The year was 1987. A group of middle-aged men sat under the umbrellas at the cheap fiberglass tables of the Holiday Inn in Columbus, Georgia not far from Fort Benning. They deserved a Ritz-Carlton, but this would have to do. The sign out in front of the hotel, the letters hanging somewhat askew, read:

WELCOME 8TH AIRBORNE RANGER COMPANY

The comment about taking an unfortunate enemy round in the gluteus maximus was an affectionate jab from one member of the company to another, and it was met with howls of protest and laughter.

“Son,” a grizzled old veteran said gripping my shoulder while the other men tried to interrupt him. “Hush! Hush!” he said to them in mock annoyance before turning back to me. “I mean it went in one cheek and came out of the other just as neatly as could be! No bone, just flesh!”

The index finger of his right hand poked one of his own cheeks while the thumb of his left hand moved up and out on the other side, indicating the bullet’s exit.

The conversation turned to a man with an even more unfortunate war wound.

“I tell ya, he thought his life with the ladies was over.” The other men listened expectantly for the ending of a story they knew well. “There was so much blood, we feared he had been gut shot! But, nooo!”

“No!” bellowed another, like a member of the choir in a good Pentecostal church.

The teller of the story continued: “So, I pull his pants down and guess what? It was just nicked!”

Again, howls of laughter.

My father finished the story: “We just told him he’d have a good story to tell when it came to explaining how he got that scar.”

Men wiped their eyes and guffawed.

This was a reunion of the 8th Airborne Ranger Company, or what remained of it. The end of the American spear in Korea 1950-51, they were the handpicked elite from all airborne and subsequent Ranger units. Not surprisingly, 8th Company had the highest qualification scores in the history of the Ranger Training Command (RTC).

Over the course of that weekend, the Ranger School at Fort Benning would honor them with a demonstration of modern Ranger skills and tactics. The latest generation of Rangers would rappel from helicopters, make a practice jump, and tour them around Benning, the place where 8th Company was born in 1950. And, not coincidentally, it was where I was born.

The men of 8th Company were much older now and not as lean as the men — boys, really — who appeared in the photos from 1950-51. Most carried extra weight around the middle, had the leathery skin that came with years of overexposure to the sun, and old tattoos that had purpled with age on biceps and calves that were not as hard and chiseled as they once were — but you didn’t try to tell them that. Like old athletes, they spoke with as much bravado as ever.

I had to smile. It had been my privilege to be raised in the company of such men. They could be profane and the jokes were always off-color. They were, to a man, hard-drinking and chain-smoking. They incessantly complained about the army and were fiercely proud of their part in it. Ornery and ready to fight each other, they were nonetheless ready to die for each other, too. Their vices were ever near the surface and yet, I cannot imagine where America would be without their kind.

I was 20 years old and sat silently watching and listening as I so often did when my father swapped war stories with other veterans. But this time it was different. These weren’t just any veterans; these were the men with whom he had shed blood. This would be his last reunion and it was important to him that I be there. As the son of an 8th Company Ranger, I was, like other sons, an honorary member of this very exclusive club and therefore allowed to participate on the periphery of their banter — and fetch them beer. Lots of beer. Ranger reunions were impossible without beer. And with middle-aged men, that meant frequent trips to the bathroom.

With my father away for a moment on just that sort of mission, one of his old buddies leaned in as if to tell me a secret:

“If any man was ever born to be a soldier, it was your father. Some men have an instinct for the battlefield, and he damn sure did. Absolutely the best shot I ever saw. Could hit flies at a hundred yards. And, man, he was fearless…”

My father, returning, rolled his eyes: “That’s bulls–t, Mike. I was as afraid as any man.”

He turned to me. “It’s as I’ve told you before, son, a man who is truly fearless will get you killed. There’s something wrong with him. His instincts don’t tell him to be afraid when he should be. You want a man on point who wants to stay alive just like you do and whose senses are telling him ‘something’s not right here’ when there’s reason to believe you’re walking into an ambush. Now Mike here, was a helluva point man…” This was all very typical. They extolled each other’s battlefield heroics, but not their own.

Graduates of the 1950 RTC should not be confused with the more than 10,000 military personnel who wear Ranger tabs today and who do not serve in Ranger units. This is no slight to those who wear them. But as any Ranger will tell you, there is a difference between passing the Ranger course and serving as a Ranger, especially today where the standards have been watered down for political reasons. These men were truly elite as indicated by the high washout rate and the fact that of the 500,000 soldiers of the United Nations serving in the Korean War, there were never more than 700 Rangers.

Just as my father indicated, I had heard stories like this before, this old battlefield wisdom. My whole life, in fact. More stories followed. More laughter, backslapping, and beer. Indeed, the cans in the center of the table began to pile up and lips became looser.

