The U.S. Army’s latest multi-billion-dollar, high-tech small arms program is moving forward and, and it represents nothing less than an entirely new direction in U.S. military small arms development.

In April of last year, the Army announced that it had selected the winners of the Next Generation Squad Weapon (NGSW) competition: an infantry rifle and a light machine gun, along with a new cartridge and optical system that the pair would share. The news sent shock waves through the firearm and defense communities.

“We should know that this is the first time in our lifetime, the first time in 65 years, that the Army will field a new weapon system of this nature—a rifle, an automatic rifle, a fire-control system and a new caliber family of ammunition,” said Brig. Gen. Larry Burris, the Soldier Lethality Cross-Functional Team Director, at a press conference for the selection. Then, for emphasis, he added, “This is revolutionary.” For those of us in the civilian world, the announcement prompted questions about how and why our tax dollars are being spent.

The Problem

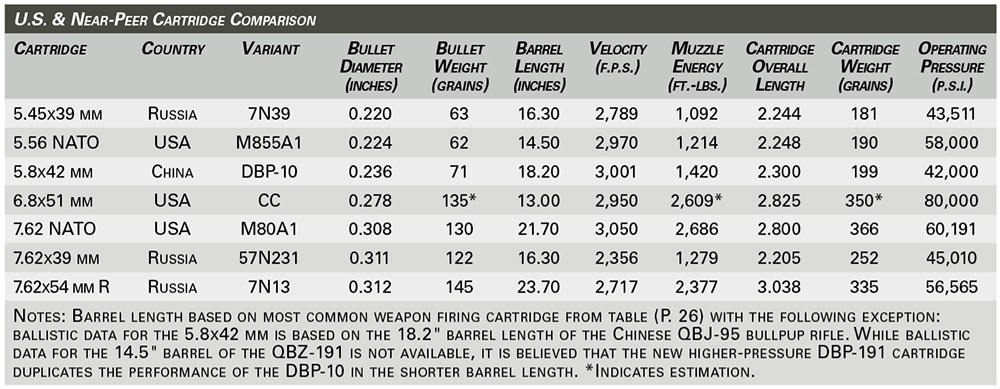

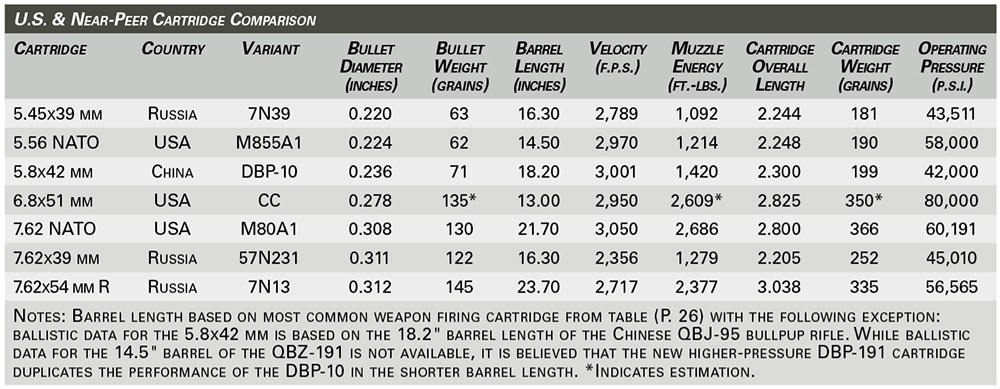

Two decades of constant combat usage of the U.S. military’s small arms have exposed some deficiencies in the current inventory. These include the effective range of the 5.56 NATO cartridge, the ability of M16-derived systems to deliver suppressive fire, the need for modularity to accommodate modern accessories and the weight that small arms systems add to an already-burdened soldier. The search for solutions to these problems are defined by a defense industry buzzword and a catchphrase: “overmatch” and “near-peer adversaries.” Overmatch is the ability to outperform the range, accuracy and lethality of the weapons used by the enemy of an advanced military with capabilities similar to those of the United States, such as Russia and China, and such militaries are seen as near-peer adversaries (see p. 26).

