Category: Soldiering

New Delhi, India

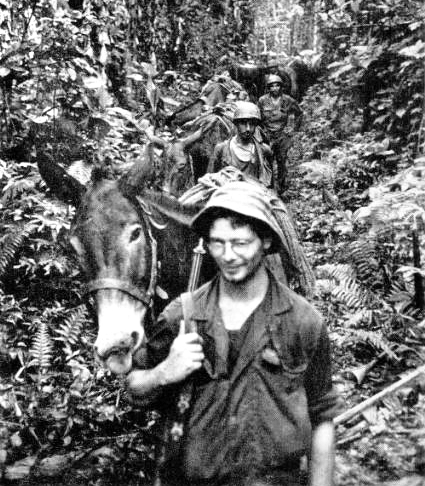

If army mules ever get to swapping barnyard yarns after this war, the mules of Merrill’s Marauders should outbray all the rest. For early this year those long-eared veterans of the Burma jungle slogged their way for four months straight over 700 miles of muddy trail and precipitous mountain tracks on the march to Myitkyina. Without those heavy-laden pack animals from Missouri, Texas and Tennessee, Merrill’s fighting foot soldiers might never have captured that strategic Japanese airfield for General Stilwell’s forces.

The Marauder mules were activated at Fort Bliss, Texas. After two months at sea they arrived in Calcutta, slightly underweight but none the worse for having weathered a heavy seven-day storm and two unsuccesful torpedo attacks.

The mules had scarcely got their land legs back when they were sent on the trek to Myitkyina. On that long jungle march each carried, in addition to 96 pounds of saddle, 200 pounds of essential equipment – light and heavy mortars, 75-mm pack artillery, heavy and light machine guns, ammunition, radio equipment, food, medical supplies.

Among the Marauders only about 150 were trained mule skinners. Thus, on the eve of the march to Myitkyina, each of several hundred former clerks, salesmen, factory workers and garage hands suddenly found himself in charge of one of Nature’s strangest four-footed creatures – the sterile, stubborn but almost lovable mule.

Many of the Marauders possessed as little animal lore as the British officer who, on receiving a consihment of sleek, fat-bellied mules, wrote that the mules looked all right, except that half the damn things were in foal. Once, at the end of a long day, General Merrill said to a disheveled, weary mule skinner who was laboriously rubbing down his mule, “You seem to take good care of your mule. Had much experience in the States?”

“Well, sir,” said the soldier, “I saw a mule once, in Brooklyn, hitched to an ice wagon.”

To train a man to be a mule skinner is no easy task. It is so difficult, in fact, that General Merrill said after Myitkyina had been reached, “Next time give me mule skinners and I’ll make doughboys out of them instead of trying to turn doughboys into mule skinners.”

Many of Merrill’s men, however, became passable mule skinners. They learned how to pack a mule so that his load was evenly balanced.

| IN THE BURMA JUNGLE, A MULE BECOMES U.S. FOOT SOLDIER’S BEST FRIEND |

And, camping at night, they always groomed, watered and fed their mules before finally bedding down near their charges.

The mules soon developed a fine instinct for jungle and mountain trails. But occasionally one would slip or fall exhausted from a precipitous path. Then the mule skinners would climb laboriously, often dangerously, down the mountainside and hack out steps by which the mule could climb up to regain the path.

Basic cavalry training had made them “bell-crazy,” for they had learned to drill by following a mare with a bell. It was, of course, necessary in the jungles for mules to disperse under attack and to act under the direction of each individual mule skinner. At first they insisted on following each other. If they were dispersed they balked and brayed. Later they showed excellent battle discipline, separating quickly and quietly.

At Walawbum, however, where a Marauder unit found itself greatly outnumbered by Japanese, the mules took it into their heads to bray lustily. Says General Merrill, “The Japanese were evidently fooled by the mules. They thought we had them greatly outnumbered and they didn’t dare attack, thanks to those mules.”

At Nphum Ga, where the Marauders were surrounded by a superior force for over two weeks, many mules were lost from starvation, thirst and artillery fire (a mule can’t get in a foxhole). The Japanese controlled the only water hole. Men were wounded trying to take animals to water. Eventually they had to send the mules to the water hole by themselves, unharnessed, since the Japanese could catch the harnessed mules. One mule was sent to the water hole at night to draw Japanese fire, so that Japanese positions could be located for a forthcoming attack. Later, when the action was succesful, the mule was found dead, with a huge steak cut away from one haunch. At Nphum Ga some of Merrill’s Marauders were killed while caring for and burying their mules.