Those of us who have heard a lot of old war stories, the wives, the sons and daughters, learn to distinguish the authentic from the fictional. Because the men who did the real fighting as these men had — and I mean the really brutal, prolonged, on the ground stuff where the sight and smell of the dead forever sears memories — they don’t like to talk about the details. Not even with each other. The guy who talks casually about what he did in combat? You can bet that he’s either a fraud or that battle has unhinged him.

“When your dad came home from Korea,” my Uncle recently told me, “he had a chest full of ribbons. He was a hero. But he wouldn’t talk about it in anything but general terms.” And nor did the rest of 8th Company who had their share of ribbons, too. The stories they told on this reunion weekend were mostly amusing, but to the veteran listener of veterans’ stories, you knew that the humor masked a horror.

All of these men dealt with the psychological wounds of war whether they ever received a Purple Heart or not. My mother tells me that my father suffered from hideous nightmares to the day he died, a recurring one being that he had fallen into a thinly covered mass grave full of bodies in a state of decomposition. Though he fights to climb out over the bodies, the rotten flesh slides off the bones as he grips them and their flesh remained on him for days until he could bathe, a luxury not afforded to men behind enemy lines. Though he would never say, she thinks the nightmare reflected an actual occurrence. I wager all of these men had nightmares of war.

Years later, as he lay on his deathbed delirious from the heavy doses of morphine, he returned to the battlefield. I will never forget his words, a command shouted with urgency and authority: “Cover the left flank! Cover the left flank! Move! Move! Move!” The order was repeated along with something about laying down suppression fire. Whatever the battle he was in, he was reliving it and he was determined to hold the line. In that moment, I prayed that the Lord would take him. He was suffering the horror of war all over again.

The next afternoon, his chest, heaving and belabored for days, relaxed and the air left his lungs in one long sigh. My father was dead.

A few days later, I sat solemnly with my mother going through his things. It was a joyless task. Buried among his memorabilia we found a letter from a fellow member of 8th Ranger Company, Thomas Nicholson. It was an award of sorts, but deadly earnest, and, again, the humor here serves a purpose — it makes a terrifying memory more tolerable to recollect. It read:

During combat operations in the Republic of South Korea, Charles Taunton bravely, but unknowingly, earned life membership in The Noble & Ancient Order of the Combat Boot…. He deserves the acclaim and friendship of all who learn that he unselfishly, and with little regard for his own safety, went behind enemy lines to assist a fellow soldier. This act of courage, which epitomizes the U.S. Army tradition of ‘never leaving an injured or deceased soldier in enemy territory,’ is worthy of great praise. Be it therefore known that I, Thomas Nicholson, was the injured soldier he carried back to friendly lines, and that it is with everlasting gratitude that I certify the truth of this citation.

Napoleon said that “Men will fight long and hard for a bit of colored ribbon.” Some men perhaps. But I never got the impression that the men of 8th Company cared about such things. They valued, above all, the opinions of the other men in 8th Company. To have the respect of the man who fought to your right and to your left, well, that meant something. In an interview with NBC News many years later, radio operator E.C. Rivera spoke with great emotion about his fellow Rangers and other Korean War veterans: “Nobody gave a rat’s ass about us. Nobody cared. They [i.e., people in America] were very cold to us.”

On July 27, 2013, the surviving members of the 8th Airborne Ranger Company gathered at the Army Heritage and Education Center in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. Led once again by their former captain, James Herbert, who was now a retired Brigadier General, the half dozen men sat with their wives and families. Before them stood Son Se-joo, the Consul General for the Republic of Korea, who had come to honor them:

In the face of overwhelming danger, your stories of valor and sacrifice saved our country and made it what it is today. As we pay tribute to you, I can confirm that the Korean War is not a ‘Forgotten War’ and that the victory is not a forgotten victory. The Korean people will never forget your sacrifice.

It was an honor long overdue, but too late for most. Coming as it did sixty years after the end of the war, most of the men of 8th Company were, by now, dead. Many had died on hills with no names, only numbers, in a country that was not their own, but in defense of principles they held dear. Others died later from wounds received in battle. And still more passed away as old men who fought in a war no one seemed to care about. Historian Thomas H. Taylor writes of 8th Ranger Company:

[Their] only tribute has been from their own post-war lives. Their collective lack of bitterness. Their forbearance from bitching about the lack of deserved recognition. This may be because they were mobilized but their nation was not. They went to war while their countrymen remained at peace. They fought, they bled, they won. Then they returned. Having given their all, they asked for nothing — and that’s just what they got.

I would add to this that satisfaction for the men of 8th Airborne Ranger Company came from something much more important to them than ribbons or recognition. It is something that only those who have known the battlefield can fully appreciate, but that the rest of us can glimpse in the terrible and inspiring story behind Thomas Nicholson’s humorous letter.