While the 5.56 NATO has a similar effective range to the Russian 5.45×39 mm and Chinese 5.8×42 mm cartridges (approximately 500 meters), that range would have to be extended for “overmatch.” Additionally, many arms that U.S. soldiers have often found themselves facing use the 7.62×54 mm R cartridge, as fired by PSL and SVD rifles and the PK series of medium machine guns, which have an effective range of approximately 800 meters.

Another factor determining the next cartridge’s performance is the fact that, during the past decade, ballistic body armor technology has improved and is less costly, making it possible for near-peer adversaries to equip their entire front-line forces with protection against conventional projectiles. Additionally, the U.S. military is increasingly encountering body armor in the hands of irregular forces and terrorists.

In 2017, retired Maj. Gen. Robert H. Scales stated the problem succinctly to the Senate Armed Services Committee: “Survival [on the modern battlefield] depends on the ability to deliver more killing power at longer ranges and with greater precision than the enemy.”

In response, the U.S. military has adopted limited numbers of extended-range specialty weapons, incrementally upgraded existing systems with “Product Improvement Programs” and improved ammunition with “Enhanced Performance Round” versions of both the 5.56 NATO and 7.62 NATO cartridges. But the limits of 75-year-old cartridge and arms designs have been reached. As Brig. Gen. William Boruff, Joint Program Executive Officer for Armaments and Ammunition, explained at the NGSW press conference, “the current 5.56 cartridge has been maxed out from the performance perspective.”

The three cartridges considered for the NGSW program are exemplified by (l. to r.): a cased telescoped round by Textron; a hybrid-case round by SIG Sauer; and a composite-case round by True Velocity. All three were designed to fire the same copper-jacketed 6.8 mm bullet.

The History

From the conclusion of World War II, the U.S. military has sought solutions for increased lethality, greater hit probability and a lighter combat load in its small arms. When the Army announced the NGSW program in 2018, those who were skeptical that the effort would ever result in a finalized and adopted system were justified in their doubt. When the M16 was adopted in the early 1960s, the Army was already in the midst of a “future weapons” program—the Special Purpose Individual Weapon (SPIW). The SPIW program was an extension of Project SALVO, which itself was the result of the Army’s post-World War II analysis of how small arms were used by infantrymen in combat.

Its conclusion, which had already been reached by the Germans during the war, was that the most effective arm for an infantryman to carry was a fully-automatic rifle that fired an intermediate cartridge. The result was a compromise between the light weight and high volume of fire afforded by a submachine gun chambered in a pistol cartridge and the range, accuracy and ballistic payload of a full-size battle rifle. The groundbreaking “Sturmgewehr” design was quickly matched post-war by the Soviet Kalashnikov, and the rest of the world was left scrambling to update their arsenals.

Project SALVO worked on the idea that hit probability was increased by the greater number of projectiles you could throw at a target, essentially making a rifle into a long-range shotgun. The search for a lightweight “Small Caliber, High Velocity” rifle led to the adoption of the M16. The SPIW program sought to develop an arm that combined a grenade launcher with a rifle firing small, arrow-like “flechette” projectiles. It was abandoned in the early 1970s, and the M16 soldiered on.

By 1972, the Army was also looking for an arm that could cover the ground between the M16 and the M60 with the Squad Automatic Weapons (SAW) program. The program centered upon a new SAW-specific cartridge firing a 135-grain 6 mm bullet that gave a ballistic performance between the 5.56 mm and the 7.62 mm. While the Army eventually adopted the FN Minimi as the M249, it stuck with using the 5.56 NATO cartridge.

Soon after the M16A2 was adopted, in 1986, the Army began the Advanced Combat Rifle (ACR) program, the goal of which was once again to produce an arm that would increase hit probability on the battlefield. Many of the innovations developed during the SPIW program were examined again, including flechette rounds, duplex projectile loads and burst fire, along with new innovations such as polymer-case telescoping ammunition, caseless molded-propellant cartridges and the advantages provided by sound suppression and optical sighting systems. As no ACR candidate could provide “an enhancement in hit probability of at least 100 percent at combat ranges” over the M16, the program was canceled.

