Category: Ammo

The F-35 stealth jet isn’t the only example of expensive technology that crashed recently. The implementation of New York’s ammunition background check law – the rollout of which was, to be generous, extremely low visibility – was a disaster of its own, judging from initial reports.

The new law was actually passed as part of broader gun control legislation a decade ago. The so-called SAFE Act (2013) authorized a statewide ammunition background check database and required that the superintendent of the state police make a formal “certification” that the database was “operational” before the law could take effect.

Confusion over whether this has occurred and what the new changes involve is understandable. Readers of the government’s official “Gun Safety in NYS” website were still being given the following outdated information as of September 21:

Is there any background check now required for purchasers of ammunition?

Not yet. The law provides that background check requirements imposed on all retail sellers of ammunition are scheduled to take effect on September 13, 2023.

To complicate things, the implementation of the ammunition background check law coincides with another gun control development in the Empire State, pursuant to which the New York State Police (rather than the FBI) is responsible for conducting all firearm and ammunition-related checks using both NICS and a “statewide license and record database.”

The database requires detailed personal information about the purchaser: name, “up to five additional names/aliases,” residential address, date of birth, height, weight, race, ethnicity, “prior military status,” country and place of birth, citizenship, whether and what driver’s license or government-issued identification the person has, social security number, contact information, and (for ammunition buys) the manufacturer, the “Ammunition Identification Number,” the caliber and amount of ammunition being purchased. (The State Police guide for dealers has, out of a total of 21 pages, devoted eight to the initial personal information needed.)

All background check transactions currently “need to be processed online,” as an “Interactive Voice Response (IVR) telephone solution is in the process of being implemented but will not be available until October.”

Shortly before September 13, a gun store owner indicated that there was no outreach: “No dealer in New York has been contacted by the state about how it will work.” Other ammunition retailers complain that the new system isn’t actually working – apart from the time it takes just to enter the required customer information online, there are significant delays in getting the system up and running and in response times. “It took eight hours between a computer tech and me to play with their website to get their website working,” reported one gun store owner. Only a few days after the system went live, another retailer expressed frustration with delays before a sale could proceed, describing his longest wait time for a response (at that point) as 22 hours.

Even worse, an improper denial means the person has to appeal to the State Police and wait out the appeal period of up to 30 days before being able to purchase ammunition. Tom King, the executive director of the New York Rifle & Pistol Association and the holder of a state pistol permit for over 40 years, was denied when he tried to buy shotgun shells, and has since appealed. “They’re denying everybody I’ve talked to,” he said.

Gun owners are dinged with additional fees to pay for this, being $2.50 for ammunition purchase background checks and $9.00 for firearms, and the law will have other, less obvious financial repercussions. “We lose money on every box of ammo we sell because of the time involved,” one retailer says, adding that, “It’s not going to get easier. We’re going to have to raise our prices.”

A newsletter from New York’s Assembly Minority Office of Public Affairs confirms there are “very legitimate concerns about the burden this new system will place” on the business community, the State Police, and gun owners. “Costs will go up and it is unclear what benefits this new law will generate…This law targets law-abiding gun owners and puts yet another financial burden on already overtaxed businesses and individuals. It is hard not to look at this as anything more than a punitive fee for access to the Second Amendment.”

Empire State residents who are not gun owners won’t escape the reach of this folly, either – a reported $20 million in the 2023-24 budget has been allocated for the State Police for implementation, including the hiring of 100 additional personnel.

The most ridiculous thing about all this wasted time, money, ink and effort is that New York’s dangerous criminals will continue to flout the law. The executive director of one New York gun control group was quoted as saying that, although “lawful gun owners may have to wait a bit longer right now in the immediate, they themselves understand what could potentially happen if an individual who does not have a license or does not pass a background check is able to obtain that gun.” Contrary to her claims, lawful gun owners understand all too well that criminals don’t waste time jumping through government hoops to buy guns or ammunition. “The only people that this is affecting,” says Tom King, “is the lawful legal citizen in New York state.”

————————————————————————————– I am sure that up state New York is just over joyed by this. Thanks to NYC and its choices that they make. Grumpy

Sometimes I wonder whether folks working at a gun manufacturer know the impact of their decisions beforehand. I spent a little time at a couple of gun manufacturers many years ago. A couple of guys clearly dreampt of being the next John Moses Browning but most just liked the idea of working where guns were being made.

