Category: All About Guns

A place worth going to

It was London, it was September, it was raining.

Outside the Brigade of Guards Museum, near Buckingham Palace, the statue of Field Marshal Earl Alexander of Tunis stands 15′ high—a tribute to Britain’s greatest field commander of the 20th century. His trademark sheepskin is faithfully reproduced in a half-ton of bronze, and even here he manages to wear it like a dinner jacket. England’s greatest combat soldier was also known as the best-dressed man in the regiment.

As the rain pelted harder, plastering the brown beech leaves to the paving stones and forming tiny waterfalls in the creases of the jacket, Alexander—or “Alex,” as he was known to all—took no notice. He kept his eye fixed firmly on the entrance to the museum, and suddenly that seemed like a heck of a good idea as the sky opened up and the cold rain came down in sheets.

The Guards regiments are among Britain’s most famous icons. They are the soldiers in red tunics and black bearskins who mount the guard on Buckingham Palace, among other places. What is less well-known is that they are also elite soldiers who have fought the king’s wars around the world for centuries. The oldest regiment is the Scots Guards, followed by the Grenadiers and the Coldstreams. The Irish Guards—Alexander’s regiment—and the Welsh are the youngest.

Inside the museum, one tableau after another depicts their exploits at Waterloo, Dunkirk, South Africa, Flanders. The displays, colorful at first, turn slowly sodden and muddy as all the gentility was wrung out of warfare, and red tunics were replaced by khaki (in South Africa) and brown service dress in the mud of Flanders. The display from the First World War includes bits of webbing, barbed wire, grenades, a bayonet. The stuff looks muddy even when it isn’t.

There is also a rifle. Not a Lee-Enfield, No. 1 Mk III, as might be expected, but a classic single-shot, break-action rifle of the type favored, before the war, for stalking stag in Scotland. It is of obviously fine pedigree, but has seen much hard use. The bluing is worn to a silver sheen and the stock is scratched and battered.

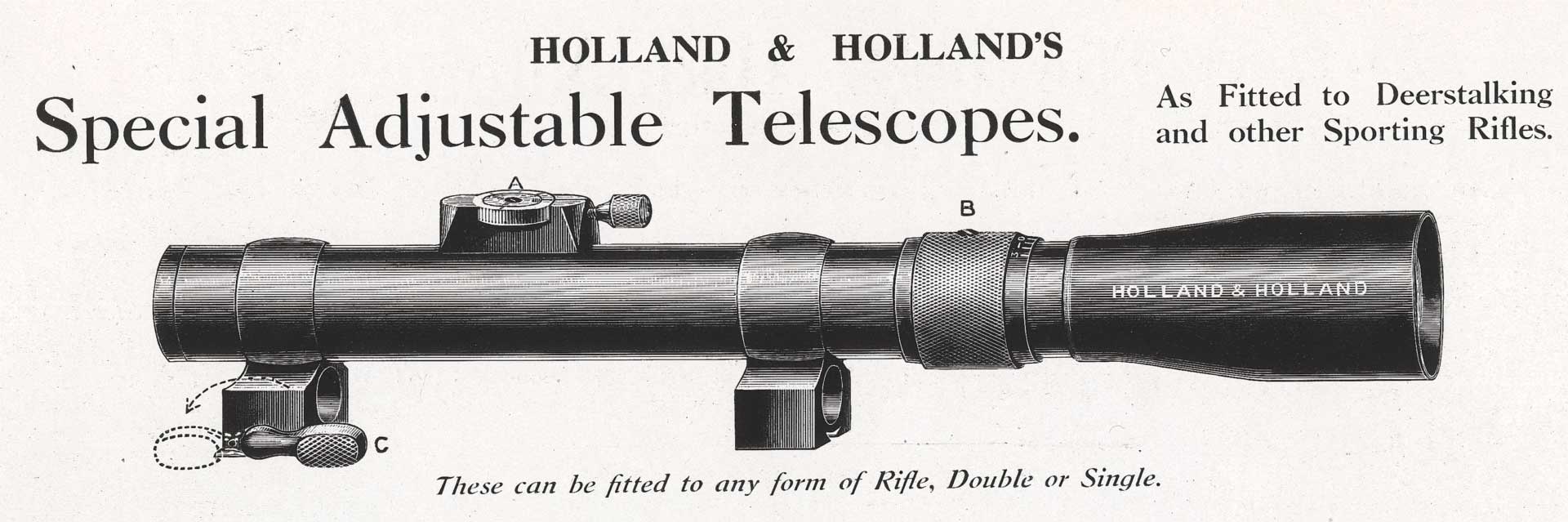

If you crouch down and peer closely, with the light exactly right, you can still read on the receiver “Holland & Holland.” It is an aristocrat among firearms, a “gentleman’s rifle”—a Royal Grade single-shot stocked in English walnut and finely checkered. At one time, the receiver displayed graceful engraving, although it is now worn almost completely away. Four years of trench warfare will do that.