Each mule skinner has his own mule whom he names Jake or Puss or Shorty but whom he usually calls “you ——” or “— — – —–.” These are terms of endearment for one’s own mule, but dangerous cursing when applied to another’s, Listening to this almost endless stream of profanity directed muleward, a novice is apt to inquire sympathetically, “What’s the matter with your mule?” The invariable answer is, “There’s not a damn thing the matter with it, it’s the best damn mule in the jungle.”

A mule always has a reason

Any good Marauder mule skinner defends mules vigorously against any of the usual charges made against them. A mule is not stubborn, he is practical. A mule doesn’t want to be disagreeable unless he has to. He just sensibly follows the line of least resistance. If he balks or kicks, he has a reason. Caught in a tight spot, a mule never kicks himself to death or flounders as a horse often does. He sensibly waits for help. A mule doesn’t fret and give way to nerves as men and horses do, he makes the beat of things. He is well-behaved under fire and bombing.

He never gets shell shock. He has much more endurance than a horse and, unlike the horse, he has too much sense to overeat and overdrink. A mule is in fact, say Merrill’s Marauders, a pretty savvy creature all round. As Colonel R.W. Mohri, the Burma mules’ vet, puts it, “A mule’s every bit as intelligent as a human being. Probably more so. So to get along with him you need to have, if possible, as much sense as the mule.”

A mule is as brave as he is intelligent, and the only thing that frightens him in the jungle is the elephant. The elephants fortunately are likewise terrified of mules. In encounters, both run away at top speed, filling the sir with their trumpeting and braying.

Marauder mules have proved themselves first-class “jungle wallahs.” After months of long, exhausting marches through mud, across rivers, up and down mountains, in thickest jungle growth, harassed by leeches and flies, shrapnel and bullets, most of them were put to work when they finally arrived at Myitkyina carrying supplies from the planes coming in to the airfield. Many are there now and eventually, instead of marching back out, they will be turned over to Chinese troops. Some days these mules from Missouri, Texas and Tennessee will undoubtedly find themselves marching to China over the Burma Road.

One out of all the numerous mule yarns has become a favorite with the Marauders, who are all volunteers. A mule skinner, exhausted by continual arguments with his mule, which consistently refused to climb mountains, cross rivers or otherwise overexert himself, finally lost his temper when the mule lay down and refused to budge. “Get up, you — — – —–,” snarled the driver. “You’re a volunteer for this mission, too.”

What would you do if you came into some serious money? I don’t mean you inherited a couple thousand bucks from crazy great-aunt Mildred. I mean what would you do if you were suddenly just filthy rich?

We’ve all pondered it. Last week some unidentified person in California won more than $2 billion in the Powerball lottery. Before that guy walked away with all that cash I admit that I entertained myself in quiet moments imagining what I’d do with such a windfall. I’d bless my friends and family, to be sure, but I’d also buy an island along with my own vintage Spitfire. Anyway, considering I have never bought a lottery ticket, the chances of my winning the lottery are pretty small. Of course, the odds wouldn’t change a whole lot had I actually bought a lottery ticket, either. That’s honestly the point.

