Sword

A sword is a bladed weapon intended for slashing or thrusting that is longer than a knife or dagger. The precise definition of the term varies with the historical epoch or the geographical region under consideration. A sword consists of a long blade attached to a hilt. The blade can be straight or curved. Thrusting swords have a pointed tip on the blade, and tend to be straighter; slashing swords have sharpened cutting edge on one or both sides of the blade, and are more likely to be curved. Many swords are designed for both thrusting and slashing.

Historically, the sword developed in the Bronze Age, evolving from the dagger; the earliest specimens date to about 1600 BC. The later Iron Age sword remained fairly short and without a crossguard. The spatha, as it developed in the Late Roman army, became the predecessor of the European sword of the Middle Ages, at first adopted as the Migration period sword, and only in the High Middle Ages, developed into the classical arming sword with crossguard. The word swordcontinues the Old English, sweord.[1]

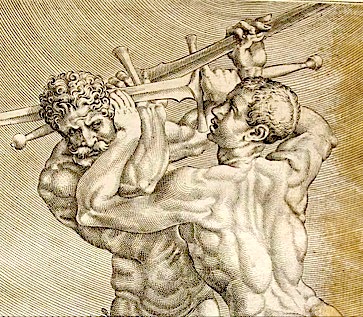

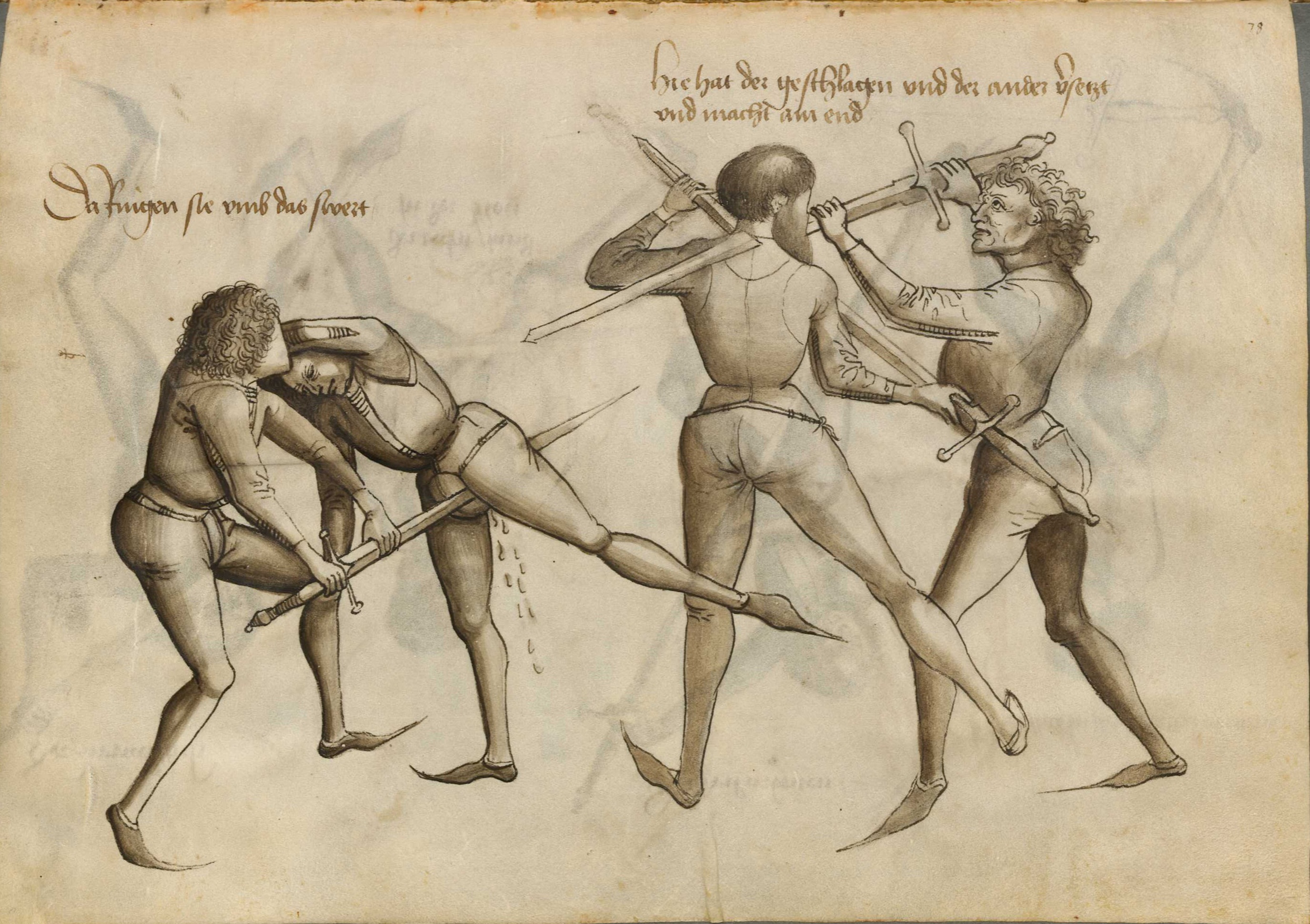

The use of a sword is known as swordsmanship or (in an early modern or modern context) as fencing. In the Early Modern period, western sword design diverged into roughly two forms, the thrusting swords and the sabers.

The thrusting swords such as the rapier and eventually the smallsword were designed to impale their targets quickly and inflict deep stab wounds. Their long and straight yet light and well balanced design made them highly maneuverable and deadly in a duel but fairly ineffective when used in a slashing or chopping motion. A well aimed lunge and thrust could end a fight in seconds with just the sword’s point, leading to the development of a fighting style which closely resembles modern fencing.

The saber (sabre) and similar blades such as the cutlass were built more heavily and were more typically used in warfare. Built for slashing and chopping at multiple enemies, often from horseback, the saber’s long curved blade and slightly forward weight balance gave it a deadly character all its own on the battlefield. Most sabers also had sharp