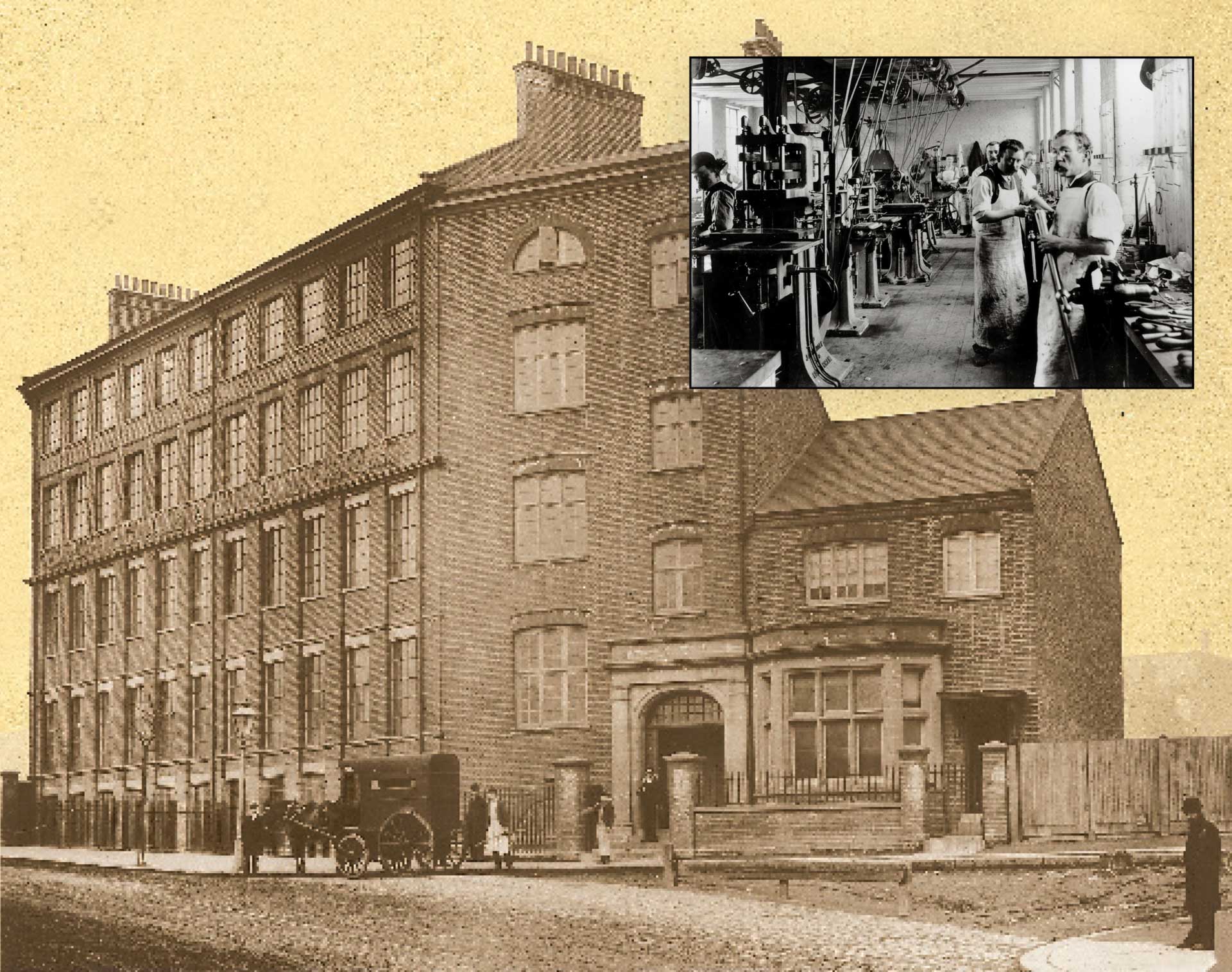

The story of how H&H rifle No. 26069 journeyed from the Bruton Street showroom to the Guards Museum is really one of convergence of the great names in pre-war England, in the military, in literature and in gunmaking. It involves Harold Alexander, Britain’s greatest soldier of the 20th century, and Field Marshall Lord Roberts, one of its greatest of the 19th; it involves Rudyard Kipling, Poet Laureate of the Empire and winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature; and of course Holland & Holland, England’s greatest riflemaker.

The story begins with Lord Roberts in South Africa, fighting the Afrikaners in Britain’s first, and one of its bloodiest, military campaigns of the 20th century. There, Roberts renewed his acquaintance with Rudyard Kipling, an old friend from India.

Roberts was an Ulsterman, a gentleman of Anglo-Irish descent. For reasons no one has adequately explained, Ulster (Northern Ireland) has produced a disproportionate number of great British generals. The Duke of Wellington was an Ulsterman, as was Montgomery, among many others. In the South African campaign, the army’s Irish regiments performed spectacularly. To recognize their contribution, Queen Victoria ordered—on Roberts’ advice—the formation of a regiment of Irish Guards to join the Scots, Grenadiers and Coldstreams.

When he heard the news, Harold Alexander (also from Ulster) was 9 years old. He immediately decided that his future would lie with the Irish Guards. The son of the Earl of Caledon, he attended school at Harrow, went on to the military academy at Sandhurst, and joined his new regiment in London in 1911. He was a 22-year-old first lieutenant when the war broke out in 1914.