By the 1990s, the newest effort to replace the M16 was the Objective Individual Combat Weapon (OICW) program. The resulting arm combined a 5.56 NATO-firing rifle and a semi-automatic grenade launcher with a computer-assisted sighting system firing air-burst munitions, but it did not result in a practical design. An offshoot of this program was the further development of the Heckler & Koch G36-derived XM8, which was also eventually canceled.

The search for more effective small arms continued into the 21st century. In 2004, the Lightweight Small Arms Technologies (LSAT) program was formed to investigate polymer-case and caseless ammunition technologies. The program also developed a light machine gun prototype to replace the M249. An Individual Carbine competition seeking a replacement for the M4 ran from 2010 to 2014, but it ended without selecting a replacement. Ditto for the Interim Combat Service Rifle program. The M16 and its derivatives, it seemed, were here to stay.

Since the adoption of the M16, the Army has sought a replacement. Pictured is testing of the XM8 prototype in the early 2000s.

The NGSW Competition

In many ways, the NGSW program was a ballistics-centric endeavor. Brigadier General Boruff summarized the purpose of the program when he stated it was, “all about energy on target and the longer ranges.” The Army knew the performance it wanted and sought an integrated system of a cartridge that provided those required ballistics, an arm to fire it and a sighting system that would give the average soldier the ability to utilize both to their maximum potential.

The Next Generation Squad Weapons program sought to select a new cartridge, a rifle (NGSW-R) and light machine gun or “automatic rifle” (NGSW-AR) to fire it and a “fire control” optical sighting system (NGSW-FC). Beginning in 2017, the requirements for the systems were announced. These stipulated the allowable size and weight of the new firearms and that they were to fire a cartridge of the submitting competitors’ own design that used a specific 6.8 mm bullet. The arm and cartridge combination were to be effective to 800+ meters. Initial competitors included Desert Tech, MARS/Cobalt Kinetic, FN America, General Dynamics, Textron and SIG Sauer.

The NGSW selection demonstrated a new process of developing, testing and adopting new technology with the Army’s use of “Cross-Functional Teams.” Each weapons system was given a “touch point” analysis by individual soldiers, with more than 1,000 soldiers providing 20,000 hours of feedback. In the Army’s estimation, the NGSW program condensed a process that would typically take eight to 10 years into 27 months.

In August 2019, the selection of three firearm finalists were announced. General Dynamics (its efforts were later taken over by Lonestar Future Weapons Systems) submitted a magazine-fed bullpup design for both the rifle and automatic rifle. The company partnered with Beretta for the design, which used the bullpup layout to incorporate a 20″ barrel in a firearm that would yield the ballistics the Army sought at a reasonable pressure, yet maintain an overall length less than the current M4. They partnered with True Velocity ammunition to develop a composite-case cartridge of conventional shape made of polymer and a steel base.

Textron, which had worked with the Army on its LSAT program, submitted a magazine-fed rifle and belt-fed automatic rifle of conventional layout. It partnered with H&K on the firearms’ designs, Winchester Ammunition on the ammunition and Lewis Machine & Tool for the suppressor. Its cartridge featured a “cased telescoped” design, meaning the entire bullet is contained inside a polymer case, which results in reduced weight and overall length.

The last candidates were submitted by SIG Sauer, which ultimately was awarded a 10-year, indefinite-delivery, indefinite-quantity contract capped at $4.7 billion. The initial phase is a $20.4 million dollar contract to provide 25 XM5s and 15 XM250s, along with ammunition, for further development. Eventually, the Army expects to procure 107,000 XM5 rifles and 13,000 XM250 automatic rifles. SIG’s submissions are described below; although note that the components of the NGSW program are still being developed, so the specifications and capabilities stated below are subject to change.

The XM250 automatic rifle feeds from a disintegrating-link belt (l.). The 6.8 mm Common Cartridge with its solid copper training/close-range bullet and its armor-piercing bullet (r.) was on display at the Association of the United States Army exposition in October 2022 in Washington, D.C.