points and double edged blades, making them capable of piercing soldier after soldier in a cavalry charge. Sabers continued to see battlefield use until the early 20th century. The US Navy kept tens of thousands of sturdy cutlasses in their armory well into World War II and many were issued to marines in the Pacific as jungle machetes.

Non-European weapons called “sword” include single-edged weapons such as the Middle Eastern scimitar, the Chinese dao and the related Japanese katana. The Chinese jian is an example of a non-European double-edged sword, like the European models derived from the double-edged Iron Age sword.

Contents

[hide]

History[edit]

Ancient history[edit]

The first weapons that can be described as “swords” date to around 3300 BC. They have been found in Arslantepe, Turkey, are made from arsenical bronze, and are about 60 cm (24 in) long.[2][3] Some of them are inlaid with silver.

Bronze Age[edit]

The sword developed from the knife or dagger. A knife is unlike a dagger in that a knife has only one cutting surface, while a dagger has two cutting surfaces. when the construction of longer blades became possible, from the late 3rd millennium BC in the Middle East, first in arsenic copper, then in tin-bronze.

Blades longer than 60 cm (24 in) were rare and not practical until the late Bronze Age because the tensile strength of bronze is relatively low, and consequently longer blades would bend easily. The development of the sword out of the dagger was gradual; the first weapons that can be classified as swords without any ambiguity are those found in Minoan Crete, dated to about 1700 BC, reaching a total length of more than 100 cm. These are the “type A” swords of the Aegean Bronze Age.

One of the most important, and longest-lasting, types swords of the European Bronze Age was the Naue II type (named for Julius Naue who first described them), also known as Griffzungenschwert (lit. “grip-tongue sword”). This type first appears in c. the 13th century BC in Northern Italy (or a general Urnfield background), and survives well into the Iron Age, with a life-span of about seven centuries. During its lifetime, metallurgy changed from bronze to iron, but not its basic design.

