Category: The Green Machine

Here’s What You Need to Know: The M60 has come a long way from its Vietnam-era iteration.

The M60 is one of the enduring symbols of the American firearms industry. Born out of a fusion of two WWII-era German designs, the original M60 had several engineering flaws that lead to its replacement by the M240. But in 2014, Denmark adopted the M60E6 as the standard light machine gun of its armed forces, and the design continues to be manufactured and sold today. How did the M60 go from its rushed original design to the gun it is today?

The story of the M60 begins right after the end of WWII. During WWII, U.S. soldiers faced down the advanced MG42 machine gun and FG42 automatic rifle. While some may say the MG42’s rate of fire was too high, the weapon was far more suitable for infantry use than the American M1919A6, with superior ergonomics and lower weight. They also faced the FG42, an advanced box-fed automatic rifle that was lighter and more flexible than the American M1918A2 BAR.

Both of these weapons impressed American evaluators, who ordered Saginaw Steering Gear Division of General Motors to produce a version of the MG42 in the American .30-06 caliber. This did not go so well, with many engineering errors such as making the receiver too short. The final gun was highly unreliable, and the project was canned.

The U.S. Ordnance Corps then investigated the possibility of converting the FG42 into a belt-fed machine gun. A variety of prototypes were made. The T44 was a relatively standard FG42 converted to use the MG42’s belt feed, but the basic FG42 barrel proved too light for sustained automatic fire. The T52 came later, incorporating a heavier barrel. Later iterations of the T52 added a quick-change barrel and a new gas system.

The Army also began development of the T161 around this time, which was a variation on the T52 design, but modified for mass production. The T161 and T52 competed with each other throughout 1953 and 1954. In 1954, both guns were adapted for the new 7.62x51mm NATO round and M13 belt link, though they were not called that at the time. The T161 eventually won and went through several iterations before its final field trials as the T161E3 in 1955 and 1956.

The results of the T161E3 trials were impressive. Soldiers preferred the gun over the M1919-series of guns as it was far easier to maneuver, aim, move, and maintain. The gun weighed almost ten pounds less than the M1919A6, tipping the scales at around twenty-three pounds. The T161E3 was adopted as the M60 on 30 January 1957.

The M60 would see its first combat use in the Vietnam War in 1965 with the U.S. Marines. While it served well for many soldiers, providing heavy, accurate firepower, it also revealed many more flaws in the design.

In the door gunner role, M60s could fire upwards of 5000 rounds a day, laying down constant suppressing fire onto landing zones before helicopters came in. This caused the lightweight receivers to stretch and even crack, and gages were issued to armorers to determine when replacement should occur, which usually happened around 100,000 rounds or so. In contrast, the heavier M240 has been known to go for upwards of two million rounds without receiver repair.

The M60 feed tray could also not be closed with the bolt forwards, as this would bend parts within the belt feeding mechanism. The trigger group was also held by two pins held in with a flat spring. The plate could walk off, resulting in the trigger group falling off, sometimes resulting in a runaway gun. The gas system also tended to unthread itself. The problems with the trigger group and gas system were often rectified by wire tying the pieces into place but reflect poorly on the general state of the design.

Another big problem was with the quick change barrel. Since the bipod was on the barrel on the original M60, replacing the barrel meant the gun had to be dismounted from a firing position, maneuvered into a position to accept a fresh barrel, and remounted. This was far harder than the original MG42 barrel change.

The first attempt at fixing these problems was the M60E1, which added a cam to the feed tray cover to allow for it to be closed on a forward bolt. It also moved the bipod to the gas cylinder. However, this variant was not adopted.

Saco Defense, a large contractor for the U.S. military began resolving some of these issues in the 1980s with the M60E3 upgrade. It moved the bipod to the front handguard to resolved the barrel change issue and incorporated the cam from the M60E1. It also improved the gas system to increase reliability.

Unfortunately for Saco, the M240 had already been chosen to replace the problematic original M60s by this time, despite being heavier. However, special units like U.S. Navy Special Warfare (NSW) were still interested in the M60 due to its lighter weight. They adopted a further shortened version of the M60E3 as the M60E4 in the 1990s as the Mk43 Mod 0.

By the early 2000s, NSW began moving from the Mk43 Mod 0 to the Mk48, a version of FN Minimi chambered in 7.62 NATO, signaling the end of the M60.

However, U.S. Ordnance, a corporation founded in 1997 in Nevada, no relation to the U.S. Ordnance Corps mentioned earlier began work on a further upgrade to the M60 called the M60E6. U.S. Ordnance had been a contractor on the Mk43 Mod 0 project and thus was familiar with the M60 and what improvements it still needed.

Steve Heltzer, U.S. Ordnance’s Sales and Marketing vice president, lays out almost all of the upgrades of the M60E6 in a comment on Soldier Systems Daily.