The 6.8×51 mm Common Cartridge

As a result of several ballistics studies, the U.S. Army determined that a 6.8 mm-diameter (0.277 cal.) bullet with a weight of approximately 135 grains would be optimal for what it believes will be the conditions of the future battlefield. For the NGSW program, the Army produced a “General Purpose Projectile” that uses a hardened-steel penetrator with a copper jacket and core similar to the M855A1. It was provided to the competing manufacturers who were tasked with developing their own cartridge that used the projectile, met the Army’s ballistic requirements and weighed less than a 7.62 NATO cartridge.

The cartridge SIG developed for its winning NGSW firearms has been designated as the 6.8×51 mm Common Cartridge (CC). As can be inferred from the “51 mm” part of its designation, the cartridge’s case is the same length as the 7.62 NATO, necessitating an “AR-10”-size firearm platform. The case is almost the identical diameter as well, meaning that capacity in a box magazine is the same as the 7.62 NATO cartridge. While the Army hasn’t revealed the exact ballistic performance of the new cartridge, the 6.8 mm CC delivers more velocity than the M855A1 with a bullet more than twice as heavy. The Army claims that the new chambering is superior to both the 6.5 mm Creedmoor and 7.62 NATO at ranges up to 800 meters and that it can defeat Level III body armor with non-armor-piercing ammunition out to 600 meters.

The new cartridge is not to be confused with the 6.8 Remington SPC, another cartridge developed at the behest of the U.S. military. Designed in the early 2000s, the SPC has the same overall length as the 5.56 NATO, meaning that existing M4 and AR-15-type firearms could be adapted to use it.

Since defeating body armor comes down, in large part, to velocity, every effort was made to get the maximum performance out of the new cartridge. The result was a chambering that operates at very high pressure. The Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers’ Institute (SAAMI) specification for the cartridge is 80,000 p.s.i., or about 30 percent higher than the operating pressure of similar cartridges such as 7.62 NATO or 6.5 mm Creedmoor.

Three .277 Fury loads are currently offered for the civilian market: conventional brass cartridge cases loaded with a 135-grain FMJ or soft-point bullet and hybrid-case cartridges with a 150-grain polymer-tip bullet.

When SAAMI certified the .277 Fury, the civilian version of the 6.8 mm CC cartridge, it included the warning that the cartridge, when loaded to pressures greater than 68,000 p.s.i., would “require cartridge case and/or firearms design that depart from traditional practices.” This is exactly what SIG did, developing a “hybrid” metal case for the cartridge. As the unsupported portion of a brass cartridge case that protrudes from the rear of the chamber and the primer pocket cannot handle these pressures, the SIG design uses a stainless-steel case head married to a brass case body. SIG claims the hybrid case design allows for an additional 350 f.p.s. in velocity over a conventional brass case.

The brass and stainless-steel hybrid case of the NGSW 6.8 mm Common Cartridge is designed to handle its 80,000 p.s.i. pressure.

In addition to its strength, steel is lighter than brass, so using it in what is the thickest part of the cartridge case keeps the overall weight of the loaded cartridge down. Though being nominally the same overall size, 6.8 mm CC weighs less than a 7.62 NATO cartridge.

The commercial .277 Fury launches a 150-grain bullet at 2,830 f.p.s. from a 16″ barrel—or approximately the performance you’d expect from a .270 Win. fired from a 24″ barrel. SIG also makes a reduced-power version of the .277 Fury cartridge that uses a conventional all-brass case and presumably operates at less than 68,000 p.s.i. The Army likewise plans to use a reduced-power version of the cartridge for training purposes and close-range combat scenarios where overpenetration is a risk.

SIG Sauer will be producing all of the Army’s 6.8 mm ammunition, using projectiles supplied by the Lake City Army Ammunition Plant, for the next few years. Lake City (a government-owned plant run by private contractor Winchester Ammunition) is building a new facility dedicated solely to producing the 6.8 mm CC ammunition that should be online by 2025 or 2026. By 2030, Lake City will take over as the lead producer of 6.8 ammunition. Lake City’s production of 5.56 NATO and 7.62 NATO will continue at current rates in the near future.

Last year, SIG offered a limited run of MCX-Spear rifles for the civilian market in semi-automatic-only format.