Naue II swords were exported from Europe to the Aegean, and as far afield as Ugarit, beginning about 1200 BC, i.e. just a few decades before the final collapse of the palace cultures in the Bronze Age collapse.[4] Naue II swords could be as long as 85 cm, but most specimens fall into the 60 to 70 cm range. Robert Drews linked the Naue Type II Swords, which spread from Southern Europe into the Mediterranean, with the Bronze Age collapse.[5] Naue II swords, along with Nordic full-hilted swords, were made with functionality and aesthetics in mind. [6]The hilts of these swords were beautifully crafted and often contained false rivets in order to make the sword more visually appealing. Swords coming from northern Denmark and northern Germany usually contained three or more fake rivets in the hilt.[7]

Sword production in China is attested from the Bronze Age Shang Dynasty.[8] The technology for bronze swords reached its high point during the Warring States period and Qin Dynasty. Amongst the Warring States period swords, some unique technologies were used, such as casting high tin edges over softer, lower tin cores, or the application of diamond shaped patterns on the blade (see sword of Goujian). Also unique for Chinese bronzes is the consistent use of high tin bronze (17–21% tin) which is very hard and breaks if stressed too far, whereas other cultures preferred lower tin bronze (usually 10%), which bends if stressed too far. Although iron swords were made alongside bronze, it was not until the early Han period that iron completely replaced bronze.[9]

In South Asia earliest available Bronze age swords of copper were discovered in the Harappan sites, in present-day Pakistan, and date back to 2300 BC[citation needed]. Swords have been recovered in archaeological findings throughout the Ganges–JamunaDoab region of India, consisting of bronze but more commonly copper.[10] Diverse specimens have been discovered in Fatehgarh, where there are several varieties of hilt.[10] These swords have been variously dated to times between 1700–1400 BC, but were probably used more notably in the opening centuries of the 1st millennium BC.[10]

Iron Age[edit]

Iron became increasingly common from the 13th century B.C. Before that the use of swords was less frequent. The iron was not quench-hardened although often containing sufficient carbon, but work-hardened like bronze by hammering. This made them comparable or only slightly better in terms of strength and hardness to bronze swords. They could still bend during use rather than spring back into shape. But the easier production, and the better availability of the raw material for the first time permitted the equipment of entire armies with metal weapons, though Bronze Age Egyptian armies were sometimes fully equipped with bronze weapons.[11]

Ancient swords are often found at burial sites. The sword was often placed on the right side of the corpse. However, there are exceptions to this. A lot of times the sword was kept over the corpse. In many late Iron Age graves, the sword and the scabbard were bent at 180 degrees. It was known as killing the sword. Thus they might have considered swords as the most potent and powerful object.[12]

Greco-Roman antiquity[edit]

By the time of Classical Antiquity and the Parthian and Sassanid Empires in Iran, iron swords were common. The Greek xiphos and the Roman gladius are typical examples of the type, measuring some 60 to 70 cm (24 to 28 in).[13][14] The late Roman Empire introduced the longer spatha[15] (the term for its wielder, spatharius, became a court rank in Constantinople), and from this time, the term longsword is applied to swords comparatively long for their respective periods.[16]

Swords from the Parthian and Sassanian Empires were quite long, the blades on some late Sassanian swords being just under a metre long.

Swords were also used to administer various physical punishments, such as non-surgical amputation or capital punishment by decapitation. The use of a sword, an honourable weapon, was regarded in Europe since Roman times as a privilege reserved for the nobility and the upper classes.[17]

The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea mentions swords of Indian iron and steel being exported from India to Greece.[18]Sri Lankan and Indian Blades made of Damascus steel also found their way into Persia.[18]

Persian antiquity[edit]

In the first millennium BC the Persian armies used a sword that was originally of Scythian design called the akinaka (acinaces). However, the great conquests of the Persians made the sword more famous as a Persian weapon, to the extent that the true nature of the weapon has been lost somewhat as the name Akinaka has been used to refer to whichever form of sword the Persian army favoured at the time.

It is widely believed that the original akinaka was a 14 to 18 inch double-edged sword. The design was not uniform and in fact identification is made more on the nature of the scabbard than the weapon itself; the scabbard usually has a large, decorative mount allowing it to be suspended from a belt on the wearer’s right side. Because of this, it is assumed that the sword was intended to be drawn with the blade pointing downwards ready for surprise stabbing attacks.

In the 12th century, the Seljuq dynasty had introduced the curved shamshir to Persia, and this was in extensive use by the early 16th century.

