500 and 3,000

- Lt. Edgerly – 4,000

- Lt. Varnum – not less than 4,000

- Sgt. Kanipe – fully 4,000

- George Herendeen – fully 3,000

- Fred Gerard – 2,500 to 3,000

An average of the above is 3,500 Indian warriors and leaders.[81]

As the troopers were cut down, the native warriors stripped the dead of their firearms and ammunition, with the result that the return fire from the cavalry steadily decreased, while the fire from the Indians constantly increased. The surviving troopers apparently shot their remaining horses to use as breastworks for a final stand on the knoll at the north end of the ridge. The warriors closed in for the final attack and killed every man in Custer’s command. As a result, the Battle of the Little Bighorn has come to be popularly known as “Custer’s Last Stand”.

Death[edit]

It is unlikely any Native American recognized Custer during or after the battle. Michno summarizes: “Shave Elk said ‘We did not suspect that we were fighting Custer and did not recognize him either alive or dead.’ Wooden Leg said no one could recognize any enemy during the fight, for they were too far away. The Cheyennes did not even know a man named Custer was in the fight until weeks later. Antelope said none knew of Custer being at the fight until they later learned of it at the agencies. Thomas Marquis learned from his interviews that no Indian knew Custer was at the Little Bighorn fight until months later. Many Cheyennes were not even aware that other members of the Custer family had been in the fight until 1922, when, Marquis said, he himself first informed them of that fact.”[82]

Nevertheless, several individuals claimed personal responsibility for the killing, including White Bull of the Miniconjous, Rain-in-the-

A contrasting version of Custer’s death is suggested by the testimony of an Oglala named Joseph White Cow Bull, according to novelist and Custer biographer Evan Connell, who relates that Joseph White Bull stated he had shot a rider wearing a buckskin jacket and big hat at the riverside when the soldiers first approached the village from the east. The initial force facing the soldiers, according to this version, was quite small (possibly as few as four warriors) yet challenged Custer’s command. The rider who was hit was mounted next to a rider who bore a flag and had shouted orders that prompted the soldiers to attack, but when the buckskin-clad rider fell off his horse after being shot, many of the attackers reined up. The allegation that the buckskin-clad officer was Custer, if accurate, might explain the supposed rapid disintegration of Custer’s forces.[85] However, several other officers of the Seventh, including William Cooke and Tom Custer, were also dressed in buckskin on the day of the battle, and the fact that each of the non-mutilation wounds to George Custer’s body (a bullet wound below the heart and a shot to the left temple) would have been instantly fatal casts doubt on his being wounded or killed at the ford, more than a mile from where his body was found.[86] The circumstances are, however, consistent with David Humphreys Miller‘s suggestion that Custer’s attendants would not have left his dead body behind to be desecrated.[87]

During the 1920s, two elderly Cheyenne women spoke briefly with oral historians about their having recognized Custer’s body on the battlefield and had stopped a Sioux warrior from desecrating the body. The women were relatives of Mo-nah-se-tah‘s, who was alleged to have been Custer’s one-time lover. In the Cheyenne culture of the time, such a relationship was considered a marriage. The women allegedly told the warrior: “Stop, he is a relative of ours,” and then shooed him away. The two women then shoved their sewing awls into his ears to permit Custer’s corpse to “hear better in the afterlife” because he had broken his promise to Stone Forehead never to fight against Native Americans again.[88]

When the main column under General Terry arrived two days later, the army found most of the soldiers’ corpses stripped, scalped, and mutilated.[89][90] Custer’s body had two bullet holes, one in the left temple and one just below the heart.[91]Capt. Benteen, who inspected the body, stated that in his opinion the fatal injuries had not been the result of .45 caliber ammunition, which implies the bullet holes had been caused by ranged rifle fire.[92] Some time later, Lieutenant Edward S. Godfrey described Custer’s mutilation, telling Charles F. Bates that “an arrow had been forced up his penis.”[93]

The bodies of Custer and his brother Tom were wrapped in canvas and blankets, then buried in a shallow grave, covered by the basket from a travois held in place by rocks. When soldiers returned a year later, the brothers’ grave had been broken into by animals and the bones scattered. “Not more than a double handful of small bones were picked up.”[94]Custer was reinterred with full military honors at West Point Cemetery on October 10, 1877. The battle site was designated a National Cemetery in 1876.

Controversial legacy[edit]

Public relations and media coverage during his lifetime[edit]

Custer has been called a “media personality“,[95][96] and he valued good public relations and used the print media of his era effectively. He frequently invited journalists to accompany his campaigns (one, Associated Press reporter Mark Kellogg, died at the Little Bighorn), and their favorable reporting contributed to his high reputation, which lasted well into the latter 20th century.

Custer enjoyed writing, often writing all night long. He wrote a series of magazine articles of his experiences on the frontier, which were published book form as My Life on the Plains in 1874. The work is still a valued primary source for information on US-Native relations.

Posthumous legacy[edit]

After his death, Custer achieved lasting fame. The public saw him as a tragic military hero and exemplary gentleman who sacrificed his life for his country.