So as the 20th century was about to debut, the brass at Smith & Wesson decided on a new double-action revolver design called the Hand Ejector Model. More powerful cartridges were in high demand so the company developed a solid frame with a swing-out cylinder to replace its top-break double actions. The first of these were the I- and K-frame Hand Ejectors in .32 and .38 cal. These revolvers were an instant success as the 19th century drew to a close, so a .44-cal. frame given the factory name of the N-frame was developed in 1905. The .44 Russian cartridge was designed for and during the Top-Break era. This new N-frame allowed for a more powerful cartridge so the engineers lengthened the .44 Russian case by .19″, added 3 grains of black powder for a total of 26 grains to push a 246-gr. bullet to 750 f.p.s. The new cartridge was christened the .44 Smith & Wesson Special, tagging along with the already popular .38 Smith & Wesson Special.

These new .44 Hand Ejectors were made to very tight tolerances. Cylinder alignment was critical and these cylinders locked up in three places; the front of the extractor rod, the rear where an extension of the extractor rod fit into the face of the recoil shield and a third place on the yoke where it meets with the barrel. This provided for a very sturdy and repeatable lockup, thus allowing both cartridge and revolver to extract the most accuracy. Up on the barrel, a shroud was provided to protect the extractor rod and add some recoil-dampening weight. The first .44 Hand Ejectors became known as Triple Locks because of the three locking points. It was introduced in 1908 and available in 5″ and 6 1/2″ barrel lengths, chambered in .44 Russian and .44 S&W Spl. However, very few were made with 4″ barrels chambered in .38-40, .44-40 and .45 Colt.

Sales of the new .44s were disappointing to say the least, probably due to three factors. First, these revolvers recoiled more than the .38-cal. guns. Though considered paltry by today’s standards, the Modern Technique of the Pistol was still about half a century in the future. Most people still shot a handgun with one hand in what we now call a “duelist stance.” Too, because of the extensive handwork necessary to manufacture a revolver with three lockup points and the time required to evenly polish a barrel with an integral underlug, the retail cost was greater enough to spur many budget-conscious shooters to opt for the smaller caliber. Finally, the semi-automatic pistol was getting a lot of attention at the same time. A lot of “cutting edge” shooters of the day chose something newer than a rehash of existing technology. More than a century ago, as today, much of the gun-buying public clung to the arcane and false notion that “Where there is lead in the air, there’s danger!”

Smith & Wesson had a problem. Arguably its finest revolver wasn’t making it in the sales department, and it was costly to manufacture to boot. A Hand Ejector Second Model was introduced in 1915. The Second Model eliminated the third locking point in the yoke, along with the integral underlug. It was in production for just two years before Smith & Wesson had to make the switch to wartime production. The Hand Ejector Third Model came about in 1926 because of a heightened demand for the integral underlug on the barrel.

Wartime demands of World War II halted the manufacture of the 1926 Model in 1940. Once the world was once again made safe for a few years, the company brought out the Hand Ejector Fourth Model of 1950. Like its great, great grandpappy, the Model 1950 was not a stellar seller. Target shooters more often than not chose a lighter, easier recoiling .38 Spl. or a .45 ACP for their paper-punching chores. Buyers of the 1950 Model were largely restricted to savvy law enforcement guys, often in rural areas, and a group of revolver aficionados known as The 44 Associates, publicly led by a sawed-off Montana cowboy by the name of Elmer Keith.

This latter group made a name for themselves handloading the .44 Spl. to velocities never dreamed of by the cartridge’s inventors. Keith served as the blow horn for these efforts. In 1956, what appeared to be the final blow to the .44 Spl. was turned loose on the public—the .44 Remington Magnum. This cartridge did everything the .44 Spl. could do and then some, but at a cost. Those costs included an unacceptable amount of recoil for a fighting gun and an even heavier revolver to pack around.

A lot of law enforcement guys and backcountry wanderers clung to the Model 1950 but not enough to continue production. The Model 1950—by this time known as the Model 24—was discontinued in 1967, and according to the factory, no plans were in the works to reintroduce it. The supply of .44-Spl. S&Ws dried up faster than a spring rain in the desert.