According to the Ranger Hall of Fame at Fort Benning:

On the 22nd of April 1951, 350,000 CCF [Chinese Communist Forces] troops launched their largest offensive of the Korean War. The attack broke the 6th Republic of [South] Korea Division that retreated 21 miles, leaving the right flank of the U.S. 24th Infantry Division exposed. The Commanding General of the 24th Infantry Division sent the 90 men of the 8th Ranger Infantry Company into this void.

It was in that void, on Hill 628, a godforsaken, bleak mass, that Thomas Nicholson was shot up badly. Wounded and expecting to die as the battle raged around him, he sat propped against a tree, bleeding to death and holding a hand grenade. His plan was to pull the pin when the enemy that surrounded them drew near, thus killing himself and as many of the CCF as possible.

But that’s not what happened.

Instead, his fellow Rangers came for him just as they came for every other wounded or dead American on that hill. Calculating that the CCF who surrounded them would not expect them to abandon their fixed positions on 628 and attack, the Rangers closed ranks, formed a spearhead, put the wounded in the middle, and assaulted the side of the hill between them and a company of tanks in the valley below (see no. 2 on this list of most heroic acts of bravery). One platoon remained on the hill to provide cover fire as the other two platoons slammed into the unsuspecting Chinese. The effect was devastating. Writes Taylor: “As the Rangers approached, Chinese came out of their holes in a banzai attack. They were mowed down — nothing was going to stop 8th Company unless every man took a bullet.”

They carried him off of Hill 628 just as a U.S. Navy gull wing Corsair fighter bomber descended, banked, and hit the mountain with napalm. Ranger Robert Black recalled it years later: “A black canister fell from beneath the plane and a moment later a towering gout of flame erupted from behind the hill.” For over a mile the Rangers fought their way through CCF lines until they reached the tanks where their wounded could be evacuated.

Thomas Nicholson spent the next 18 months in hospitals. He never rejoined 8th Company, but he did live to become a husband and father. He also became a helicopter pilot in Vietnam. Thirty years after the war was over, he issued “citations” to the men responsible for his rescue. My guess is that this included every man who fought to get all of the dead and wounded — a third of 8th Company — off of Hill 628.

When my father spoke with pride of his war record, it was never with a medal in mind. It was not in the recollection of some heroic act or a promotion. And it wasn’t in the body count of enemy dead, a statistic of which he never spoke. If I may borrow a phrase from E.C. Rivera, my father “didn’t give a rat’s ass” about any of that. No, he took great pride in one simple fact: in the history of 8th Ranger Company, they never left a man behind be he wounded or dead. Never. And if I had to bet, I would wager that the rest of the men in this remarkable company felt the same way.

Perhaps that explains why his mind went back to a specific moment in battle as death, the enemy he could not escape, closed in on him. Even in dying, the men of the 8th Airborne Ranger Company maneuvered to protect:

“Cover the left flank! Cover the left flank! Move! Move! Move!”

Larry Alex Taunton is an author, cultural commentator, and freelance columnist contributing to The American Spectator, USA Today, Fox News, First Things, the Atlantic, and CNN. You can subscribe to his blog at larryalextaunton.com.

1. Forget about knives, bats, and fists. Bring a gun. Preferably, bring at least two guns. Bring all of your friends who have guns. Bring four times the ammunition you think you could ever need.

1. Forget about knives, bats, and fists. Bring a gun. Preferably, bring at least two guns. Bring all of your friends who have guns. Bring four times the ammunition you think you could ever need.

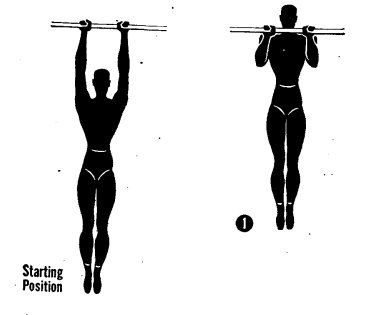

Movement. Pull up until the chin is above the level of the bar. Then lower the body until elbows are completely straight. Continue for as many repetitions as possible.

Movement. Pull up until the chin is above the level of the bar. Then lower the body until elbows are completely straight. Continue for as many repetitions as possible. Instructions. The men should be told that the most common errors are: getting the feet too far apart, forward and backward, and failing to squat down on the rear heel. The correct position should be demonstrated clearly, and the men should be given sufficient practice to master it. The action must be continuous throughout. Before beginning the event, the men should be told that it requires courage almost to the same extent as it requires strength and endurance and that they should not give up until they cannot make another movement.