Chinese antiquity[edit]

Chinese steel swords made their first appearance in the later part of the Western Zhou Dynasty, but were not widely used until the 3rd century BC Han Dynasty.[9] The Chinese Dao (刀 pinyin dāo) is single-edged, sometimes translated as sabre or broadsword, and the Jian (劍or剑 pinyin jiàn) is double-edged. The zhanmadao (literally “horse chopping sword”), an extremely long, anti-cavalry sword from the Song dynasty era.

Middle Ages[edit]

Europe[edit]

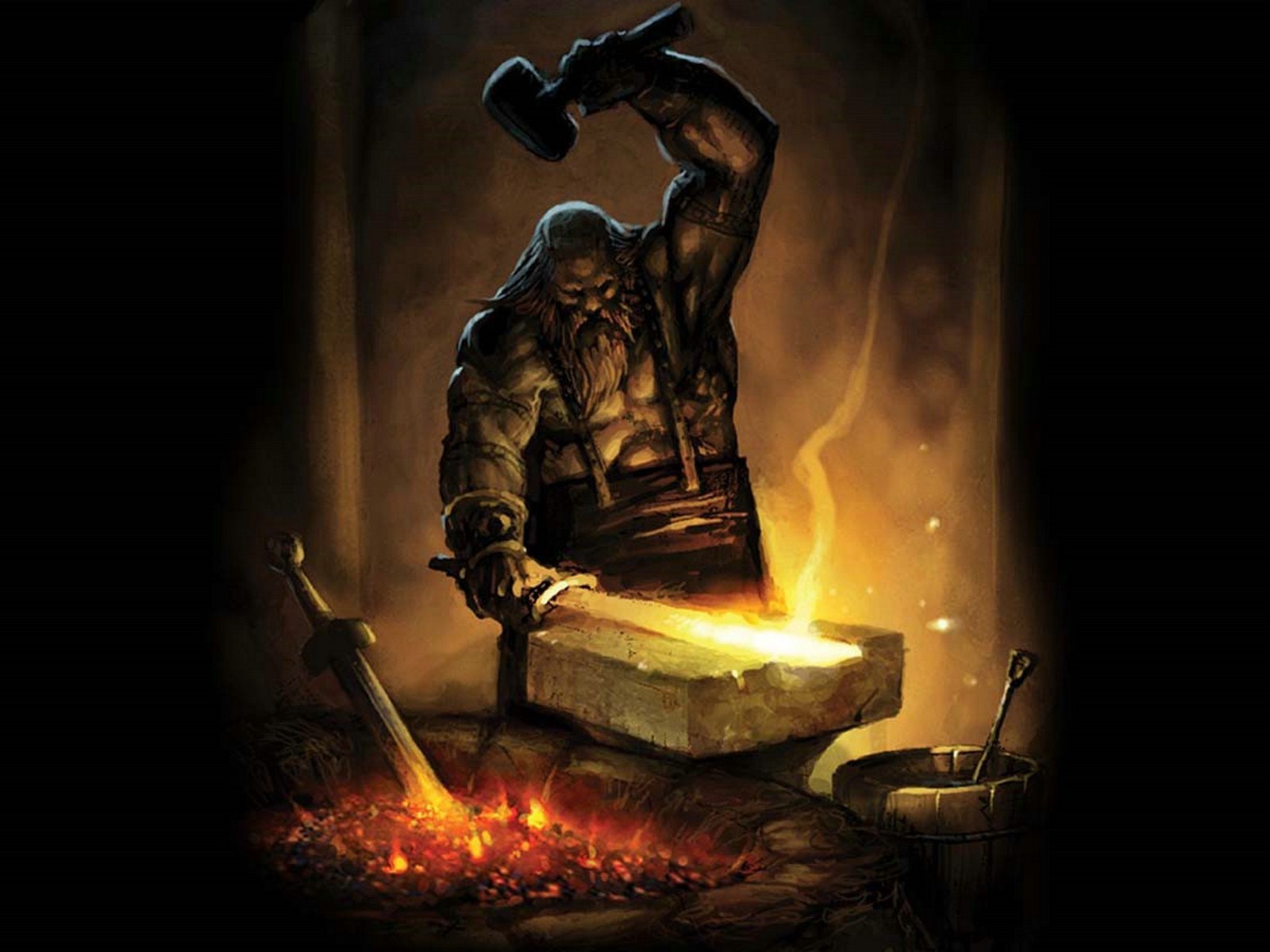

During the Middle Ages sword technology improved, and the sword became a very advanced weapon. It was frequently used by men in battle, particularly during an attack. The spatha type remained popular throughout the Migration period and well into the Middle Ages. Vendel Age spathas were decorated with Germanic artwork (not unlike the Germanic bracteates fashioned after Roman coins). The Viking Agesaw again a more standardized production, but the basic design remained indebted to the spatha.[19]