***

Now let’s go back about 40 years. Some of you were not here yet; others, like me, still had all of our hair and it was dark. I was a gun-struck, wannabe pistolero with a whole lot of desire and energy and not much money. Working two jobs, virtually every spare nickel I made went into guns, ammunition and reloading components. I had bought my first handgun, a Colt New Frontier .22/.22 WMR just four years prior. During that first year I also bought my first two center-fires, a Smith & Wesson Model 27 and a used Series 70 Colt Government Model. Although fascinated by firearms back to my earliest memories, I had not really grown up around guns. My family was not into guns and hunting, so my interests sat famishing until I was old enough to buy my own.

Like a lot of guys back then, my mentors were writers in gun and outdoor magazines. Part of my gun money went to subscriptions and books to help me along in my self-education. One guy who struck a chord with me was Charles A. “Skeeter” Skelton, a law enforcement and cowboy type out of New Mexico. Skeeter was a Depression-era kid who found adventure as a Marine in World War II, and later as a Border Patrolman, Sheriff and U.S. Customs agent. He had a deep appreciation and knowledge of handguns and was a gifted storyteller. Skeeter wrote a handgun column for Shooting Times back when it was a part of PJS publications. The reason I had a Model 27 and a Jordan holster on a River Belt by Don Hume was because of Skeeter.

While the Model 27 and its .357-Mag. cartridge were plenty good—especially for a kid with little experience—Skeeter’s prose regarding revolvers chambered for .44 S&W Spl. kept me pretty goggle-eyed. His stories of adventures—and a few pratfalls—with a .44 on his hip had me pining deeply for a .44 Spl. Trouble was, Smith & Wesson had discontinued the .44-Spl. chambering and its Model 24 about a dozen years prior to my discovery of it. I haunted gun shops from Sacramento to San Diego searching for one. In one year, I found exactly one, a 6 1/2″ barreled Model 24 in a gun shop in Orange County, Calif. The price was $750, more than twice the going rate for a Model 29 .44 Mag. that was nearly as scarce.

Then—I believe it was in one of Skeeter’s columns—I found that Bob Sconce of the Miniature Machine Co., had a few original 6 1/2″ 1950 Target barrels available. These were pre-Model 24 barrels, raw and unpolished. If I recall correctly, Sconce was getting 125 bucks per copy. That was still pretty steep, but considerably less than $750. I gritted my teeth and came up with enough scratch to get one. Now all I had to do was find an N-Frame Smith & Wesson and get someone to marry the two.

At a local gun shop I found a barely used Model 28 Highway Patrolman for less than a pair of C-notes. Donor gun and barrel in hand, I began my search for someone who could meld the two into a desirable six-gun. Sconce had taken ill and was unable to work. I was about a year from making my move to Wyoming when I found a pistolsmith by the name of Tim LaFrance.

Like most good gunsmiths, LaFrance was backordered in work—four months, he said. Eight months later I still had not heard anything. I called him, and he said he would have it done in a month. Two months later I had the converted .44. LaFrance had fitted the barrel and rechambered the cylinder. I also had him shorten the barrel to 5″ to match my Model 27 and reattach the ramp and front sight. Fortunately, the barrel markings were centered at the 5″ length, so it looked almost factory made. I found another guy—whose name escapes me after four decades—to completely refinish, polish and blue the gun. I finally had my .44 about a month before I migrated to Wyoming.

First thing on the agenda was to acquire loading dies, a bullet mold and some .44-Spl. brass—a fairly tall order for a 25-year old on an extremely tight budget. I finally scrounged up what I needed. The dies were used and made by Eagle; the mold was a dual-cavity Lyman 429421 that threw 245-gr. semi-wadcutters. Then I got to cranking out some ammo. I tried several loads, but two were clearly standouts, and they were just about standard among .44-Spl. aficionados; 7.5 grains of Unique, a load that now is commonly known as “Skeeter’s load,” and 17.5 grains of 2400, which was Keith’s hunting load prior to the standardization of the .44 Mag. Both of these, I should point out, are no longer listed in any modern loading manual I am aware of. The claims that Alliant has changed its formulas or burn rates have not been substantiated, so I assume that it is more of an erring on the side of caution. I would not try either of these loads in a Smith & Wesson revolver made before 1950.

My custom .44 never got to be the centerpiece of any adventures paralleling Skeeter’s, but it did provide for an occasional meal on the trail, and it rode in the same Jordan holster during my short stint as a police officer in Afton, Wyo. I won a few informal pistol matches with it. One afternoon a friend and I were shooting revolvers—my custom .44 and his, an early post-war M&P which I now own.