Like the M60E1, E3, and E4 before it, the top cover can be closed with the bolt in the forward position. But on the M60E6 the feed mechanism is improved for additional “pull strength” to allow for better feeding when there is resistance on the belt.

Earlier problems with the retention of parts and parts walking out were all fixed via redesigns. Interestingly, the bipod is further updated from the M60E3 design to be stronger, simpler, and provide for better traverse when mounted.

The old problem of the M60 where different rear sight zeros were required for different barrels is resolved by adding an adjustable front sight on the barrel. The flash hider is also redesigned for better efficiency. Finally, the M60E6 adds rails to allow for the mounting of optics and lasers.

The result is a gun that’s highly competitive with the latest machine guns on the market. In independent torture testing by Dan Shea of Small Arms Defense Review, the M60E6 averaged around 8,300 mean rounds between failures, a figure better than the M60E4 or M240 during 1994 Army tests.

All of these probably resulted in the selection of the M60E6 by the Royal Danish Army in 2014. What made it competitive over competing LMGs? Probably the weight. The M60E6 is one of the lightest belt-fed light machine guns in its caliber, weighing only 9.35 kg. H&K’s competing MG5, said to be the runner-up in the trials, weighs 11.60 kg.

Does this mean that the M60E6 is the best light machine gun on the market currently? Hard to say. The FN Minimi 7.62 Mk3 is lighter at 8.8 kg, but the M60E6 holds the advantage of being cheaper for existing M60 users, as it can be purchased as a conversion kit. Either way, the M60 has come a long way from its Vietnam-era iteration.

Charlie Gao studied political and computer science at Grinnell College and is a frequent commentator on defense and national-security issues.

79 years ago – The 28th Infantry Division at the Battle of the Bulge

What sort of legacy might we leave once we’re gone? Some folks become unduly fixated on that subject. Not meaning to seem ghoulish, but some of that is dependent upon the circumstances surrounding one’s demise. For me, I just hope it isn’t anything terribly stupid.

As a soldier, gun writer and professional adventurer, I have invested a lifetime exploring the diaphanous frontier that demarcates normal life from that Really Bright Light. But were it not for the intervention of one epically overworked guardian angel, I might have inadvertently tipped over the edge. One of the more compelling episodes occurred back in the nineties in the skies over Oklahoma.

I have been rightfully described as the luckiest man alive. I cannot take issue with that. God has indeed blessed me well beyond my deserving. One handy example was a certain remarkable period in my Army aviation career.

It was scout pilot nirvana. We had four OH58 aeroscout helicopters and but two rated 58 drivers. We were therefore tasked to fly off our flying hour program lest we lose it for the next fiscal year. That meant my buddy and I got keys and a gas card several days a week with the directive to go forth and transform JP8 jet fuel into noise. If you were paying taxes during that time, sincerely and from my heart, thank you.

Flying an OH58 single-pilot with the doors off is much like driving a high-performance three-dimensional motorcycle. To unleash a 24-year-old American male on such a machine is the chemical formula for mischief. Don’t tell anybody, but I once flew from Fort Sill, Oklahoma, to Fort Chaffee, Arkansas, without climbing above 100 feet.

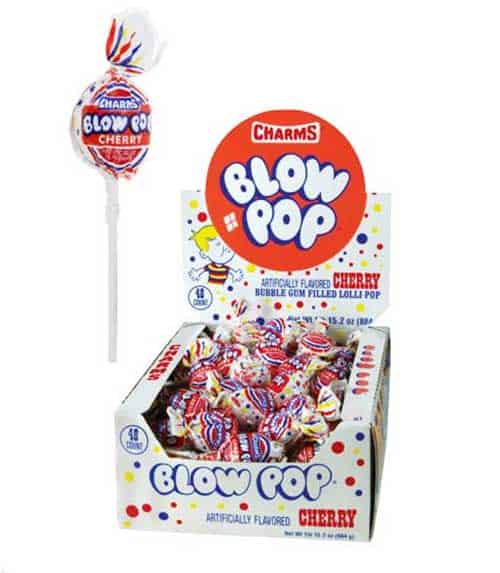

I became a connoisseur of all the greasy spoons across Oklahoma. My perennial favorite was Big Bob’s Bar-B-Q in Ada. I could land at the local airport and grab lunch while my airplane was being refueled. An extra fifteen cents at checkout landed me a Blow Pop for the trip home. Once I got to altitude I’d start sucking on that rascal.

Eventually I’d get sufficiently far along in the process to free the cardboard stick. This I discarded into the slipstream. It was biodegradable, so there was minimal guilt. The value-added portion of the timeless Charms Blow Pop is the chewing gum center. On this fateful day I was in the zone and living large.