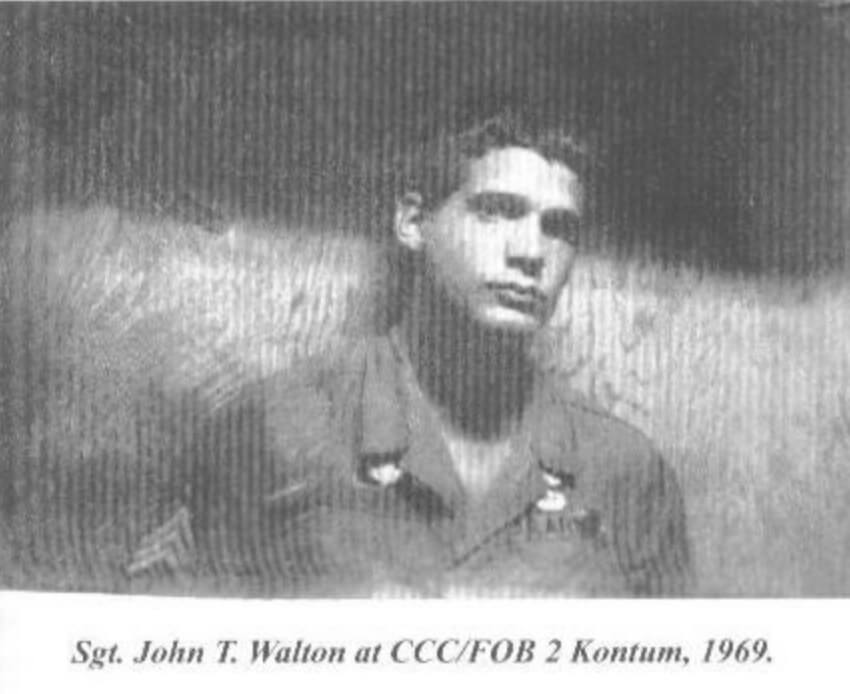

Some folks are born into money. Others work really hard or are just plain lucky. As the second son of a dime store owner from Arkansas named Sam, John Walton wore his wealth well. In great part, this is likely because young John had known some proper suffering before he got rich. Much of that hard experience he got while in uniform.

John Walton was the second of four kids born to Sam and Helen Walton. In High School, John was a dichotomy. He was a star football player who also enjoyed playing the flute. After graduating from Bentonville High School in Bentonville, Arkansas, he attended the College of Wooster in Wooster, Ohio. In 1968 he dropped out of school so he could better his skills as a flutist. After reading about the Tet Offensive, John Walton enlisted in the Army.

John Walton had good genes and a killer work ethic. In short order, he was a fully qualified Special Forces medic assigned to the Studies and Observations Group in Vietnam. He saw combat in the A Shau Valley as well as in Laos and Cambodia. During his cross-border forays, he was assigned to Spike Team Louisiana operating out of Forward Operating Base (FOB) 1 in Phu Bai. These stone-cold SF warriors would insert via helicopter to monitor movement along the Ho Chi Minh trail and call in air support to interdict enemy formations as the opportunities arose. Such stuff required simply legendary bravery and epic fieldcraft.

August 3, 1968, was a Saturday. SP4 Walton was deep in the suck in the A Shau Valley alongside five other members of his recon team. His unit was compromised and attacked by a numerically superior NVA force. In short order, the team was surrounded and immobilized. With the incoming fire now utterly overwhelming, the team leader called a Prairie Fire mission for any nearby strike assets. Prairie Fire meant that an SF team was about to get annihilated. Anything with a gun or a bomb was expected to answer the call.

The NVA knew that Americans had access to overwhelming firepower and that the key to success was to get in close and stay there. With automatic weapons fire and grenades raking their position, the spike team leader reluctantly called in an A-1 Skyraider to drop on their own position. The strike killed one member of the team, severely wounded the team leader, and blew the radio operator’s right leg off. To make things worse an NVA soldier got a clear line of sight and shot the fourth Green Beret four times with his AK-47 before being killed by John Walton, the only team member still intact.

John was an SF medic, and those guys could do some amazing medicine in the field. SP4 Walton assumed command of the team and went to work stabilizing the wounded while also manning the radio. Amidst everything else, SP4 Walton continued working the Tac Air, calling down fire on the tenacious NVA troops.

Three rescue helicopters answered the call. The first onsite was an antiquated H-34 Kingbee flown by a South Vietnamese pilot named CPT Thinh Dinh. The H-34 was, by the standards of the day, a piece of crap. Powered by a reciprocating radial engine rather than the jet turbines that drove American aircraft like the UH-1 Huey and OH-6 Loach, the H-34 was woefully underpowered, particularly in the thick hot environment of the A Shau. Despite suffocating ground fire, CPT Thinh bravely brought his aircraft into a nearby clearing and set it there as enemy rounds chewed through the airframe.

SP4 Walton dragged his teammates out to the aircraft one at a time until the antiquated helicopter was as heavy as it could be and still fly. Walton, for his part, would have to wait on the next bird. As soon as the young medic was clear CPT Thinh lifted off and nosed over toward the nearest field hospital. Then he heard over the radio that the next two rescue aircraft had turned away due to the overwhelming volume of ground fire. With that, CPT Thinh torqued his overloaded Kingbee around and headed back into hell.

Thinh landed his fat aircraft in the same spot and stayed there until Walton could get on board. However, now the old helo couldn’t hover. With enemy automatic weapons fire chewing the aircraft to pieces, the brave South Vietnamese pilot got the aircraft teetering up on its forward landing gear struts. In this awkward configuration, he pivoted the machine around until it faced a nearby draw. He then allowed the helicopter to roll downhill until he could take advantage of effective translational lift and actually break ground and clear the jungle. In this sordid state, CPT Thinh nursed his stricken aircraft to safety, saving Walton’s life in the process. Once the dust settled SP4 Walton was awarded the Silver Star for his courageous actions in saving his team from certain death.