After a while, shooting paper got to be a bit uninteresting. I was getting a bit cocky so I turned the .44 upside down and began shooting at a stick on the ground using my pinky to operate the trigger double action. The stick bounced at every shot. My friend—who has now long gone to his reward—snapped “Smart aleck!” or something similar. He picked up the stick and threw it in the air saying, “Hit this!” With the revolver right side up now, I tracked the stick and pulled the butter-smooth double-action trigger. To our mutual astonishment, the damn stick was severed in the middle.

Life’s tribulations forced me back to California a few years later, and one time I was bouncing along on a ranch in the western Sierras with another friend. My .44 was safely tucked away in the Jordan holster when suddenly a wild pig came boiling out of a shallow depression in the grass. The horse I was riding—not mine—was a bit unaccustomed to having wild pigs jump up nearly between its feet. I made a sort of flying dismount with assistance from that horse and drew the Smith, tracking the offending porcine at about 35 yards. The revolver bucked and the 90-lb. sow slid on her nose.

Smith & Wesson’s declaration of never producing the Model 24 (or 1950 Target) proved a bit premature. In the 1980s Lew Horton commissioned the company to make a limited run of Model 24-3 revolvers with a round-butt, K-frame grip profile. I wasn’t about to let this get away, and soon one of these became a regular companion. Still later, I found a 4″ barreled Model 24-3 in unfired condition on Gunbroker.com. When it arrived, I remedied the unfired condition situation quickly. Still later, I acquired a Colt SAA and a pair of Ruger Flat Tops in the proper caliber. The Colt has taken a pig and a deer, and I now feel adequately comfortable with my .44 S&W Spl. situation.

While not exactly commonplace, the dearth of .44-Spl. revolvers is not as dire as it was in the mid- to late ’70s. Charter Arms has its Bulldog, and here and there it is possible to find a Smith & Wesson or Ruger that does not force you to make the choice between the gun and a house payment. In fact, Ruger has the GP 100 available in .44 Spl. now. If you love revolvers but have not yet had the pleasure of an accurate, powerful and yet manageable revolver on your hip, better get one now. I bet you can’t stop with just one!

In the quiet times, one often wonders just why a so-called “popular” cartridge doesn’t quite make it to commercial or even best-selling wildcat status.

Maybe it’s the lack of publicity or the fact many gunsmiths or even shooters don’t know of the round or, worse yet, even care to tinker with it. Back in the beginning of the last century, many cartridges were out there in force, and through the space of time, the best of the best simply rose to the top.

There were some good designs that now you only read about in faded, dog-eared tomes of the past – those like the 2R Lovell, .22 Niedner or even the line of .22 Miller magnums. They were good because their inventors said they were, but at that time gunsmiths were seemingly hidden away in back shops all around America, and since we didn’t have the media exposure we do today, and unless you could get a following, all was lost.

Still others were variants of commercial rounds and made life somewhat easier. Experimenters of the day loved small, compact cases like the .218 Bee or the Hornet to modify, improve or otherwise boast about. Harvey Donaldson, for instance, took his lead from the .25-35 or .30 WCF case and came up with the .219 Donaldson Wasp.

The .22 Hornet received its “improved” status as the .22 K-Hornet, which like many others involved nothing more than fireforming the factory round in a K chamber. The .218 Bee was still another one, and from it grew the likes of the Gipson Improved, the Ackley Improved and the Mashburn version.

Being a big fan of .22 centerfires, I’m always on the lookout for same from custom gunmakers or commercial outlets. Most rifles can be found in the trade papers that run hundreds of ads for used guns, new guns and specialized services.

This one, however, came from the folks who built a tack-driving .221 Fireball for me a few years back. Cooper Arms (3662 Hwy 93 North, Stevensville MT 59870) is becoming known for preserving wildcats from the .17 Squirrel to improved versions of the .257 Roberts. Dan Cooper sent a new catalog, something dyed-in-the-wool wildcatters should have, and once I saw the selection, I was hooked.

The company has several actions set up for different cartridges, lengths and rifles. My particular favorite is the Model 38, which can house all the really neat wildcats like the .17 Ackley Hornet, .17 He Be, .19 Calhoun and the .218 Mashburn Bee.