One of his fellow officers was the Earl of Kingston, and they shipped off to France together. In the Earl’s kit was the H&H rifle. It came to be there in a rather convoluted way.

As war in Europe approached, many Germans made last-minute visits to London to order rifles from the English gunmakers. One ordered a stalking rifle, and even provided a fine Voigtlander scope to be mounted on it. Ordered in 1913, it was barely finished when the Germans marched into Belgium. H&H could not ship a rifle to an enemy country, so the firm re-barreled the rifle to .303 British and fitted it out as a sniper rifle. A member of Parliament, Colonel Hall Walker, bought it and passed it on to Lieutenant the Earl of Kingston of the Irish Guards.

Recruit No. 26069 was in the quartermaster’s stores when the regiment went into action for the first time and was still there, amid the chaos of retreat, advance and retreat, before the war settled down to the hell of the trenches. By that time, the Earl of Kingston had been wounded and invalided back to England. Alexander fought with the regiment through the Retreat to Mons, was wounded in the First Battle of Ypres and returned home to convalesce. What happened then can be pieced together from scraps of information that have survived.

From the hospital, Kingston wrote to the commander of the battalion, Jack Trefusis, inquiring about his rifle. On January 6, 1915, Trefusis replied:

“My dear K.

It has been in QM Stores for ever so long and I have only just this moment heard of it. It was a thing we have wanted badly for a long time, and if we had only known of it in the last trenches we were in I have no doubt we should have accounted for a platoon of Germans. However we go back into the trenches on Friday and the rifle will be put into the most skillful hands I can find and a careful account of the bag that is made with it which I will report to you occasionally … .”

The war was then barely four months old and Trefusis’s last paragraph is chilling:

“There is no officer here who was here with you except myself and Antrobus, and very few men. Poor Eric Gough was the last and he was killed last week.

“P.S.: I see I have never actually thanked you for letting us have the rifle, but I do enormously, it will put us on a more equal footing with those damned snipers, who are just as bad here as ever they were.”

As a military art form, sniping goes back several centuries, but it really flowered during the American Civil War. Not by coincidence, this was the first large-scale conflict in which trenches were used; trenches and snipers go together like coffee and cream. In the case of the British Army, through the late 19th century it fought mostly wars of movement until encountering the Boers in South Africa in 1899. Sniping was not a major factor, and while the British Army underwent a drastic reformation as a result, and became the best army of its size in the world, it still paid scant attention to sniping as it went to war in 1914.

Not so the Germans. When the German Army invaded Belgium, it had an estimated 20,000 sniping units ready to go. The Mauser Model 98 made an ideal sniper rifle; as well, when hostilities began the Germans collected thousands more accurate sporting rifles and sent them to the front. The British had but a handful of trained snipers, and few rifles with which to snipe. The German Army very quickly dominated “No Man’s Land” and the forward British trench lines. Trefusis’s rueful letter to the Earl of Kingston gives an idea of the havoc wrought by the German snipers.

When H&H rifle No. 26069 went into service with the Irish Guards and began to take its toll on the Germans, the call went out for more of the same. The War Office in London turned to H&H and the other fine rifle makers with orders for sniper rifles.

At the time, British gunmakers made three types of rifle: doubles, single-shots and bolt-actions. The doubles were mostly big-game rifles for Africa and India; bolt-actions went to the colonies, while single-shots—both break-action and falling block—were the classic stalking rifles for stag in the Scottish Highlands. As such, they were built to be accurate. Since the supply of Oberndorf Mauser actions had dried up for the British, they naturally built their sniping rifles to patterns like No. 26069.

A major problem was the supply of telescopic sights, and here the Germans, with their advanced optics industry, had a huge advantage. The War Office went so far as to try to smuggle scopes out of Germany by various underhanded means, but without notable success. This remained a problem until 1916, when British companies, like Aldis (of rangefinder fame), became capable of supplying telescopic sights in reasonable quantities. Until then, the gunmakers made do with whatever they had in inventory or obtained from civilian sportsmen.

The work went slowly at first, and by July 1915, H&H had fitted out only 10 more sniper rifles. Gradually, however, the pace picked up.

Another problem facing troops on the Western Front was the fact that German snipers concealed themselves behind pieces of armor plate. Early in the war there was little in the way of armor-piercing ammunition for standard rifles, and, again, the War Office turned to the London gunmakers. Figuring that any gun that could handle a Cape buffalo would punch through armor plate, Holland’s and the others shipped over 2,000 so-called “elephant guns.” These were a mixed blessing. While they demolished the armor well enough, the loud report combined with the smoke and belching flame revealed the shooter’s position to the enemy and brought down a rain of return fire.

Meanwhile, as H&H et al worked behind the scenes, rifle No. 26069 slogged on, killing Germans. Two weeks after his first letter to the Earl of Kingston, Jack Trefusis wrote again:

“The rifle has been an immense success and every Commander from C-in-C downwards has sent down to ask me about it, with the result that two are to be issued to each battalion.