XM5 Rifle

In many ways, SIG’s winning firearms were the most conventional NGSW choices. Its rifle prototype, adopted as the XM5, is based on the commercially available MCX, which combines features of the M16 with a short-stroke piston and recoil-spring system that mimics the AR-18. SIG had already scaled up the 5.56 mm MCX to AR-10 size to accommodate a .308 Win.-class cartridge with its MCX-MR, which was a competitor in the Army’s Compact Semi-Automatic Sniper System program.

The XM5’s controls are M16-style rendered bilaterally for full ambidextrous use. The magazine release, bolt release and safety selector are present on both sides of the rifle, along with a bilateral, AR-type, charging handle. Additionally, there is a second non-reciprocating charging handle positioned on the left side of the receiver. The rifle utilizes an M4-style forward-assist device and case deflector. While having a general M4 familiarity, the exterior of the XM5 is also updated. The aluminum-alloy handguard features M-Lok slots, and there are built-in push-button sling swivel sockets on the handguard and receiver.

The XM5 mechanism uses a multi-lug rotating bolt. Function is provided by a short-stroke gas piston with an adjustable gas regulator. The upper and lower receivers are made of aluminum alloy with steel inserts in high-wear locations. Because of the gas-piston design and recoil springs contained within the receiver, the XM5’s stock not only telescopes like an M4 but also folds to the left side, and the rifle can be fired with the stock folded. The barrel has a tapered heavy profile and is held in place by a clamping system that uses two Torx-head screws that allow it to be removed in the field. The rifle is supplied with a two-stage match trigger, uses SR-25-pattern magazines and is capable of both semi- and full-automatic fire.

The XM5 is designed to be used in conjunction with a suppressor. In 2021, the Marine Corps announced that it would be supplying all of its front-line personnel with suppressor-equipped arms, to both make communication on the battlefield easier and to prevent the long-term health effects of loud noise exposure, and the Army seems to be following that lead. The XM5’s suppressor is also made by SIG and is based on its SLX series developed for U.S. Special Operations. The backpressure that a suppressor adds to a firearm can result in increased gases directed back at the shooter. The XM5’s suppressor is engineered to have a “flow-through” design that yields “low toxic fume blowback,” and SIG claims that using the suppressor results in no additional gas being expelled through the rifle’s ejection port. The suppressor is mounted by threading onto the XM5’s muzzle device and is held in place with a locking ring. Due to suppressor usage, the XM5’s 13″ barrel keeps the conventionally laid out rifle as compact as possible. With the suppressor installed, the XM5’s overall length is 36″, and it weighs 9 lbs., 14 ozs. There is no provision for mounting a bayonet.

The XM250 is designed to be used with a suppressor. It feeds from 100-round disintegrating link belts housed in a polymer and canvas pouch that mounts below the receiver.

XM250 Automatic Rifle

SIG’s winning automatic rifle design is based on the company’s MG 338, a belt-fed .338 Norma Mag.-chambered machine gun designed for U.S. Special Operations. The XM250 is an air-cooled, belt-fed design that fires from an open bolt. The action is gas-operated with a short-stroke gas piston system and is capable of both semi-automatic and fully-automatic fire. Its rate of fire is between 650 and 750 rounds per minute, depending on the ammunition used.

While SIG has been tight-lipped about the internal features of the XM250, some design features can be inferred from details found in the company’s machine gun patent applications. The XM250 uses the recoil-mitigation system of its .338 big brother, where the rotating bolt operates within a “barrel extension” that is fixed to the barrel and recoils within the outer receiver, with the bolt and barrel extension using separate recoil springs. SIG claims the XM250’s felt recoil is less than an M4. Although the XM250’s 16″ barrel is quick-change with the rotation of a collar, unlike the M249 it is not designed to be swapped under combat conditions. The XM250’s barrel-retaining system makes it field-adaptable for other cartridges in the 7.62 NATO class.

The XM250 is fed from 100-round disintegrating-link belts. The belts are housed in a polymer and canvas box that attaches below the gun with a “mag well” connection. Belts can be loaded into the gun whether the bolt is forward or back, in either safe or fire mode and with the feed tray open or closed. Unlike the M249, there is no provision that allows for the use of a detachable box magazine. The XM250 uses a left-side charging handle and has bilateral safety selector switches.