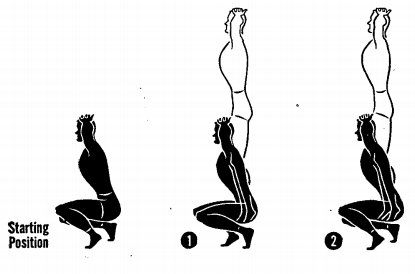

Instructions. The men should be told that the most common errors are: getting the feet too far apart, forward and backward, and failing to squat down on the rear heel. The correct position should be demonstrated clearly, and the men should be given sufficient practice to master it. The action must be continuous throughout. Before beginning the event, the men should be told that it requires courage almost to the same extent as it requires strength and endurance and that they should not give up until they cannot make another movement. Instructions. The performer is told: that the arms must be straight at the start and completion of the movement; that the chest must touch the judge’s hand; and that the stomach, thighs, or legs must not touch the floor. Hands and feet must not move from their positions. He is also told that the whole body must be kept straight as he pushes the shoulders upward; that is, the shoulders should not be raised first, and then the hips or vice versa. The judge uses his free hand to guide the man in case he is raising his hips too much or raising his shoulders first. In the first instance, he taps the man on the top of the hips to straighten them out; in the second case he taps underneath the abdomen to make him raise his abdomen with the same speed as his shoulders.

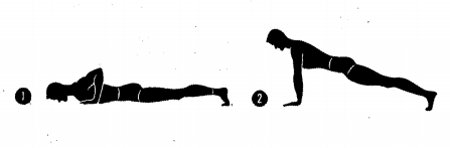

Instructions. The performer is told: that the arms must be straight at the start and completion of the movement; that the chest must touch the judge’s hand; and that the stomach, thighs, or legs must not touch the floor. Hands and feet must not move from their positions. He is also told that the whole body must be kept straight as he pushes the shoulders upward; that is, the shoulders should not be raised first, and then the hips or vice versa. The judge uses his free hand to guide the man in case he is raising his hips too much or raising his shoulders first. In the first instance, he taps the man on the top of the hips to straighten them out; in the second case he taps underneath the abdomen to make him raise his abdomen with the same speed as his shoulders.

Instructions. The performer should be warned that he must keep his knees straight until he starts to sit up; that he must touch his knee with the opposite elbow; and that he may not push up from the ground with his elbow.

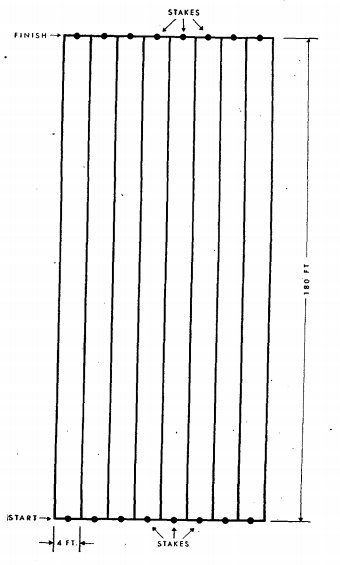

Instructions. The performer should be warned that he must keep his knees straight until he starts to sit up; that he must touch his knee with the opposite elbow; and that he may not push up from the ground with his elbow. Instructions. The men should be told to run about 9/10ths full speed, to run straight down the lane, to turn around the far stake from right to left without touching it, and to return running around the stakes one after another until they have traveled five full lengths. The men should also be instructed to walk around slowly for 3 or 4 minutes after completing the run. Recovery will be much more rapid if they walk than if they lie down.

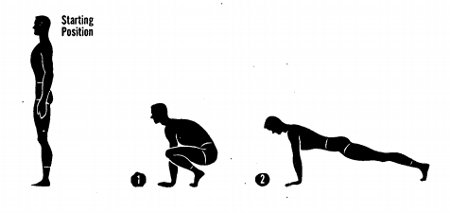

Instructions. The men should be told to run about 9/10ths full speed, to run straight down the lane, to turn around the far stake from right to left without touching it, and to return running around the stakes one after another until they have traveled five full lengths. The men should also be instructed to walk around slowly for 3 or 4 minutes after completing the run. Recovery will be much more rapid if they walk than if they lie down. Instructions. The men should be told that in executing this movement for speed the shoulders should be well ahead of the hands when the legs are thrust backwards. Extending the legs too far backward, so that the shoulders are behind the hands, makes it difficult to return to the original position with speed. On the preliminary practice, the performer is told he will score better if he does not make a full knee-bend, but bends his knees only to about a right angle; and that he should keep his arms straight. It is not a failure if he bends his arms but the performer will not be able to score as well.

Instructions. The men should be told that in executing this movement for speed the shoulders should be well ahead of the hands when the legs are thrust backwards. Extending the legs too far backward, so that the shoulders are behind the hands, makes it difficult to return to the original position with speed. On the preliminary practice, the performer is told he will score better if he does not make a full knee-bend, but bends his knees only to about a right angle; and that he should keep his arms straight. It is not a failure if he bends his arms but the performer will not be able to score as well.