“The sergeant major uses it and the score of Germans is for certain four killed and eight wounded in three days use … . Those who were killed or wounded were fired at from a range of 800 yards. So it has been a great success.”

In March 1915, recovered from his wound, Lt. Alexander was promoted to captain, helped to form a second battalion of Irish Guards and returned to France commanding its No. 1 company. One of his officers was a subaltern named John Kipling.

Lt. Kipling was Rudyard’s son. Denied a commission because of his poor eyesight, the novelist appealed to his old friend Lord Roberts, who was now Colonel of the Regiment of the Irish Guards. Roberts’ influence was still immense, and he obtained a commission for the boy. Within a month, the battalion went into action at the Battle of Loos, where 800,000 men were ordered to breach a German position after a four-day bombardment by 1,000 guns. Five days and 45,000 casualties later, the attack was called off.

The unit that penetrated deepest into German territory was No. 1 Company of the 2nd Irish Guards under Captain Harold Alexander. When they withdrew, they left the body of Lt. John Kipling, shot through the head. He was one of 10,000 British soldiers whose bodies were never recovered from the all-swallowing mud of that battlefield.

In deep sorrow, and as a memorial for his son, Rudyard Kipling, Britain’s foremost author, agreed to write the official history of the regiment, The Irish Guards in the Great War, and the “telescope rifle” found its way into literature:

“Casualties from small-arm fire had been increasing owing to the sodden state of the parapets; but the Battalion retaliated a little from one ‘telescopic-sighted rifle’ sent up by Lieutenant the Earl of Kingston, with which Drill-Sergeant Bracken ‘certainly’ accounted for three killed and four wounded of the enemy. The Diary, mercifully blind to the dreadful years to come, thinks, ‘There should be many of these rifles used as long as the army is sitting in the trenches.’ Many of them were so used: this, the father of them all, now hangs in the Regimental Mess.”

Alexander and the Irish Guards also saw action at the Somme and Passchendaele, Cambrai, the retreat from Arras and, finally, Hazebrouk. In this battle, Alexander commanded the second battalion and helped save the channel ports from German attack, but the battalion was annihilated as a fighting force.

Rifle No. 26069 soldiered on with the 1st Battalion, accounting for who knows how many German soldiers. It helped win the sniping war, and the men of the Irish Guards came to love the trim little “gentleman’s rifle” because it saved so many of their lives. In 1918, it was retired from active service and given a place of honor in the regimental officers’ mess before being turned over to the Guards Museum.

There, it became part of a permanent display depicting the valor and the unspeakable horror of the war on the Western Front. And there it was, that rainy morning in September, when I took refuge from the London weather by ducking into the museum. When I emerged after a couple of hours, the weather had cleared and it was breezy and cool. Alexander’s statue, so stern in the rain, now appeared to be smiling in the sunshine.

During the Second World War, when he rose to the rank of field marshall and commanded the Allied advance up through Italy, Alex was always cheerful, always a gentleman, no matter how bad things became. When you have men like George Patton under your command, I expect good humor is invaluable. The plaque on the statue describes him as Britain’s finest battle commander of that war. Montgomery would have disagreed, but Alexander would have smiled and shrugged. His tombstone reads merely “Alex”; longer names are for lesser men.

I strolled along Bird Cage Walk, through St. James’s Park and up toward Mayfair. It is a pleasant walk up to Berkeley Square and 31-33 Bruton Street, home of Holland & Holland. The former director of the firm, David Winks, was waiting for me on an upper floor where the company’s own collection of classic guns resides.

Winks was in charge when the curator of the Guards Museum approached H&H in 1992 and asked them if they would take rifle No. 26069, much battered by the war and deteriorated after 75 years of benign neglect, and return it to its former glory.

David Winks agreed to clean it up but flatly refused to return it to pristine condition, although it could easily have been done.

“Those are honorable scars, honorably earned,” Winks told me.

“It would have been wrong to touch it.”

Shooting the AK-47

In the late 1880s, the lives of settlers on the Cumberland Plateau of Tennessee had changed little since before the Revolution. Lofty mountains, bridgeless streams, and unpaved roads had isolated the mountain folk from the affairs of the outside world for over a century. Their education and smarts came not from books and “larning,” but from their intimate knowledge of the rugged outdoors. Fiercely independent and self-reliant, they made do with whatever nature and the good Lord provided.

Alvin Cullum York was brought up in these backwoods, where hard work on the homestead made for robust constitutions and where stealth and expert marksmanship in the wilderness were vital for fetching wild game for food sport.

Born on December 13, 1887, Alvin and his ten siblings were raised in a two-room log cabin in Pall Mall, Tennessee, within spitting distance of the Kentucky state line.1 There, in the sun-drenched valley of Three Forks of the Wolf River, the Yorks tended to their seventy-five-acre farm, “part level and part hilly,” where they grew corn and raised chickens, hogs and a few cows for their subsistence.2 To make ends meet, his father, William, worked as a blacksmith, setting up shop in a mountain cave near their home. His mother, Mary, would do chores at neighbor’s homes, sometimes accepting old clothes as payment, which she would mend and alter for the children.3

York family log cabin. From Cowan, Sergeant York and his People, 33.