In the aftermath of this particular mission, Walton confided to his friends that, if he lived to get home, he planned to buy a motorcycle and travel. Along the way, he hoped to learn to fly and explore Mexico, Central, and South America. For many to most folks, such stuff would never get past the dream phase. However, this was Sam Walton’s son. As we discussed before, he had good genes.

While John was in Vietnam, his father Sam had been busy. By the end of 1967, he had 24 Walmart stores operating in Arkansas. The following year he opened his first stores in Missouri and Oklahoma. By 1975 Walton had 125 stores and 7,500 associates with total sales of $340.3 million.

Soon after John got home he was flying for his father scouting out new locations for Walmart stores. In short order, he left Walmart to work six months out of each year as a crop duster. The rest of the time was spent in a VW bus exploring Mexico and places further afield.

Along the way, he co-founded Satloc, a crop-spraying company that pioneered the use of GPS in aerial chemical applications. He then moved to San Diego and founded Corsair Marine, a company that built trimaran sailboats. He also founded True North Venture Partners, a venture capital organization that used money to make even more money. By then he had accumulated some proper resources.

Despite his newfound wealth, John Walton apparently remained a really nice guy. He started a philanthropy called the Children’s Scholarship Fund that provided low-income kids with money to attend private schools. Like his dad, John still appreciated a modest lifestyle. While he and his wife Christy split their time between their trimaran sailboat and a historic beach house, he nonetheless drove an inexpensive and efficient Toyota hybrid car.

In 2003 his old Special Forces team held a reunion in Las Vegas in honor of the pilots who had supported them in Vietnam. By then CPT Thinh, the stone-cold South Vietnamese pilot who had saved his life in the A Shau Valley, had successfully relocated to Fargo, North Dakota.

He and Walton had remained close for thirty years after the war. However, Thinh lacked the resources to make it to the reunion. John Walton flew his jet up to Fargo, retrieved his old friend and his family, and took them to Vegas for the event.

By 2005 John Walton was worth $18.2 billion. He was the 4th-richest person in America and the 11th-richest person in the world. At 58 he had led a truly extraordinary life. He kept himself fit and healthy and enjoyed skiing, hiking, skydiving, flying, motorcycle riding, and scuba diving.

On June 27, 2005, at around 12:20 in the afternoon, John Walton lifted off from the Jackson Hole Airport in Wyoming in a CGS Hawk Arrow homebuilt ultralight airplane. Walton had performed a minor repair on the aircraft previously and improperly installed a rear locking collar on the elevator control torque tube. This allowed the torque tube to slide rearward after takeoff and produce slack in the elevator control cable. The cumulative result was a loss of pitch control. Walton was killed in the resulting crash.

Many folks die peacefully in their beds after a long life lived in obscure anonymity. Others may go out violently or at the mercy of some disease or other. John Walton lived life to the full. Warrior, medic, pilot, husband, father, and philanthropist—John Walton packed an awful lot of living into his 58 years.