On the top of its receiver and handguard, the XM250 has a full-length Picatinny rail. It uses a feed tray cover that opens to the side to allow for mounting of optical systems without interference when the feed tray is open. Designed to be used with optics, the XM250 also has a set of offset back-up iron sights. The handguard features M-Lok slots, and the XM250’s bipod is made out of titanium to further save weight. The buttstock telescopes to multiple positions to adjust length of pull.

The XM250 is designed to use the same suppressor system as the XM5. Despite its visual bulk, the XM250 with bipod and suppressor weighs 3 lbs., 8 ozs., less than the M249 and is 13 lbs. lighter than the 7.62 NATO M240B. The size and weight of the XM250, along with its ability to fire semi-automatically, suggest that it could be used as a “rifle” in close-quarters engagements or, when combined with the new magnified optic, as a more precise “Designated Marksman Rifle” at longer ranges.

Shown atop an XM5 rifle at the AUSA expo in October 2022 in Washington, D.C., the XM157 Fire Control System, produced by Vortex, is a 1-8X riflescope with electronics that can take into account factors such as wind, elevation, inclination and range.

XM157 Fire Control System

The competition for an optical sight, or “Fire Control System,” included submissions from Vortex Optics and L3Harris (the former parent company of EOTech). The winner was Vortex’s offering, which was designated as the XM157.

The Fire Control System is the part of the NGSW program that represents the most radical leap forward in technology and capability. At the heart of the XM157 “Smart Optic” is a conventional 1-8X LPVO (low power variable optic) riflescope with a 30 mm objective lens and etched reticle that can operate without battery power. The “smart” side of the XM157 is information that can be projected as a digital Active Reticle onto a see-through display in the scope’s first focal plane. This allows for a customizable display that can include such information as ballistic drop or wind holds. The system has a built-in laser rangefinder and can compute other environmental factors, such as temperature, elevation, inclination and declination. This information is computed in real time by a unit that sits on top of the main scope’s body and adjusts the digital reticle accordingly. In addition to the rangefinder laser, the unit also contains visible and infrared aiming lasers. Again, some hints at the system’s possible capabilities can be gleaned from recent Vortex patents, such as a system that would allow the optic to display the number of rounds remaining in the magazine of the arm to which it is attached or the ability to display a virtual target for dry-fire practice.

While the XM157 sounds complicated, its function is simple and user-friendly, with all functionality displays seen through the scope. The system has passed all mil-standard optics tests of temperature, water immersion, dust, drops, shock, etc., so it’s as rugged as it is high-tech.

The system is powered by two CR123A batteries that will power the unit for “weeks” according to Vortex. While the actual weight of the system has not been revealed, according to Vortex, it is less than the combination of a conventional LPVO and ballistic computing system (presumably less than 30 ozs.). The entire unit is “modular and upgradeable,” meaning that newer capabilities can be added in the future, such as “augmented reality” modes that will allow soldiers to tag target points and share them wirelessly to other soldiers’ optics systems.

The XM157 will be made entirely in America of U.S.-made components, including the lenses. Vortex is scheduled to supply 250,000 systems over the next decade at the cost of up to $2.7 billion. As is apparent from that quantity, the XM157 is intended to be used not only on NGSW weapons but also on “legacy” platforms, such as the M4.

The XM5 rifle weighs 9 lbs., 13 ozs. with its suppressor mounted. Though equipped with offset backup iron sights, it is intended to be used with the XM157 optic.