York family log cabin. From Cowan, Sergeant York and his People, 33. Valley of the Three Forks O’ the Wolf. From Cowan, Sergeant York and his People, 89.

Valley of the Three Forks O’ the Wolf. From Cowan, Sergeant York and his People, 89.

Schools in the remote mountain regions were scarce and poorly funded, not that it mattered much for the older children had to help harvest the crops as a matter of priority. In the winter, keeping school open was impractical as many of the children had to travel long distances and lacked warm clothes and proper shoes. The one-room schoolhouse in Pall Mall was open for only 2 ½ summer months a year; Alvin attended three weeks a year for five years, receiving the equivalent of a second-grade education.4

Alvin picked up hunting skills from his father and his grit from stories of “fightin’ men” like Daniel Boone, Davy Crockett, and Andrew Jackson. For Alvin, hunting was not just a skill but an art. A man had to become intimately acquainted with his rifle’s parts, meticulous with its care, and familiar with its “temperament,” whether its fire would lean left or right or if the sun or the wind, dry or damp days would affect its performance. As an experienced hunter, Alvin could read and interpret signs left by wild animals, blend into the woodlands, and remain motionless while stalking his prey. At local shooting matches, with his old muzzle-loading “hog rifle,” he “could bust a turkey’s head at most any distance” and “knock off a lizard’s or a squirrel’s head from that far off that you could scarcely see it.”5

When his father died in 1911, York went “hog wild,” cussing and gambling and drinking moonshine, the latter often in challenges where the winner was the last man standing. He found himself in trouble with the law on more than one occasion.6 Although he never shunned his responsibilities at home, his sinful ways caused his ma many a sleepless night in prayer. In her quiet manner, she begged her son to change. As a Christian woman, she knew that his sins were wasting his life and destroying his chances for salvation. As a mother, she feared for his personal safety each time he went past the front gate.

Alvin, now twenty-seven years old, began to assess his life and often went into the mountains to pray and ask God to help him fight his demons. He started attending the Wolf River Church where a saddlebag preacher’s sermons further enlightened Alvin to a life of righteousness. His growing fondness for Gracie, a local beauty thirteen years his junior and devout Christian, boosted his motivation to change. 7 On January 1, 1915, York swore off his vices and joined the Church of Christ in Christian Union. A fundamentalist sect, it opposed all forms of violence and advocated a strong pacifist philosophy which York adopted. 8 Now a devout Christian, his new-found beliefs were about to be tested.

Hints of War

On April 6, 1917, the United States of America formally declared war on the German Empire when German U-boats attacked U.S. ships in the Atlantic. Word got around Pall Mall about the escalating war, but little was understood about its causes, our involvement, or its objectives. “I knowed big nations were fighting, but I didn’t know for sure how many and which ones…I had no time nohow to bother much about a lot of foreigners quarreling and killing each other over there in Europe.”9

On May 18, the U.S. government enacted a law requiring that all able-bodied men between the ages of twenty-one to thirty-one register for the draft. York reluctantly registered on June 5 but attempted to gain status as a conscientious objector. Three separate requests for exemption from selective service, including one from his pastor and mentor, Rosier Pile, were summarily denied by the local and district boards. Their reasoning was that the church had “no especial [sic] creed except the Bible, which its members interpret for themselves…”10

Fentress County recruits, November 15, 1917. Alvin York is fourth from left.

Fentress County recruits, November 15, 1917. Alvin York is fourth from left.

From Hogue, History of Fentress County, xiii.

Throughout his time at Camp Gordon, York was deeply torn between the pacifist teachings of his church and a moral obligation to serve his country. He received counseling from his superiors, Captain Edward Danforth and Major Gonzalo Edward Buxton.11 They managed to convince York to reconsider his role in the Army by referencing chapters from the Bible regarding war and sacrifice. After spending a few days home while on leave, the young private returned to camp, convinced that serving his country was God’s will.12

York was assigned to Company G, 2nd Battalion, 328th Infantry, 82nd “All American” Division on February 1, 1918, and trained at Camp Gordon in Chamblee, Georgia, just northeast of Atlanta. Not surprisingly, he qualified as a sharpshooter when he was able to hit eight out of ten moving targets at 600 yards.13

Over There

The 328th Infantry shipped out from New York and arrived in Liverpool, England, on May 16, 1918, then moved on to Southampton, England, and Le Havre, France, where they landed on May 21, 1918. At Le Havre, their U.S. model of 1917 .30 cal. rifles were exchanged for British Mark III Lee-Enfield rifles, but they were able to keep their 1911 Colt .45 pistols.14 One month later, an assumption that the 82nd Division would be attached to British troops in the region of Picardy was overturned, and the 82nd was instead ordered to Toul. With that, the Lee-Enfield rifles, along with other armaments, were returned to the British and the U.S. model of 1917 Enfield bolt-action rifles were reissued.15

U.S. rifle cal .30, model of 1917 Enfield most likely used by Alvin York. Manufacturer: Eddystone.