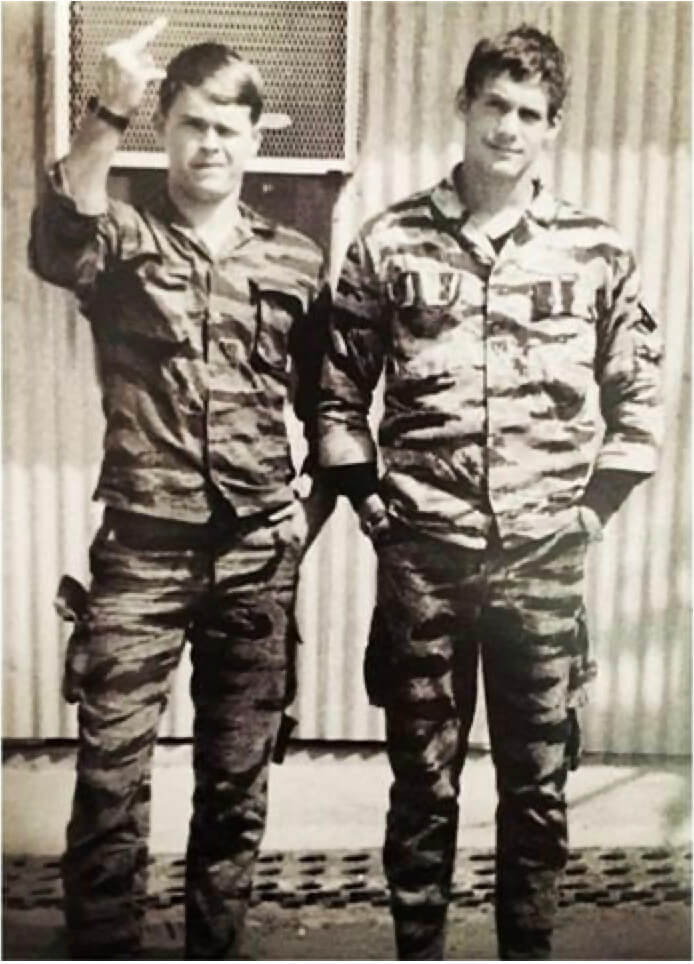

Addendum–I draw these projects from whatever I can find online. They are obviously only as accurate as the original source material. A teammate of John Walton’s named John Stryker Meyer reached out about some technical inaccuracies in this piece. Meyer is the character giving the finger to the photographer in one of the previous photos. After a delightful phone conversation I have made the changes. Based upon his personal descriptions, John Walton was clearly a truly extraordinary man.

Meyer authored a book on his experiences with MACV-SOG In Vietnam titled Across the Fence. It is available on Amazon. If the book is anything like he is it is likely a superb read. Thanks, brother.

CCR-Fortunate Son.

Just before Christmas, the US Marine Corps held their 248th Birthday Ball in a hotel in London. It was a lavish evening, with medals galore on display, dinner and dancing. But the highlight of the night’s revelry was a nine-minute video. Set to a soundtrack of Future Warrior by Audiomachine, it began with a thrilling montage: of ships steaming through choppy waters, planes doing death-defying loops, helicopters buzzing low over hostile territory and lots and lots of guns, fire and explosions. “Si Vis Pacem Para Bellum” flashed up on the screen. “If you desire peace, prepare for war.”

“Even I was on the edge of my seat,” says one British Army officer who was there. “I thought, ‘I want to join the US Marine Corps right now’.” That, he adds, “is the s— we need.”

In 2022, the US Marine Corps stood at 174,577 troops, with another 32,599 on reserve. In 2020, the Corps received 358,240 applications and accepted just 38,800 of them. Its annual budget is roughly $53.2 billion (£42.1 billion); US defence spending as a whole stands at $877 billion. It’s an unholy sum, and one that throws the state of the British Forces into stark comparison.

That British Army officer is one of just 75,983 regular full-time personnel in the country, with 28,284 reservists backing them up; the lowest numbers since the Napoleonic wars – although the Army nevertheless has the largest number of personnel of all three Armed Forces. Recruiters signed up just 5,560 regular soldiers last year – well below the target of 8,200 – and the outsourcing recruitment contractor, Capita, has admitted it will probably miss this year’s target of 9,813 by a third. Reports suggest that, at the current rate of striking, the British Army will field fewer than 70,000 soldiers within two years.

Britain might be the sixth largest spender on defence in the world (the figure currently stands at £45.9 billion), but a National Audit Office report into the Ministry of Defence’s (MoD) Equipment Plan found that the Army was £12 billion short of the funding required to meet the full demands of last year’s Integrated Review Refresh. The gaps are obvious, and sometimes embarrassing. The 155th Artillery Regiment currently has no guns – we gave them all to Ukraine, along with most of the ammunition needed to fire them. Our 240 or so Challenger tanks date largely to the 1980s and 1990s; the Army has an upgraded version on order, but will only have 18 of them by November 2027 and the full complement of 148 won’t arrive until the end of 2030. There’s not enough money for basic weaponry, let alone to produce a fancy video showing hordes of soldiers blowing stuff up with it.

Little wonder, perhaps, that earlier this week, senior US generals declared Britain to be no longer a top-level fighting force. And even more alarming that the current state of the world may demand us to up our game within fairly short order. So where’s it all gone wrong? And how can we fix it?

‘Start thinking soldier’

Ask your average soldier why he signed up, and a significant majority – if they’re honest – will say they’re in it for the drama, danger and excitement. Or, as one Army officer puts it bluntly, “they want a scrap, and to be able to bayonet someone in the face.”

In this century, the high point of British Army recruitment was 2003, when 16,690 people signed up to fight for Queen and country – just under the previous peak of 16,963 in 1999. At the time, there were plenty of opportunities to fight. In March that year, British troops joined the Americans in invading Iraq, overthrowing Saddam Hussein and occupying the country after a month of fighting that would grow into a conflict of six more years. At the same time, Britain’s Army was also deployed in Afghanistan following the 9/11 attacks. Young men and women signed up in their thousands: average Army recruitment throughout the 2000s was 14,459 per year.