Custer’s wife, Elizabeth, who had accompanied him in many of his frontier expeditions, did much to advance this view with the publication of several books about her late husband: Boots and Saddles, Life with General Custer in Dakota,[97] Tenting on the Plains, or General Custer in Kansas and Texas[98] and Following the Guidon.[99] The deaths of Custer and his troops became the best-known episode in the history of the American Indian Wars, due in part to a painting commissioned by the brewery Anheuser-Busch as part of an advertisingcampaign. The enterprising company ordered reprints of a dramatic work that depicted “Custer’s Last Stand” and had them framed and hung in many United States saloons. This created lasting impressions of the battle and the brewery’s products in the minds of many bar patrons.[100] Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wrote an adoring (and in some places, erroneous) poem.[101] President Theodore Roosevelt‘s lavish praise pleased Custer’s widow.[102]

President Grant, a highly successful general but recent antagonist, criticized Custer’s actions in the battle of the Little Bighorn. Quoted in the New York Herald on September 2, 1876, Grant said, “I regard Custer’s Massacre as a sacrifice of troops, brought on by Custer himself, that was wholly unnecessary – wholly unnecessary.”[103] General Phillip Sheridan likewise took a harsh view of Custer’s final military actions.[citation needed]

General Nelson Miles (who inherited Custer’s mantle of famed Indian fighter) and others praised him as a fallen hero betrayed by the incompetence of subordinate officers. Miles noted the difficulty of winning a fight “with seven-twelfths of the command remaining out of the engagement when within sound of his rifle shots.”[104]

The assessment of Custer’s actions during the American Indian Wars has undergone substantial reconsideration in modern times. Documenting the arc of popular perception in his biography Son of the Morning Star (1984), author Evan Connell notes the reverential tone of Custer’s first biographer Frederick Whittaker (whose book was rushed out the year of Custer’s death.)[105] Connell concludes:

These days it is stylish to denigrate the general, whose stock sells for nothing. Nineteenth-century Americans thought differently. At that time he was a cavalier without fear and beyond reproach.[106]

Criticism and controversy[edit]

—from Touched by Fire: The Life, Death, and Mythic Afterlife of George Armstrong Custer by Louise Barnett.[103]

The controversy over blame for the disaster at Little Bighorn continues to this day. Major Marcus Reno‘s failure to press his attack on the south end of the Lakota/Cheyenne village and his flight to the timber along the river, after a single casualty, have been cited as a factor in the destruction of Custer’s battalion, as has Captain Frederick Benteen‘s allegedly tardy arrival on the field, and the failure of the two officers’ combined forces to move toward the relief of Custer.[107]Some of Custer’s critics have asserted tactical errors.[citation needed]

- While camped at Powder River, Custer refused the support offered by General Terry on June 21, of an additional four companies of the Second Cavalry. Custer stated that he “could whip any Indian village on the Plains” with his own regiment, and that extra troops would simply be a burden.

- At the same time, he left behind at the steamer Far West, on the Yellowstone, a battery of Gatling guns, knowing he was facing superior numbers. Before leaving the camp all the troops, including the officers, also boxed their sabers and sent them back with the wagons.[108]

- On the day of the battle, Custer divided his 600-man command, despite being faced with vastly superior numbers of Sioux and Cheyenne.

- The refusal of an extra battalion reduced the size of his force by at least a sixth, and rejecting the firepower offered by the Gatling guns played into the events of June 25 to the disadvantage of his regiment.[109]

Custer’s defenders, however, including historian Charles K. Hofling, have asserted that Gatling guns would have been slow and cumbersome as the troops crossed the rough country between the Yellowstone and the Little Bighorn.[110] Custer rated speed in gaining the battlefield as essential and more important. Other Custer supporters[who?] have claimed that splitting the forces was a standard tactic, so as to demoralize the enemy with the appearance of the cavalry in different places all at once, especially when a contingent threatened the line of retreat.

Monuments and memorials[edit]

Custer Memorial at his birthplace in New Rumley, Ohio

Monroe, Michigan, Custer’s childhood home, unveiled the George Armstrong Custer Equestrian Monument in 1910

- Counties are named in Custer’s honor in six states: Colorado, Idaho (which is named for the General Custer Mine, which was named for Custer), Montana, Nebraska, Ok

lahoma, and South Dakota. - Townships in Michigan and Minnesota were named for Custer.

- Other municipalities named after Custer include the villages of Custer, Michigan and Custar, Ohio; the city of Custer, South Dakota; and the unincorporated town of Custer, Wisconsin.

- Custer National Cemetery is within Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument, the site of Custer’s death.

- The George Armstrong Custer Equestrian Monument of Custer, by Edward Clark Potter, was erected in Monroe, Michigan, Custer’s boyhood home, in 1910.

- Fort Custer National Military Reservation, near Augusta, Michigan, was built in 1917 on 130 parcels of land, as part of the military mobilization for World War I. During the war, some 90,000 troops passed through Camp Custer.