U.S. rifle cal .30, model of 1917 Enfield most likely used by Alvin York. Manufacturer: Eddystone.

Courtesy Missouri Historical Society.

British Mark III Lee-Enfield Rifle. Courtesy National Army Museum, London.

British Mark III Lee-Enfield Rifle. Courtesy National Army Museum, London.

By then, the war along the Western Front had become a bloody stalemate with heavy fighting along a series of trenches stretching from the English Channel to the Swiss Alps. Reinforced by the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF), the Allies went on the offensive trying to break through German defenses in northern France.

From Le Havre, the 82nd Division traveled east by train and on foot, past idyllic small towns and serene countrysides, a cruel paradox of what was to come. On June 26 near Rambucourt, York heard the first sounds of gunfire “jes like the thunder in the hills at home.” At Mont Sec, bullets whizzed past “like a lot of mad hornets or bumblebees when you rob their nests.” Here he was placed in charge of an automatic weapons squad and shot French Chauchat machine guns, which he described as being heavy, clumsy, inaccurate, and noisy. “They weren’t near as good as the sawed-off shotguns,” he’d say.16 In September, York was promoted to corporal just before his regiment seized the town of Norroy.17

In the Valley of Death

1st Division Meuse-Argonne Offensive map compiled by American Battle

1st Division Meuse-Argonne Offensive map compiled by American Battle

Monuments Commission, 1937. Click map to enlarge.

On October 7, 1918, the 1st Battalion, 328th Infantry was ordered to take Hill 223, a strategic position just three kilometers southeast of their main objective: the Decauville rail line. This mission came during a critical phase of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive as American and French troops attempted to achieve the breakthrough that could end the war.18

On the night of October 7, York and the men of the 2nd Battalion watched and waited from the main road between Varennes and Fléville for their turn to continue the assault beyond Hill 223. At 0300 hours, bogged down by heavy rains and mud, fatigued from a sleepless night, hampered by a trek devoid of light except for the glow of gunfire hailing down around them, the troops slogged towards the hill amid utter chaos.

“Lots of men were killed by the artillery fire. And lots were wounded. The woods were all mussed up and looked as if a terrible cyclone done swept through them. But God would never be cruel enough to create a cyclone as terrible as that Argonne battle. Only man would ever think of doing an awful thing like that.”

At 0610 hours, York’s battalion along with three other companies of the 328th Infantry, pushed off Hill 223 with fixed bayonets. The advance was to be preceded by a rolling barrage of artillery fire that never came.19

As the troops raced downhill and charged across the 500-yard valley, now exposed with the light of dawn, an explosion of gunfire erupted from the heights above. “We had to lie down flat on our faces and dig in. And there we were out there in the valley all mussed up and unable to get any further with no barrage to help us, and that-there machine-gun fire and all sorts of big shells and gas cutting us to pieces.”

Valley just west of hill 223 across which York and the 2nd Battalion attacked on the morning of October 8, 1918.

Valley just west of hill 223 across which York and the 2nd Battalion attacked on the morning of October 8, 1918.

From Candler, History of Three Hundred Twenty-Eighth Infantry, 60.

The first wave of men had been decimated by the Germans, and now York’s battalion lay pinned down, able to move but a few feet at a time. Something had to be done, but a frontal attack was out of the question.

When platoon sergeant Harry Parsons realized that the thrust of the machine gun fire came from a ridge to the left, he ordered Sergeant Bernard Early to lead Corporals York, Savage, and Cutting and three squads totaling thirteen men, to silence the machine gun nest on the ridge. Seventeen soldiers stealthily climbed up the left flank, concealed by the thick undergrowth, slipped deep into German lines and encircled the enemy gunners from the rear. While chasing the first two enemy soldiers they encountered, the squads stumbled upon a German headquarters with fifteen to twenty unsuspecting soldiers and officers from the 120th Württemberg Landwehr Regiment in conference.20 Caught completely off guard, the Germans surrendered. While the prisoners were being searched, enemy gunners situated on the ridge above the camp turned their machine guns around and swept the open space, instantly killing six American soldiers, including Corporal Savage, and wounding three. Among the wounded were Sergeant Early and Corporal Cutting. Corporal York was now in charge with just seven men under his command.

The onslaught of machine gun fire from above was relentless and destructive. The German prisoners had hit the ground and the Americans had shielded themselves between them, some of the privates managing to get off a shot or two.21 York was caught out in the open about twenty-five yards below the machine gun line near the ridge, his men and the German POWs huddled behind him. Each time a German soldier raised his head, York would “tech him off,” just like he did at the turkey shoots back home.

Colt .45 government model of 1911. Garry James, American Rifleman.

At some point, York stood up and began to shoot his rifle offhand. His weapon was getting hot and he was running out of ammunition. So when a German officer led a counter-attack with six of his men charging towards York with fixed bayonets, York drew his Colt .45 automatic and, from back to front, shot each one, a practice he picked up at wild turkey shoots in Pall Mall. The idea was to hit the rear soldiers first so that the remainder would not see their comrade fall and fire at him. “It was either them or me and I’m a-telling you I didn’t and don’t want to die nohow if I can live,” he said.