The MoD spent heavily to recruit during those war-filled years: £20.5 million in 2002-03, £20.3 million in 2003-04 and a whopping £33.2 million in 2004-05. Reflecting the difficulties of attracting recruits to the infantry, in 2006 a special infantry recruitment campaign was run at a cost of £5.25 million. Soldiers were harvested from estates in the likes of Glasgow and Liverpool, where the Army offered them a way out of what could otherwise be a pretty tough life: 24 per cent of all Army applicants in 2003-04 were unemployed for a significant period before applying. There was adventure on offer, yes, but also the promise of engagement with an enemy force, and a clear moral divide between them and us. Like the recruitment posters of a century before, the harsh reality of war – the fight, but also the potential sacrifice – was not shied away from. As a recruitment poster from 1934 put it: “Members of the Armed Forces need to be capable of dealing with death and disaster on a daily basis.” The same was true once again. Plus, of course, the chance to bayonet someone in the face.

Fast forward to 2010, however, and things looked rather different. The war in Iraq was winding down. Troop numbers had reached their peak in Afghanistan, at around 10,000, but the nation was growing weary of this long, unwinnable war, especially as the number of fatalities had also peaked; over 100 personnel were killed between 2009 and 2010. Grappling with the aftermath of the global financial crisis, the coalition government was embarking on austerity measures, and in the 2010 defence review, under Liam Fox, the then defence secretary, it was announced that there would be a major cutting back. The Army would shrink from just over 100,000 soldiers to 82,000 by 2020, and would get smaller still by 2025.

“Start thinking soldier” proclaimed a 2010 recruitment video – still set in the desert of Afghanistan but notable for an absence of tanks, helicopters or additional manpower. “Would you mortar them, bug out or engage?” was the question asked of the potential recruit. It’s difficult not to wonder whether the MoD might have been asking itself the same questions. “That was in theory when they [the government] wanted to prioritise equipment, but doing that within the defence budget meant having to make savings somewhere else,” recalls Gen Lord Richard Dannatt, who handed over as head of the Army in 2009. Those savings, he points out, therefore had to be in manpower, “and most of the manpower is in the Army”. By 2012, Army numbers had fallen to under 100,000 and retention was also dropping, with the numbers leaving jumping from 11,500 in 2011 to 13,200 in 2012.

That was also the year that the Army signed a 10-year recruitment contract with the outsourcing giant Capita. Prior to this, recruitment had been carried out by specific teams within military units. Walk into a recruiting office anywhere across the country and you could have had a face-to-face conversation with a soldier, sailor or airman, and be starting basic training within weeks. But with the axe of redundancy swinging, the MoD needed soldiers back in their day jobs.

The Army said the deal with Capita would release over 1,000 soldiers back to the front line, and deliver hundreds of millions of pounds in benefits to the Forces. But the new arrangement was beset with problems from the outset, from technical difficulties with the new online recruitment system to interminable waits after signing up. Auditors found that, in the first six months of 2018-19, it took up to 321 days for new recruits to get from starting an application to beginning basic training; in 2017-18, nearly half – 47 per cent – of applicants dropped out voluntarily, with the delays believed to be a significant factor. The Army estimates there were 13,000 fewer applications between November 2017 and March 2018 than in the same period the preceding year.

The hope at the time was that the Army Reserve would grow to make up the shortfall. But there were manifest problems with this approach: first, a lack of a clearly defined purpose for reservist troops, second, a pay rate that for many didn’t seem worth it for the disruption to their everyday lives and, finally, the same lack of investment in recruitment that beset the regular Army. A 2013 White Paper under Philip Hammond, who by then had taken over from Liam Fox as the defence secretary, proposed military pensions and healthcare benefits for reservists, as well as increased pay, in a £1.8 billion bid to drive up numbers from 20,000 to 30,000 by 2018, at which point the reserves also saw a name change from the Territorial Army to the Army Reserves. But at the same time, some 26 reservist bases of a total of 334 closed down. As former regular and reservist soldier John O’Brien wrote to The Telegraph recently, “these centres served as a vital gateway, introducing young people to military life. The effort of travel within a rural county puts possible recruits off.”

Things haven’t improved much since. The number of reserve bases is now down to less than 50, and, while reservist numbers have increased marginally since 2012, at around 1.2 per cent – despite the MoD signing a further two-year recruiting contract with Capita last June, there was a 35 per cent decrease in people joining the Reserves between 2021 and 2022. The following year, 5,580 reservists left and only 3,780 joined. Part of the problem is mindset, says one frustrated Army officer who works regularly with reservists. Fundamentally, he says, “they’re civilians. They have no idea how to behave like ordinary soldiers, and have none of the credibility.” What’s more, with no requirement to actually deploy, their efficacy is perhaps questionable, especially when it takes time to train reservists up to standard. “You can’t train a reservist to use a tank overnight”, points out one officer who has done several stints on the recruitment front.