For the varmint folks, you have a choice of versions that include the varmint-type rifle complete with a heavier barrel and flat forend stock. Those who like the more classic type rifle can order theirs in the Classic, Classic Custom and Western Classic complete with a variety of options to include a skeleton grip cap, skeleton buttplate and checkered bolt knobs, among other things. Wood is anything from AAA select Claro walnut to AAA French walnut.

I selected the Varminter, which is the basic custom type rifle but without any of the options. Prices for the Varminter, complete with the Model 38 action, depend upon options and wood. Workmanship is first-class, and all rifles shoot like a house a fire!

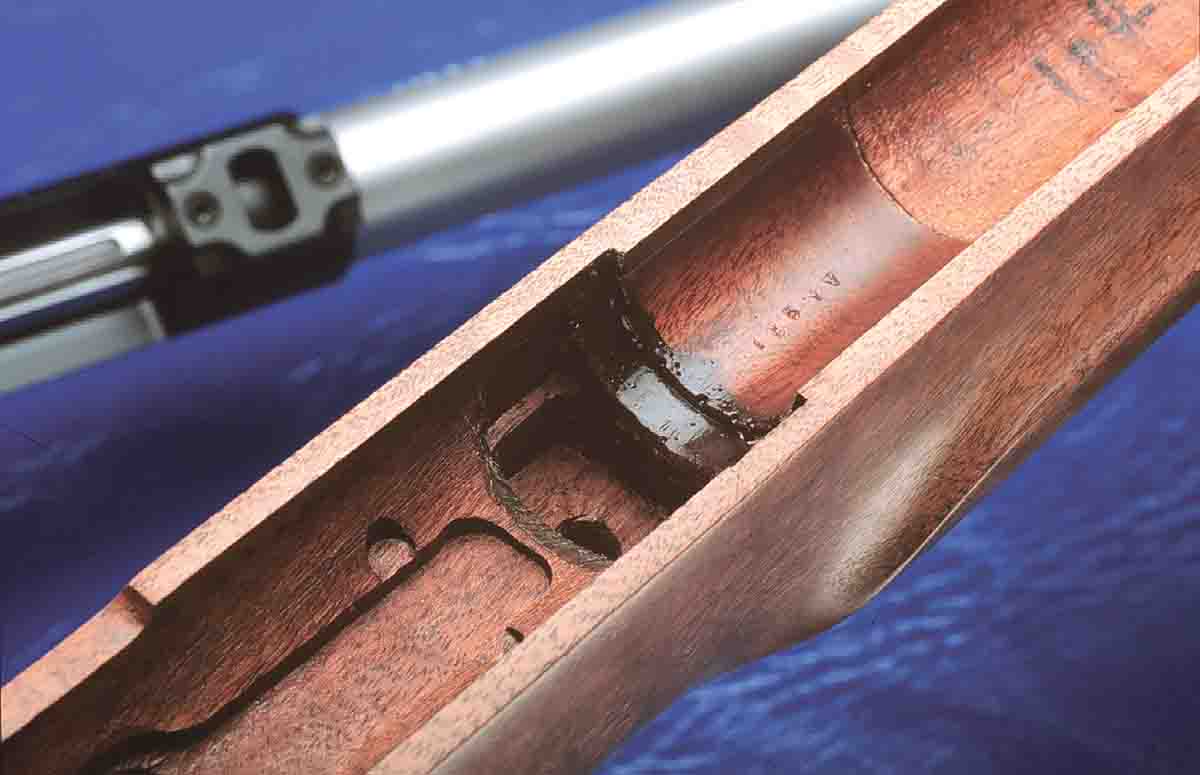

The first thing you’re going to notice about Cooper’s “varmint” series is that they don’t feel like those big, clunky varmint rigs you may have used in the past. Sure, there is a wide forearm, but it is designed to be a working part of the rifle and not a hindrance. Inside, you find the inletting of the rifle perfect; one thin sheet of paper will fit between the forend and the free-floating barrel.

There is no Monte Carlo or cheekpiece on the stock, and the line of sight between shooter and scope is right on. The pistol grip has that just-right downward turn for prone shooting and is finished without a grip cap on this model. Point checkering is included, as is a rubber buttpad for non-slip performance in the field.

The action is the heart of any rifle, and Cooper’s version is glass bedded about the recoil lug. Barrels are air-gauge inspected and match-grade quality. The bolt has three lugs, and the trigger pull from the factory was set at 21⁄2 pounds without any hint of slack or creep.