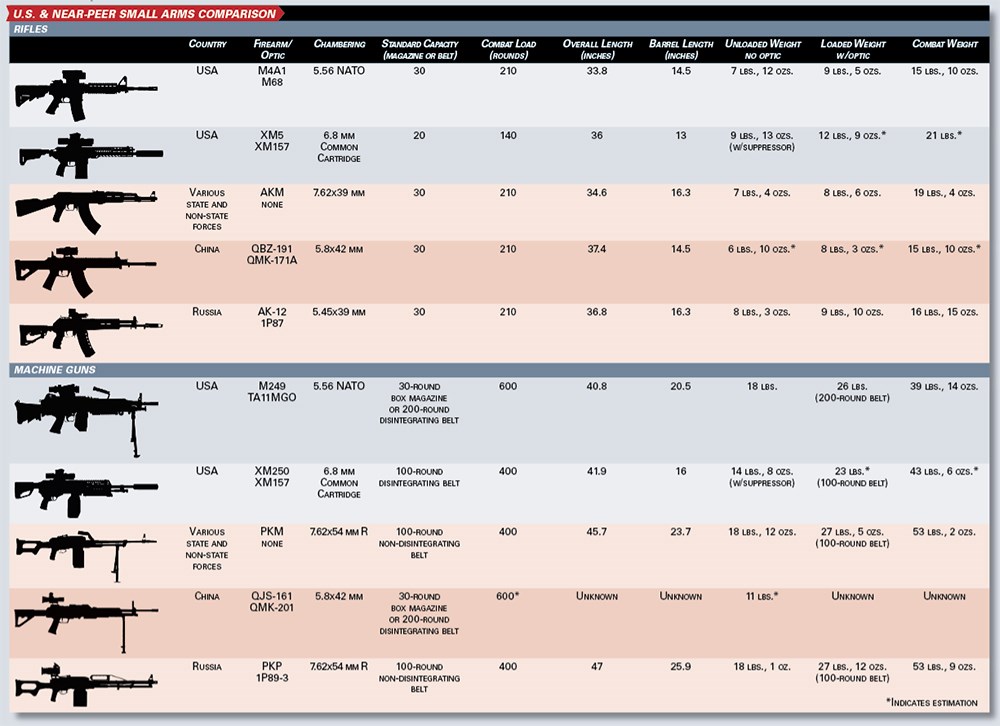

The Reaction

Expectedly, the announcement that the Army was replacing the rifle and cartridge combination that it has used for more than half a century was met with a swift reaction. One of the first criticisms involved weight. When it comes to physics, there’s no free lunch. The Army’s ballistic needs required a cartridge larger than the 5.56 NATO and a weapon larger than an M4 to fire it. A loaded XM5 with the XM157 optic will weigh about 3 lbs., 4 ozs., more than a loaded M4A1 with an M68 optic. With a full combat load, the XM250 outweighs the M249 by about 3 lbs., 8 ozs., while carrying 200 fewer rounds.