Around the 10th century, the use of properly quenched hardened and tempered steel started to become much more common than in previous periods. The Frankish ‘Ulfberht‘ blades (the name of the maker inlaid in the blade) were of particularly consistent high quality.[20]Charles the Bald tried to prohibit the export of these swords, as they were used by Vikings in raids against the Franks.

Wootz steel which is also known as Damascus steel was a unique and highly prized steel developed on the Indian subcontinent as early as the 5th century BC. Its properties were unique due to the special smelting and reworking of the steel creating networks of iron carbides described as a globular cementite in a matrix of pearlite. The use of Damascus steel in swords became extremely popular in the 16th and 17th centuries.[nb 1][21]

It was only from the 11th century that Norman swords began to develop the crossguard (quillons). During the Crusades of the 12th to 13th century, this cruciform type of arming sword remained essentially stable, with variations mainly concerning the shape of the pommel. These swords were designed as cutting weapons, although effective points were becoming common to counter improvements in armour, especially the 14th-century change from mail to plate armour.[22]

It was during the 14th century, with the growing use of more advanced armour, that the hand and a half sword, also known as a “bastard sword“, came into being. It had an extended grip that meant it could be used with either one or two hands. Though these swords did not provide a full two-hand grip they allowed their wielders to hold a shield or parrying dagger in their off hand, or to use it as a two-handed sword for a more powerful blow.[23]

In the Middle Ages, the sword was often used as a symbol of the word of God. The names given to many swords in mythology, literature, and history reflected the high prestige of the weapon and the wealth of the owner.[24]

Greater Middle East[edit]

The earliest evidence of curved swords, or scimitars (and other regional variants as the Arabiansaif, the Persianshamshirand the Turkickilij) is from the 9th century, when it was used among soldiers in the Khurasan region of Persia.[25]

East Asia[edit]

As steel technology improved, single-edged weapons became popular throughout Asia. Derived from the ChineseJian or dao, the Koreanhwandudaedo are known from the early medieval Three Kingdoms. Production of the Japanesetachi, a precursor to the katana, is recorded from ca. 900 AD (see Japanese sword).[26]

Japan was famous for the swords it forged in the early 13th century for the class of warrior-nobility known as the Samurai. The types of swords used by the Samurai included the ōdachi (extra long field sword), tachi (long cavalry sword), katana(long sword), and wakizashi (shorter companion sword for katana). Japanese swords that pre-date the rise of the samurai caste include the tsurugi (straight double-edged blade) and chokutō (straight one-edged blade).[27] Japanese swordmaking reached the height of its development in the 15th and 16th centuries, when samurai increasingly found a need for a sword to use in closer quarters, leading to the creation of the modern katana.[28]

Western historians have said that Japanese katana were among the finest cutting weapons in world military history.[29][30][31]

Indian Subcontinent[edit]

Khanda is a double-edge straight sword. It is often featured in religious iconography, theatre and art depicting the ancient history of India. Some communities venerate the weapon as a symbol of Shiva. It is a common weapon in the martial arts in the Indian subcontinent.[32] Khanda often appears in Hindu, Buddhist and Sikh scriptures and art.[33] In Sri Lanka, a unique wind furnace was used to produce the high quality steel. This gave the blade a very hard cutting edge and beautiful patterns. For these reasons it became a very popular trading material.[34]

…

[Message clipped] View entire message

|

Sep 25 (8 days ago)

|

|

||

|

||||

Preview YouTube video The Duellists (1977) – First duel with sabres

Preview YouTube video the duellists (1977) – third duel

Preview YouTube video The Deluge Duel.wmv

Preview YouTube video Inside the World of Longsword Fighting | The New York Times

Preview YouTube video The Greatest Japanese Movie Sword Fight EVER!

Preview YouTube video Sword Fighting As It Was For the Vikings