I pulled my mike boom away from my lips far enough to accommodate and, without conscious thought, began to blow bubbles. As fate would have it perhaps ten minutes out from the Fort Sill restricted area the unthinkable happened. An unexpected gust of wind zipped in the open door and burst my bubble…all over my microphone.

Now understand this was a big deal. The OH58 won’t fly without two hands on the controls. Additionally, before I could get to the airfield I had to obtain clearance through range control. Fort Sill is the home of the Field Artillery. At all hours of the day and night the airspace above Fort Sill is simply alive with stuff that explodes. I only had so much gas remaining. This was not cool.

I tightened the friction lock down on the collective and pinched the cyclic stick between my knees. From an initial altitude of about three thousand feet I then started scraping madly at my mike boom in a frenetic effort to remove enough chewing gum to make the cursed thing work. As I did so, the aircraft would gradually attempt to roll inverted. When the attitude grew alarming I would seize the controls once again, stabilize the helicopter, and repeat my performance. Each time I subsequently called out to the range control guys I got no answer. I feared I was doomed.

Sometime after the first, “Unidentified aircraft approaching the restricted area, say intentions” radio call I finally got enough of the gooey stuff off to talk back. I then landed the aircraft uneventfully. However, I had gum in my hair, all over my Nomex gloves, plastered across the front of my flight helmet, and mashed into my eyebrows. When I went to the Central Issue Facility to swap out my gloves the following day I pre-emptively stated, “I really don’t want to talk about it.” The supply guys had mercy on me and didn’t press.

“Died in a fiery crash while scraping chewing gum off of his mike boom” would have looked pretty darn stupid engraved on a tombstone.

Since the Revolutionary War, U.S. officers have carried pistols. Since World War II, generals have been issued a different sidearm from most of the military they lead, and nowadays most officers will be issued a handgun, especially if they are in a combat role. These small and mostly decorative handguns are known as general officer’s pistols.

Since the Revolutionary War, U.S. officers have carried pistols. Since World War II, generals have been issued a different sidearm from most of the military they lead, and nowadays most officers will be issued a handgun, especially if they are in a combat role. These small and mostly decorative handguns are known as general officer’s pistols.

The Colt Model 1903 and 1908

Supply issues are always a problem when a nation goes to war and World War II was no different. In this case, it’s plenty believable that generals were issued firearms that were alternatives to the M1911 due to supply reasons.

The U.S. military began ordering the Colt M1903 and M1908 Pocket Hammerless Pistols and issuing the .380 ACP Colt Model of 1908. When those became hard to get, they moved to the Colt M1903 in .32 ACP.

These two pistols are identical outside of their calibers. They are simple blowback-operated handguns that are fed from a single-stack magazine. They were called Hammerless, but they, in fact, did have an internal single-action hammer. The pistols featured a manual safety that doubled as a slide lock. They were much smaller than the M1911 and easier to carry. Outside of being the first general officer’s pistols, they were also used by OSS Agents.

The M15

To replace the limited and aging stocks of Colt M1903 and M1908 pistols, the armory at Rock Island began producing the M15 general officer’s pistols. Manufacturing began in 1972 and the pistols remained in production until 1984. These firearms used the same ammunition, magazines, and design as the M1911, which simplified production, but had their barrel trimmed from five to 4.25 inches.

The sights of the pistol were also a fair bit larger and they featured wood grips with nameplates featuring the individual general’s name and the slides read General Officer’s Model RIA.

The military made 1,004 M15 pistols and allowed generals to purchase their pistol upon retirement. The creation of the M15 led to the popularity of more compact M1911 pistols.

The M9 GO

The M9 General Officer’s Pistols are identical to a standard M9 with two subtle differences.

First, they had a serial number that began with the prefix GO standing for General Officer. Second, they had a second pair of grips that would feature a nameplate with the general’s name.

The M9 GO broke the tradition of smaller guns for general officers.

Related: This Nazi night pistol might have been the first light-fitted pistol

The M18 GO

As the SIG M17 and M18 began replacing the standard M9, the general officer’s pistols followed suit. Generals used the smaller M18 pistol, but it’s still identical to the M18 series in use by several branches. Like the standard M18, these guns have a coyote finish with either tan or black controls.

The M18 GO series features the GO prefix for serial numbers, and officers were allowed to choose their serial numbers.

The general officer’s pistols

General officers carry guns unique to their role. These firearms tend to be incredibly rare and generals tend to keep them after retirement.

Issuing these guns is an American military tradition that will likely continue long after I’m gone.

Feature Image: Maj. Gen. David Blackledge, left, commanding general of U.S. Army Civil Affairs and Psychological Operations Command (Airborne) hands newly promoted Brig. Gen. Ed Burley his custom Beretta M9 pistol. (DVIDS/352nd Civil Affairs Command)