The action is single shot and includes an innovative feed ramp. It is set up to move in a rocking fashion as the cartridge is fed into the breech. In this way it will move when the bullet, shoulder and cartridge move into the chamber, giving the action an uncanny smoothness.

In fact, this altered ramp will even feed empty cases into the breech to check for the final headspace and bolt resistance on a sized case before getting set up for loading. Finally, the safety is rearward of the bolt handle, and scope bases (included) accept all the commercial rings in Redfield-style bases.

The .218 Mashburn Bee

A.E. Mashburn of Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, designed the .218 Mashburn Bee. In all likelihood it is the most popular of the modified Bees, even though it has the most severe case modification. The Bee case, for all practical purposes, has a 17-grain capacity, and since it matched the 2R Lovell for the same ballistics, loads and performance, and with brass readily available, the 2R Lovell was placed on the back burner while the Mashburn version enjoyed an upward trek on the popularity scale in the 250-yard class of smallbore cartridges.

Like the .22 Hornet and .22 K-Hornet, the .218 Mashburn Bee is easy to form as long as you have a rifle to do it in. Just pop a .218 Bee into a .22 Mashburn Bee chamber, pull the trigger and, voilà, you have a new cartridge. Of all the so-called Bee versions of improved cartridges, the Mashburn moves the shoulder forward quite a bit, but while fireforming over 200 cases, I found that neck and mouth splitting were held to a minimum if the rifle has correct chamber dimensions. I had four that split at the shoulder and two of them had twin splits within close proximity of each other. Annealing in all probability could help, but for only four cases (around 2 percent), I didn’t think it was worth the effort.

Don’t expect this cartridge to be a barnburner; a modest 10 to 15 percent gain is just about right for this version over its parent. But if you’re looking for a wildcat that is easy to form, easy on the shoulder and just plain fun to shoot, the .218 Mashburn may be for you. Then again, if for some reason you get tired of this variation or run out of handloads, a few boxes of .218 Bee ammunition will put you back in business. Besides, you can always use more fireformed brass.

For a shopping list, purchase at least four boxes (200 cases) of factory ammunition or .218 Bee brass. I prefer the factory ammunition as this makes fireforming much easier in the initial stages of load development. Winchester is the sole supplier of brass and the only firm that produces it on a semi-regular basis.

Next a full-length die set is in order simply because the rifle will be forming it for you. I had RCBS forward a set of its number 56030, which is in the G group. The shellholder is RCBS No. 1 and Small Rifle primers like the CCI 400, BR-4 or Remington 71⁄2 Benchrest will fill the bill. No magnum primers are needed here, even if the weather turns cold.

With an ample supply of fired cases, I smoke a couple of cases with a candle so I can monitor the progression of the die as it works its way down the case neck. Then the die is secured to size the whole batch of cases. One nice thing about the improved Mashburn is overall length without the bullet measures the same as the parent .218 Bee – 1.340 inches.

After fireforming for the Mashburn, don’t be surprised if the case turns out to be only 1.320 to 1.322 inches in length. This is not surprising, as most “improved” cartridges are a bit shorter than the parent case after fireforming.

When working with a small case like the Mashburn, it’s a good idea to use the case lube very sparingly. The right amount of lubrication on the case should feel slightly tacky; anything more will lead to shoulder dents and/or neck splits.

After running a bunch of cases over the pad, place a small amount of case lube between your forefinger and thumb and go around the neck, keeping the lube at a minimum. Using a Q-tip, place a small amount of lubrication on the inside of every fifth case to aid in the withdrawal of the expander plug as it exits the case. With this technique, you’ll wind up with no damaged cases or dents when sizing.

Finding loads for the .218 Mashburn Bee took some research. While it does match the 2R Lovell, I like to find actual data pertaining to the cartridge I’m working with even if one closely matches it. To do otherwise would be foolhardy, especially when reloading ammunition.