Falling back on his hunting experience in Tennessee, York continued to methodically pick off German soldiers one by one, each time hollering for them to give up. Alarmed by the number of troops being shot dead and their shattered morale, the German commander, Lieutenant Paul Jürgen Vollmer, shouted out in English offering to surrender his troops.22 As the Germans began to emerge from the upper trenches, one fellow hid a grenade in his raised hand, which he threw at York but missed, hitting another prisoner. York reflexively shot him, and there was no further trouble.

York ordered the eighty to ninety prisoners to form two lines and had them carry Sergeant Early on a stretcher. Using them as cover, York placed Vollmer in front of him with his pistol trained on his back and the other two German officers on either side of him. Seeing that York was considering which way to go, Vollmer suggested to turn down a gully, but York quickly figured it was a trap and decided to go in the opposite direction. Since York and his men had captured the rear German line, they inevitably ran into the first line of enemy trenches. He succinctly told Vollmer to order them to surrender or he would blow the commander’s head off, and they did, joining the lines of POWs headed to the command post.23

York and his men marched the prisoners from one command headquarters to another against his men’s better judgement, until the captives were finally accepted at division headquarters in Varennes, a distance of 10 ½ kilometers. Altogether, York killed 20-25 enemy soldiers, neutralized thirty-five machine guns, and captured 132 German soldiers, though he was quick to reject full credit for the extraordinary success of his mission. “There were others in that fight besides me… I’m a-telling you, they’re entitled to a whole heap of credit. It isn’t for me, of course, to decide how much credit…But jes the same, I’m a-telling you, a heap of those boys were heroes, and America ought to be proud of them.”

His actions enabled the 328th Infantry Regiment to advance across the valley and capture the strategic Decauville Railroad. With their Army on the verge of total collapse and the Central Powers facing defeat on all fronts, Germany agreed to an armistice with the Allies on November 11, 1918, bringing the war to an end.

“I jes want to go home.”

Alvin C. York was promoted to the rank of sergeant on November 1, 1918. He received numerous American and foreign awards, including the highest recognition that could be bestowed upon a U.S. soldier, the Congressional Medal of Honor. French General and Supreme Allied Commander, Ferdinand Foch, commented to York, “What you did was the greatest thing accomplished by any private soldier of all the armies of Europe.”

When York returned to the United States, he found that he had become a national celebrity. It was all so overwhelming for the humble hero, but all he really wanted was to go home. He received offers from Hollywood and Broadway to adapt his life story into a movie and numerous endorsement deals and public appearances worth tens of thousands of dollars. York chose not to capitalize on his newfound fame. He once famously stated “This uniform ain’t for sale.” Instead he dedicated himself to his family and a number of charitable causes. He became a proponent for veterans’ rights, education, and economic development for his impoverished community. Seeking to raise money to help build a bible school, York finally gave his blessing for Hollywood to produce a film based on his life story. In 1941, Sergeant York was released in theaters, starring Gary Cooper in the title role that would earn him an Academy Award. It was the highest grossing film of the year, inspiring young Americans across the country to enlist in the U.S. armed forces during World War II.24

On September 2, 1964, Alvin C. York passed away at a veterans’ hospital in Nashville, Tennessee, at the age of 76. He is currently buried at the Wolf River Cemetery in his hometown of Pall Mall, Tennessee, next to his wife, Gracie, who passed away twenty years later.

Alvin C. York has maintained the status of an American folk hero whose story still resonates with Americans to this day. His heroism in battle, his legendary sharpshooting skills, his underprivileged upbringing, his faith in a higher power, his sense of patriotic duty, and his humble nature all contributed to the legend that is Sergeant York. His story is regarded as one of the most inspirational American success stories, and he has been memorialized as one of the greatest heroes in the long history of the United States Army.

Enfield vs Springfield Rifle Debate

Much discussion has centered around whether York used a 1903 Springfield or a 1917 Enfield rifle during the war. WW I munitions data presented by Assistant Secretary of War, Benedict Crowell, concluded that 12-15% of rifles issued were Springfield guns but the vast majority were 1917 Enfields.25

U.S. rifle cal .30, model of 1903 Springfield. Twelve to fifteen percent of rifles issued to WW I soldiers were Springfields. Wikimedia

U.S. rifle cal .30, model of 1903 Springfield. Twelve to fifteen percent of rifles issued to WW I soldiers were Springfields. Wikimedia

In his diary, York did not specify the type of rifle he used. Per Colonel Buxton, the 82nd Division was issued 1917 Enfields.26 In 2005, writer Garry James documented a conversation he had with York’s son, Andrew, who stated that his father had somehow switched his 1917 Enfield for a 1903 Springfield because the Enfield “had a peep sight with which York had difficulty leading a target.” Another individual commented on a forum that Andrew York told him that when his father’s unit reached the front, they were given a choice of one of the surplus ’03 Springfields, and that York switched, in part, because “the notched rear sight and post or blade front sight” were virtually the same as on his old muzzleloader. On both occasions, Andrew incorrectly stated that his father trained stateside on the ’03 Springfield and that these were replaced with Eddystones at Le Havre (Woodsrunner 38 second entry). A third forum commentator who also met Andrew York questioned Andrew’s knowledge base on the subject. (See Scott in Indiana). Regardless of which rifle he used, Alvin York’s extraordinary feat is well documented and undeniable.