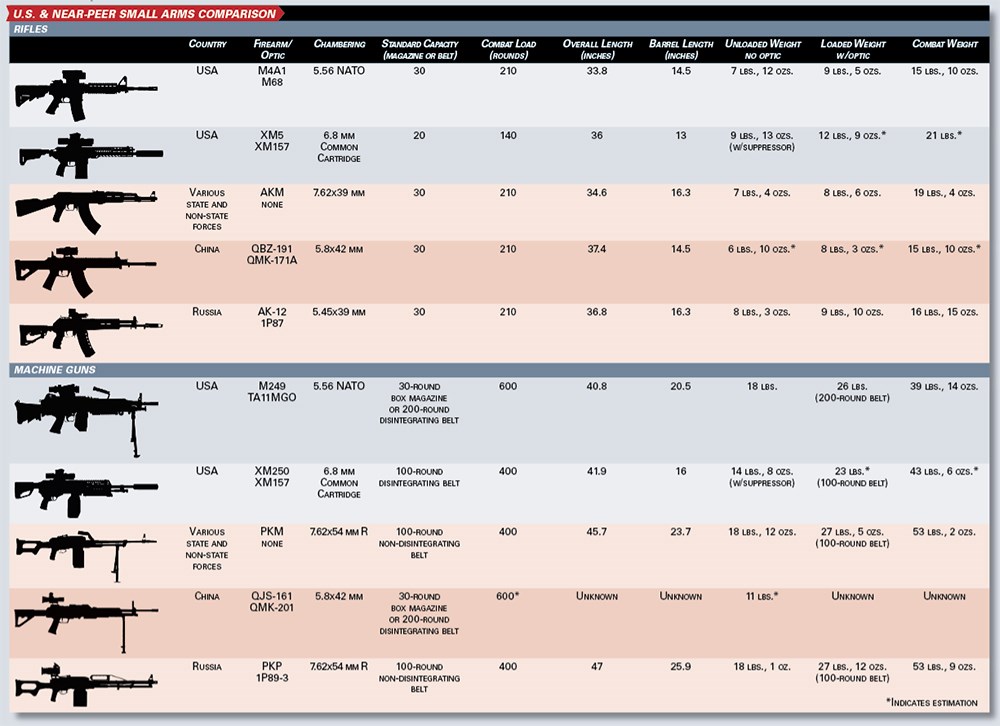

This brings up the second criticism of a decreased round count and increased weight for a combat load. The larger diameter of the 6.8 mm cartridge means fewer rounds can be stacked in a magazine of similar size to the current 30-round M4 magazine. According to the Army, the XM5 basic combat load is seven, 20-round magazines, which weighs 9 lbs., 13 ozs., in total. For the XM250, the basic combat load is four 100-round pouches at 27 lbs., 1 oz. For comparison, the M4 carbine combat load, which is seven 30-round magazines, weighs 7 lbs., 6 ozs., and the M249 combat load is three 200-round pouches weighing 20 lbs., 14 ozs., in total. This would result in a real-world total combat weight of 21 lbs. for the XM5 and 43 lbs., 6 ozs., for the XM250, versus 15 lbs., 10 ozs., for the M4 and 39 lbs., 14 ozs., for the M249.

Based on these two points, many critics bring up the specter of the M14, a large and powerful rifle designed for the plains of Germany that found itself in the jungles of Vietnam. But the counterpoint is that the Next Generation Squad Weapons signal a shift in the Army’s small arms doctrine. In a way, the NGSW program is the antithesis of the post-World War II Project SALVO. Increased weight and decreased round count suggests that the Army expects the NGSW weapons and optics system to allow soldiers to eliminate their targets at longer ranges with fewer rounds.

Trickle Down

Military innovation eventually trickles down to the civilian world, and, in the case of the NGSW, it has already arrived. The .277 Fury cartridge has been introduced commercially in the SIG Cross bolt-action rifle. A limited-edition, semi-automatic-only version of the XM5, marketed as the MCX-Spear, has also been offered by SIG. In September, the company announced the MCX-Spear LT, a mid-size platform based on the XM5 offered in 5.56 NATO, .300 Blackout and 7.62×39 mm in rifle, short-barreled rifle and pistol configurations.

Innovations that did not win the NGSW competition have also made their way to the civilian world. This spring, SAAMI certified its first composite-case ammunition manufactured by True Velocity. Currently available in .308 Win., there are plans for the company to commercially release 6.5 mm Creedmoor and 5.56 NATO composite-case cartridges in the near future.

Looking Forward

The NGSW weapons are scheduled to complete their operational test by the third quarter of 2023, with the first Army units equipped with the new firearms in the fourth quarter of that same year. The entire roll-out to the “Close Combat Force” (a classification that includes infantrymen, cavalry scouts, combat engineers and forward observers, in addition to special forces) will be dependent on when ammunition production can be ramped up to meet demand. Like the M17 handgun recently adopted, other branches of the U.S. military, such as the Marine Corps, may end up adopting the XM5 and XM250 as well. The M4 and M249 will continue to soldier on with second-line support troops.

The NGSW program marks a radical departure in U.S. small arms doctrine, pushing the envelope of conventional cartridge performance and pairing it with a state-of-the-art optical system that can help soldiers make hits to the limits of their weapons’ potential. In an age of UAVs and precision-guided munitions, the individual combat soldier is expected to become a more precise instrument, and the NGSW program is providing the tools for the job.

It demonstrates that, on an increasingly sophisticated battlefield, the infantryman isn’t being replaced by technology, but adapting to meet new challenges, as no amount of innovation will change the fact that wars are ultimately won by boots on the ground and with rifles that soldiers hold in their hands.

The ultimate judgement about whether the path taken by the NGSW program is correct will come on the battlefield.

click here for enlargement

Conflicts in the early decades of the 21st century have highlighted deficiencies in U.S. small arms doctrine. To address these shortcomings, the military’s Next Generation Squad Weapons program settled on a new cartridge, rifle and machine gun. This table places current and future U.S. small arms in the larger context of firearms used by other nations.