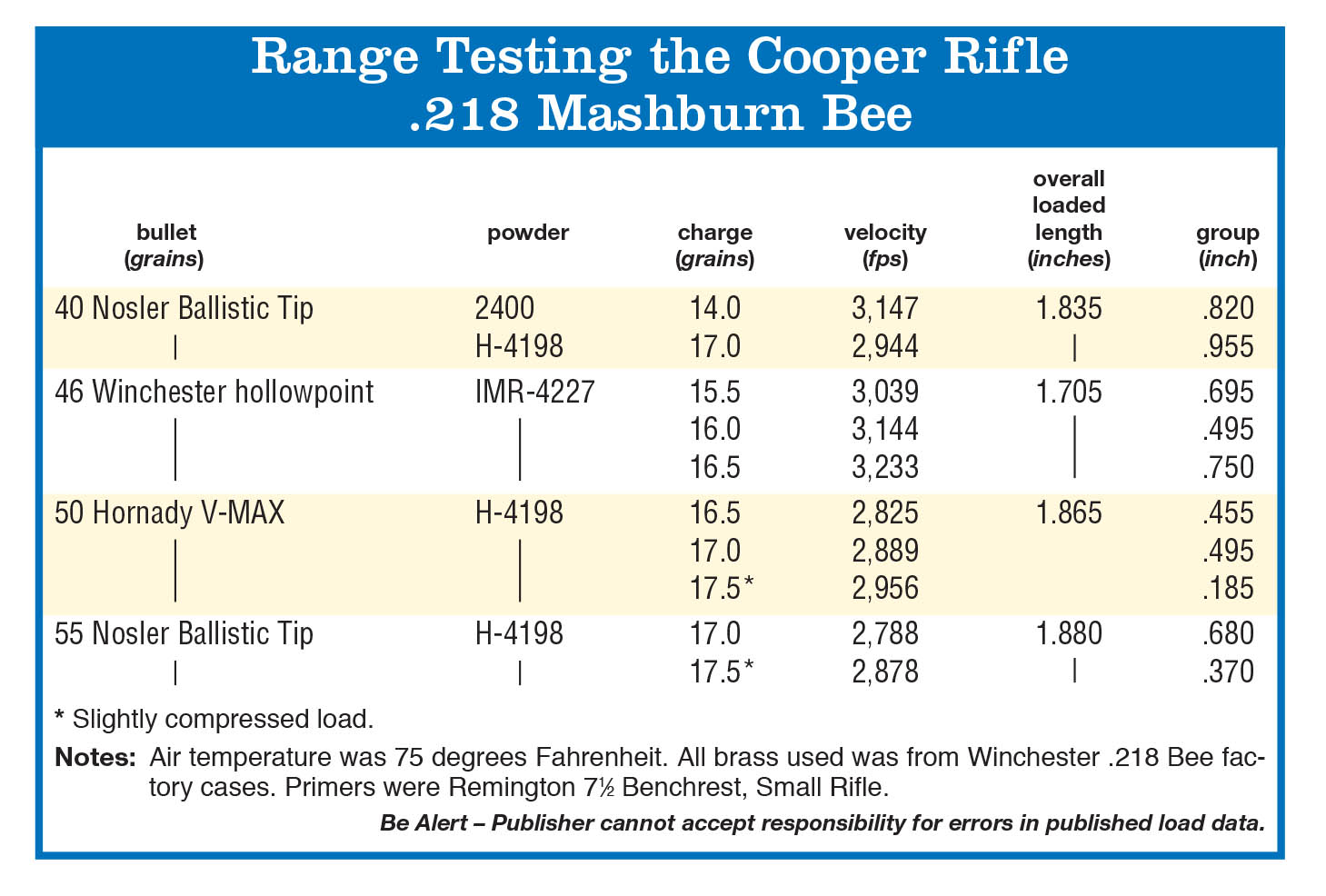

Vintage books from authors like F.C. Ness, C.S. Landis, Parker Ackley and briefs from our own Ken Waters helped to define the parameters of this Mashburn and set me on the right track. If you don’t have access to any of these, starting out with basic .218 Bee data will put you in fine shape with room to grow upward to around 10 percent for starters. The data listed is safe, accurate and gives velocities that go hand in hand with the volume and overall size of the .218 Mashburn Bee at responsible distances.

Powders included Alliant 2400 (which is great Hornet, K-Hornet or .218 Bee fodder), H-4198 and IMR-4227. All seem to fit this cartridge perfectly. Keep in mind, the .218 Mashburn Bee is a no-nonsense, .22-caliber cartridge that is capable of velocities from around 2,600 to 3,300 fps with lighter bullets and a slight drop in overall velocity with heavier bullets in the 50- to 55-grain class.