Aside from the antiquated process, part of the problem in its recruiting of both regular and reservist forces, says the officer, is that Capita “measures success as people who come through the door, instead of the people who complete the training”. To succeed in getting the right men and women into a position to fight, he says, the system needs “to move from assessments to tests. A test is something you pass or fail. An assessment means someone only needs to attempt it. But to close and kill the enemy, you need to deliver to the standard required, and the standard is a test, not an assessment.”

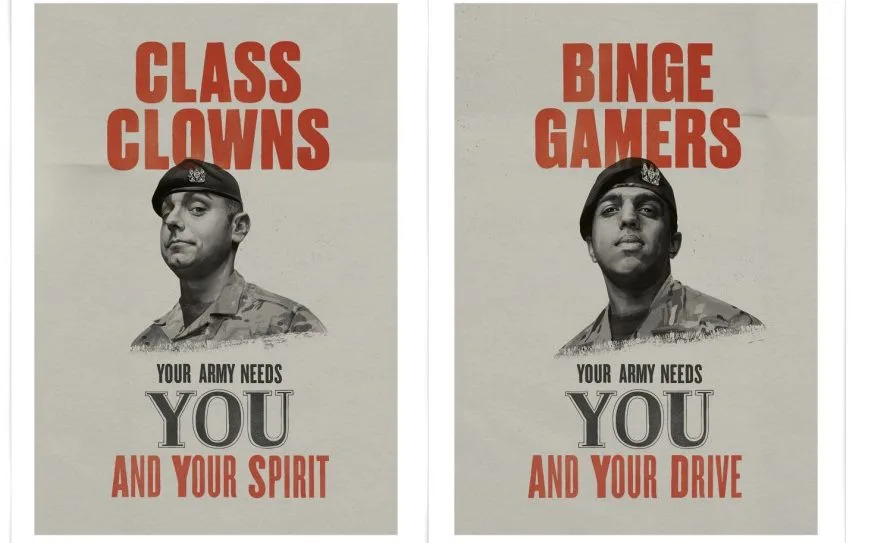

There’s also the issue of who’s being targeted in the first place. In recent years, recruitment campaigns have, in the view of many, “gone soft”. In 2016, military chiefs sought to appeal to a supposedly altruistic Gen Z with reverse psychology. “Don’t join the Army,” its campaign declared; “don’t become a better you.” This was followed by 2017’s “This is Belonging” campaign, telling the stories of soldiers who believed they wouldn’t fit in to demonstrate that all are welcome. In 2019, the “Snowflakes” campaign called on “snowflakes, selfie addicts, class clowns, phone zombies and me, me, me millennials” to join its ranks in a campaign that infuriated not only an older generation but many serving personnel too. In September of last year, it was “You Belong Here”, “to challenge the misconceptions among the 59 per cent of young people who do not believe they would fit in.”

“There’s so much wokery and mixed messaging,” says one former Marines officer. And, while these campaigns may have been successful in attracting those who might not otherwise have thought of a career in the military, the problem is that they have ignored what has always been the Army’s traditional recruiting base: white, working-class boys (and girls) between 16 and 24 who want, as one Army officer puts it, “drama, danger, excitement, reasonable pay and a fight”.

These campaigns, he says, “don’t show tanks or anything blowing up. But my bit of the Army is there to fight and kill the enemy – and we’re not very good at telling people that’s our job.”

‘Armies are not easy to create’

So what now? Europe is teetering on the brink of all-out war. If it breaks out, Britain would have to step up to fulfil its Nato commitment. So do we really need the citizen armies that Gen Sir Patrick Sanders alluded to last week? And what about the kit they would have to fight with?

“If the Government wants to make the Army as effective as it could be, it requires total governmental and political support, sustained investment, and a sense of urgency to do things quickly,” says former brigadier Ben Barry, a land warfare expert at the International Institute for Strategic Studies. He outlines three main priorities: accelerating recruiting, a return to fully collective, large-scale training and a renewed focus on the logistics of weapons procurement. People, says Barry, are key – and, he says, “to be brutally frank, if you want sustained readiness, the high priority has to be the regular Army” – not the Reserves. (It’s sobering to remember that in the first six months of fighting in Ukraine, the Russians took the same number of casualties as the headcount of the entire British Army.) That means improving the offer to attract and keep the good people, from implementing pay review recommendations, to retention bonuses for those serving, to a massive improvement in the standard of living accommodation. “We have to make a better offer to those who might be wanting to join,” agrees Lord Dannatt – and get front-line soldiers back into recruiting offices to attract the brightest and best.