Video

Words spoken by York voiceover actor are directly from his diary. Great short film with some actual war footage.

Sources

[1] Sam K. Cowan, Sergeant York and his People (New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1922), 147. Alvin York, His Own Life Story and War Diary, Tom Skeyhill, ed. (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Doran & Co., 1930), 18, 122. Albert Ross Hogue, History of Fentress County, Tennessee: The Old Home of Mark Twain’s Ancestors (Nashville: Williams Printing Co., 1916), ix-xiv. Eventually, William York built an addition to the cabin separated from the main living area by a breezeway described as a “dogtrot;” see “York’s Early Life,” Tennessee Virtual Archive, and John Perry, Sergeant York (Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 2010), 9.

[2] Cowan, Sergeant York, 105-106.

[3] David D. Lee, Sergeant York: An American Hero (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1985), 4. York, His Own Life Story, 125.

[4] Cowan, Sergeant York, 169-170. York, His Own Life Story, 123-124. The one-room schoolhouse held pupils ages six to twenty.

[5] York, His Own Life Story, 133-134.

[6] Ibid., 132.

[7] Ibid., 141-145. Lee, Sergeant York: An American Hero, 8-10. It has been reported that the untimely death of York’s friend, Everett Delk, was one of his prime reasons for changing his life in 1917. However, author Tom Skeyhill, who interviewed York in 1927 for his book, His Own Life Story and War Diary, stated, “…and that was when he [York] learned that I had interviewed Everett Delk, his pal of “hog-wild days” to which Alvin responded, “Everett must’ve told you God plenty.” (York, 33) After he changed his ways and joined the church, York mentions that Everett or Marion would tempt him to join them for parties but he would refuse (York, 146.) On Find a Grave, there is a record of an Elijah Everett Delk from Fentress County, 1894-1928.

[8] Mark Sidwell, “The Churches of Christ in Christian Union: A Fundamentalism File Research Report,” Bob Jones University Mack Library, (Feb. 16, 2004): 1-3.

[9] York, His Own Life Story, 149-150.

[10] Ibid., 156-163.

[11] York erroneously referred to Major Buxton’s first name as George, an understandable assumption since Buxton always used the initial G. See Ned Buxton, “Sergeant York’s Major,” No Greater Calling, July 13, 2006.

[12] “Conscience Plus Red Hair Are Bad for Germans.” Literary Digest 61, no. 11 (June 14, 1919): 46. George Pattullo, “The Second Elder Gives Battle,” Saturday Evening Post 191, no. 43 (April 26, 1919): 3. York, His Own Life Story, 172-176.

[13] Cowan, Sergeant York, 242.

[14] York, His Own Life Story, 194, 230. Official History of 82nd Division of American Expeditionary Forces 1917-1919, G. Edward Buxton, Jr., ed. (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill Co., 1919), 3, 11. Center of Military History, United States Army in the World War 1917-1919: Training and Use of American Units With the British and French Volume 3 (Washington D.C.: Gov’t Printing Office, 1989 Reprint), pg. 51, para 1a,b,e. Leo P. Hirrel, Supporting the Doughboys: U.S. Army Logistics and Personnel During WW I (Fort Leavenworth: Combat Studies Institute Press, 2017), 21. “Weapons of the Western Front: Rifles,” National Army Museum (UK), accessed April 1, 2019. Bruce Canfield, “The U.S. Model of 1917 Rifle, American Rifleman, July 19, 2018. The U.S. was so unprepared for war that drill training at Camp Gordon began with wooden guns (Buxton 3, 226. Hirrel 21).

[15] Buxton, Official History of 82nd Division, 12.

[16] York, His Own Life Story, 201.

[17] Ibid., 209.

[18] Scott Candler, History Three Hundred Twenty-Eighth Infantry, Eighty-Second Division, American Expeditionary Forces, United States Army, (Atlanta: Foote & Davies Co., 1920), 43-65.

[19] Ibid., 217-220. Buxton, Official History of 82nd Division, 51-59.

[20] York, His Own Life Story, 224. Lee, Sergeant York: An American Hero, 31-33.

[21] York, His Own Life Story: 246, 256, 264.

[22] Lee, Sergeant York: An American Hero, 36.

[23] York, His Own Life Story, 229-231.

[24] Michael E. Birdwell, Celluloid Soldiers: The Warner Bros. Campaign Against Nazism 1934-1941 (NY: NYU Press, 1999), 107-110.

[25] Benedict Crowell, America’s Munitions 1917-1918: Report of Benedict Crowell, the Assistant Secretary of War, Director of Munitions (Washington D.C.: Govt. Printing Office, 1919) 183.

[26] Buxton, Official History of 82nd Division, 3.

Putting the Flint in Flintlocks