When loading small capacity cases like the Bee, care should be taken to see to all the details. For instance, some of the powder funnels made today seem to be just a little large for .22-caliber case mouths and especially for those with short necks. When this happens, small amounts of powder will fall outside the case. This can easily be verified by checking the inside of the tray you are using. Sometimes it can be as much as a full grain. The remedy is to use a .17-caliber funnel to make sure all the powder winds up in the case.

Volume with different powders showed that 2400 filled the case between the shoulder and neck with 14.0 grains. Using 17.0 grains of H-4198 placed the powder volume halfway up the neck. On the other hand, 16.5 grains of IMR-4227 was easier to use and because of its almost spherical qualities (as opposed to the stick type H-4198) filled the case to the neck/shoulder juncture of the case. Some of the loads that run upward of 17.5 grains of H-4198 filled the case to the brim and were compressed, but I had no problems seating any of the bullets from Hornady or Nosler.

Bullets ran from the almost petite Nosler 40-grain Ballistic Tip to the 46-grain “Bee” bullet from Winchester. This is the same bullet used in factory loads sans the cannelure. From here I filled out the list with Hornady’s 50-grain V-MAX, which is a favorite in just about all my .22-caliber firearms, and the ever popular Nosler 55-grain Ballistic Tip. I have also listed the overall loaded length, which is the length that is comfortable in the Cooper rifle and allows the full neck length to grip the bullet.

Looking at the table, the cartridge and the Cooper rifle did more than their part in this marriage. Alliant 2400 pushed a Nosler 40-grain Ballistic Tip over 3,147 fps with groups under an inch. For smaller, much lighter weight game, this just could be one of the best around for closer-range shooting. I’ve used the .218 Bee with a 40-grain bullet previously and, depending upon the powder, got velocities around 2,900 fps. So the 2400 load is an improvement.

In the 46-grain offerings, I used the Winchester “Bee” hollowpoint. With IMR-4227 I varied the loadsby .5 grain, each starting at 15.5, 16.0 and 16.5 grains. With the first selection, groups ran .695 inch at 3,039 fps. (This compares favorably to a load in the 2R Lovell that was quoted at around 3,260 fps.) With 16.0 grains, groups shrank to .495 inch with a mean velocity of 3,144 fps. Ackley quotes 3,242 with this same load. Finally, with 16.5 grains of IMR-4227, velocity increased to 3,233, but accuracy did suffer at .750 inch.

Since I started to see the beginnings of an extractor burnishing on the case head, I backed off and was more than happy with 16.0 grains. It’s more accurate anyway. Ackley published this load at 3,319, so again we’re close.

The 50-grain Hornady V-MAX was teamed with H-4198. With a starting load of 16.5 grains, groups fell into a boring routine of less than .5 inch at 100 yards. Seventeen grains did the same (around .495 inch), but when I turned to 17.5 grains, things did an about-face. This is a slightly compressed charge, so don’t panic when you fill the case.

The bullet seats easily, meaning there is a lot of air in the case with this propellant. This load at 2,956 fps turned in groups that averaged .185 inch – very impressive for a cartridge everyone seems to have forgotten. For the record, Ackley in his tome relates this load produced just about 3,300 fps. In the more common .218 Bee, I’ve gotten velocities of around 2,500 fps with groups that went slightly over an inch in a Ruger Model 77 with a 26-inch barrel.

Turning to Nosler again, I used its 55-grain Ballistic Tips. With 17.0 grains of H-4198 groups measured .680 inch with velocities around 2,800 fps. The final load of 17.5 grains was slightly compressed, hitting 2,878 fps (Ackley publishes this at 3,316 fps) with accuracy at .370 inch. I’ll take that any day.

The Cooper rifle and the improved Mashburn performed well time after time. The rifle is a joy to carry around considering it is a “varminter,” and combined with the Leupold 40x scope and a pocketful of Mashburn cartridges, it would be a great way to spend many a day stalking varmints in any part of the country. The loads took some time to research as not to err on the wrong side and, considering the effort, expense and fun, were indeed worth every minute.

To me any wildcat is worth it simply because you’ve separated yourself from the rest of the pack and struck out on your own. The .218 Mashburn Bee is a great place to start.

Rise and Fall of The 6.5 Creedmoor

About old ammo

Long-time hunter Craig Boddington takes an honest look at new cartridges that are essentially remakes of old cartridges. Are they worth it? Some are; some may not be.