That’s not to say there isn’t a role for reservists, who might also be bolstered by a larger, better and more engaged regular force. Should we introduce some form of national service – that citizen army that Gen Sanders referred to – in the manner of our European counterparts in Sweden, Finland and Norway? Difficult, when military life has become so segregated from its civilian counterpart. As Richard Munday wrote to The Telegraph recently, even “organisations like the National Rifle Association, and events like the King’s Prize at Bisley, are ghosts of their former selves because their objectives have been countered by political decisions that have sought to segregate the military from civilian life, and sporting skill and interest. If we are serious about the need to maintain a credible Armed Forces in the future, we must bridge that divide.”

“Armies are not easy to create”, points out Maj Gen Chip Chapman, a former paratrooper and senior British military adviser. “You need motivated people who will join because they see it as vital for the UK’s interest. The worst thing you could have is people being coerced to join.” Instead, says the Army officer with recruitment experience, “more effort needs to be made to get people who have previously served back in [as reservists] – because it’s experience we’re lacking now.” Another suggestion is for all fit and willing former regular soldiers, numbering some 200,000, to be invited to take part in annual military exercises.

Next is kit, which Britain is woefully lacking: we’re low on guns, we’re low on the ammunition to shoot them, we’re low on tanks and the two aircraft carriers on which the majority of the defence equipment budget was blown in recent years are undeployable as Britain doesn’t have enough sailors to man them. We’re also majorly lacking in layered air defence – the ability to fight off attacks at both short, mid and long range. Recent suggestions that the carrier HMS Elizabeth could be deployed to fight off Houthi attacks in the Red Sea ignores the fact that we are lacking the jets to put on them that would provide the long-range cover.

“The situation could be better,” admits Nick Reynolds, research fellow for land warfare at the Royal United Services Institute. Part of the problem, he says, is that modernisation across the board was delayed by the Helmand campaign, which means everything needed to be brought up to date at once. But, he says, the Ukraine war has highlighted some stark requirements: first, the need to produce and stockpile munitions quickly and on a mass scale; second, to simplify the bureaucratic procurement system, cutting out the cronyism, and third; invest in air defence capability across all ranges. “Unfortunately, we’re now in a position where having sovereign capability and a large workforce with a significant amount of expertise is a very valuable thing – but we allowed that to atrophy,” he says. “We need a more sustainable arms industry, to produce things in-house.”

It would, he says, involve a massive expansion of the UK domestic arms industry – a prospect many might feel uncomfortable at. But doing so could also bring job creation and boost the economy. The question, says Reynolds, is whether – as a country – we are willing to have that conversation with ourselves.

Of course, all of this doesn’t come cheap. The Army has a £44 billion procurement plan over the next 10 years, but, as Gen Sanders has pointed out, just 18 per cent of that money is committed – a dangerous position to be in during an election year. And, says Lord Dannatt, we should mind the lessons of history. In 1935, for example, Britain was spending less than 5 per cent of GDP on defence. When war broke out that figure shot up to 18 per cent, and when the country was fighting for survival in 1940, it went up to 46 per cent. “18 to 46 per cent is the price you pay for disaster,” Lord Dannatt warns. “We have to be prepared to pay the price for deterrents. Even going up to 3 or 4 per cent of GDP would buy us sufficient Armed Forces to be credible within Nato.” Russia is right now spending nearly 40 per cent of its GDP on defence.

The MoD is aware of the problems. Last June saw the publication of the Haythornthwaite Review into Armed Forces incentivisation. Its brutal conclusion was that the current system doesn’t really work for anyone; it proposed a radical overhaul to resolve the tensions between career progression, operational effectiveness and family life. “Future recruitment is a top priority,” said an MoD spokesman, adding that the measurements the Haythornthwaite Review set out, from zig-zag careers where people can leave and re-join the Armed Forces, through to reviews of pay and progression, are being trialled and piloted. In December, meanwhile, more than 400 soldiers were ordered back into recruiting offices in a bid to get more people to enlist. And, said Grant Shapps, the Defence Secretary, in an interview with The Telegraph on Thursday, Army recruitment almost doubled last month alone amid growing fears of a confrontation with Moscow.

But as Britain looks to the future, the official British Army motto might be a salutary reminder. “Be the best”, it proclaims. To do that, it needs commitment, cash and political will. So, what will the recruiting video of 2024 show?