- The establishment of Fort Custer National Cemetery (originally Fort Custer Post Cemetery) took place on September 18, 1943, with the first interment. On Memorial Day 1982, more than 33 years after the first resolution had been introduced in Congress, impressive ceremonies marked the official opening of the cemetery.[111]

- Custer Hill is the main troop billeting area at Fort Riley, Kansas. Custer’s 1866 residence on the post has been preserved and is currently maintained as the Custer House Museum and meeting space (also sometimes referred to as Custer Home).

- The 85th Infantry Division was nicknamed The Custer Division.

- The Black Hills of South Dakota is full of evidence of Custer, with a county, town, and Custer State Park all located in the area.

- A prominent mountain peak in the Black Hills bears his name.[citation needed]

- The Custer house at Fort Abraham Lincoln, near present-day Mandan, North Dakota, has been reconstructed as it was in Custer’s day, along with the soldiers’ barracks, block houses, etc. Annual re-enactments are held of Custer’s 7th Cavalry’s leaving for the Little Bighorn.[112]

- On July 2, 2008, a marble monument to Brigadier General Custer was dedicated at the site of the 1863 Civil War Battle of Hunterstown, in Adams County, Pennsylvania.

- Custer Monument at the United States Military Academy was first unveiled in 1879. It now stands next to his grave in the West Point Cemetery.

Miscellany[edit]

In addition to “Autie” Custer acquired a number of nicknames. During the Civil War, after his promotion to become the youngest Brigadier General in the Army at age 23, the press frequently called him “The Boy General”. During his years on the Great Plains in the American Indian Wars, his troopers often referred to him with grudging admiration as “Iron Butt” and “Hard Ass” for his physical stamina in the saddle and his strict discipline, as well as with the more derisive “Ringlets” for his long, curling blond hair.[113]

Custer was quite fastidious in his grooming. Early in their marriage, Libbie wrote, “He brushes his teeth after every meal. I always laugh at him for it, also for washing his hands so frequently.”[114]

He was 5’11” tall, wore a size 38 jacket and size 9C boots.[115] At various times he weighed between 143 pounds (at the end of the 1869 Kansas campaign)[116] to a muscular 170 pounds. A splendid horseman, “Custer mounted was an inspiration.”.[117] He was quite fit: able to jump to a standing position from lying flat on his back! He was a ‘power sleeper: able to get by on very short naps after falling asleep immediately on lying down.[118] He “had a habit of throwing himself prone on the grass for a few minutes’ rest and resembled a human island, entirely surrounded by crowding, panting dogs.”[119]

Throughout his travels, he gathered geological specimens, sending them to the University of Michigan. On September 10, 1873, he wrote Libbie, “the Indian battles hindered the collecting, while in that immediate region it was unsafe to go far from the command….”[120]

He was well-liked by his native scouts, whose company he enjoyed. He often ate with them. A May 21, 1876 diary entry by Kellogg records, ‘General Custer visits scouts; much at home amongst them.”[121]

Before leaving the steamer Far West for the final leg of the journey, Custer wrote all night. His Orderly, John Burkman stood guard in front of his tent and on the morning of June 22, 1876, found him ‘hunched over on the cot, just his coat and his boots off, and the pen still in his hand.[122]

During his service in Kentucky, Custer bought several thoroughbred horses. He took two on his last campaign, Vic (for Victory) and Dandy. During the march he changed horses every three hours.[123] He rode Vic into his last battle.

Custer took his two staghounds- Tuck and Bleuch- with him during the last expedition. He left them with his orderly, John Burkman, when he rode forward into battle. Burkman joined the packtrain. He regretted not accompanying Custer, but lived until 1925, when he took his own life.[124]

The common media image of Custer’s appearance at the Last Stand- buckskin coat and long, curly blonde hair- is wrong. Although he and several other officers wore buckskin coats on the expedition, they took them off and packed them away because it was so hot. According to Soldier, an Arikara scout, “Custer took off his buckskin coat and tied it behind his saddle.”[125] Further, Custer- whose hair was thinning- joined a similarly balding Lieutenant Varnum and “had the clippers run over their heads” before leaving Fort Lincoln.[126]

Dates of rank[edit]

| Insignia | Rank | Date | Component |

|---|---|---|---|

| None | Cadet | 1 July 1857 | United States Military Academy |

| Second Lieutenant | 24 June 1861 | Regular Army | |

| Captain | 5 June 1862 | Temporary aide de camp | |

| First Lieutenant | 17 July 1862 | Regular Army | |

| Brigadier General | 29 June 1863 | Volunteers | |

| Brevet Major | 3 July 1863 | Regular Army | |

| Captain | 8 May 1864 | Regular Army | |

| Brevet Lieutenant Colonel | 11 May 1864 | Regular Army | |

| Brevet Colonel | 19 September 1864 | Regular Army | |

| Brevet Brigadier general | 13 March 1865 | Regular Army | |

| Brevet Major General | 13 March 1865 | Regular Army | |

| Major General | 15 April 1865 | Volunteers (Mustered out on 1 February 1866.) | |

| Lieutenant Colonel | 28 July 1866 | Regular Army |