Author: Grumpy

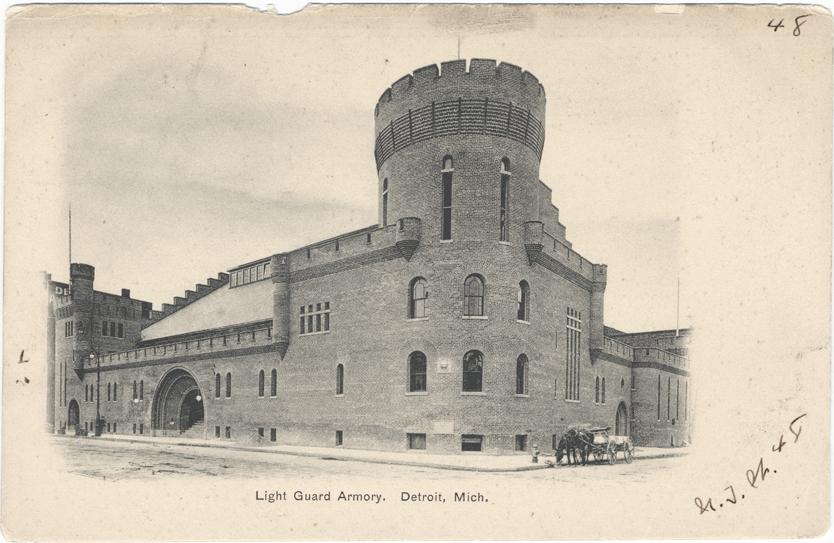

The 1225th Support Battalion has served the city of Detroit since before Michigan was a state. Formed in 1830-1 as the Detroit City Guard, the unit was called into Federal service for the first time in May 1832 for the Blackhawk War under Captain Isaac Rowland. On April 13th, 1836 the unit was reorganized into the Brady Guards in honor of General Hugh Brady. Major General Winfield Scott personally thanked the Guard for mobilizing twice during the Patriot War along the Canadian frontier in 1838-9.

Many members of the company, including future Civil War General Alpheus Williams, served in the 1st Michigan Volunteers during the Mexican War, but the company itself spent the war on patrol along the Canadian frontier. In 1851, the company merged with the Grayson Guards and in 1855 changed their name to the Detroit Light Guard. The Guard was an active organization, working with many elite Northern militia companies, such as Ellsworth’s Zouaves, in the years leading up to the Civil War.

With the coming of the war, the best members of the Guard stepped forward to form Company A of the 1st Michigan Volunteers (Three Months), who arrived in Washington on May 16th. The citizens cheered the men as the first western regiment to arrive in the capital, and drew the comment from President Lincoln, “Thank God for Michigan.”

At Bull Run, the 1st Michigan played a prominent role on the Union right flank on Henry House Hill and advanced farther than any other Federal regiment during the battle. Days later, the regiment returned to Detroit to reorganize into a three-year regiment, and the Detroit Light Guard officially demobilized.

However, Company A remained the active part of the unit, as many members reenlisted with the 1st Michigan. The regiment served in the 1st Division, 5th Corps through the end of the war. They were on the left of the Federal defenses at Gaines’ Mill and Malvern Hill during the Seven Days Battles outside Richmond.

The 1st Michigan was in the thick of the fighting on August 30th, 1862 at Second Manassas in Porter’s attack on Stonewall Jackson’s position. The fighting in front of the railroad cut was fierce and bloody, particularly due to Longstreet’s artillery that took the attack in the flank.

Half of the regiment fell, and Colonel Roberts, a member of the Detroit Light Guard, was shot through the chest and died shortly after. The unit sat in reserve during the Antietam Campaign but was at the center of the fighting at Fredericksburg in the assault on Marye’s Heights, losing 47 men in the relentless but futile attacks.

At Gettysburg, Lieutenant Colonel William Throop, also of the Guard, took command early in the fighting and led the regiment in their defense of the woods on the west end of the Wheatfield.

The Guard was the first infantry unit to engage Lee’s men at the Wilderness in the Overland Campaign. On May 8th, the regiment left the fighting with only 23 men in the ranks. The 1st played a significant part in the counterattack at Jericho Mill on May 23rd, stemming Wilcox’s breakthrough of the Union lines.

It also fought at Bethesda Church, the opening assaults at Petersburg, and was in reserve at Weldon Railroad in August. In September, at Poplar Grove Church, it stormed two enemy fortifications and part of the lines alone. The 1st fought at Hatcher’s Run, White Oak Road, Five Forks, High Bridge, and Appomattox. They stood in ranks with the rest of their division to receive the surrender of Lee’s infantry on April 12th, 1865.

Following the muster out of the volunteer forces at the end of the war, the Detroit Light Guard reformed from the veterans returned home. This was a low point in the militia of Michigan, and by 1870, it was one of three companies left in the state.

The Guard represented the state at the Centennial celebrations in Philadelphia in 1876 and on May 1st, 1882 adopted the tiger as its mascot, a symbol that Detroit still honors as the mascot of their baseball team. During this period, the company maintained its reputation as both a superbly drilled unit and an elite social club.

With the outbreak of war in 1898, three of the Guard’s four companies became part of the 31st Michigan Infantry and shipped out for training camp at the Chickamauga battlefield on May 16th. The 31st Michigan performed garrison duty in Cuba following the Spanish surrender of the island until mustering out in May 1899. The remaining company served with the 32nd Michigan Infantry, which never deployed out of the United States during the conflict.

In 1916, the Guard was mobilized and with the United States’ entry into the First World War in 1917, it was consolidated with the 3rd Regiment of Michigan Militia to form the 125th United States Infantry in the 32nd Infantry Division.

The division reached France in February 1918 and went into training. Its first combat was in the counterattacks during the Second Battle of the Marne in July and August, earning the division the nickname “Les Terribles.” It fought in the Oise-Aisne and the Meuse-Argonne Campaigns and then served in the occupation force in Germany.

The Guard was called up with the rest of the division in 1941 but was pulled from the division in 1942 when it changed into a “Triangular” division.

The Guard spent the war on garrison duty in the United States and, following the war, was split off the 125th Infantry. It moved around and served as an infantry unit in various brigades. In 1967, the Guard helped put down the rioting in Detroit.

In 1992, it was converted from an infantry unit to a logistics unit. Under its current designation, the 1225th Support Battalion, the Detroit Light Guard served in Iraq from 2004-5. The Guard broke ground on its armory in 1897 and has used the building as their drill location since that time.

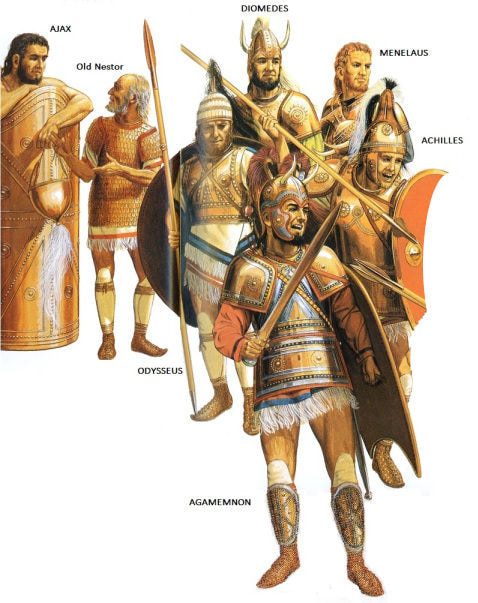

War Art through the ages

&

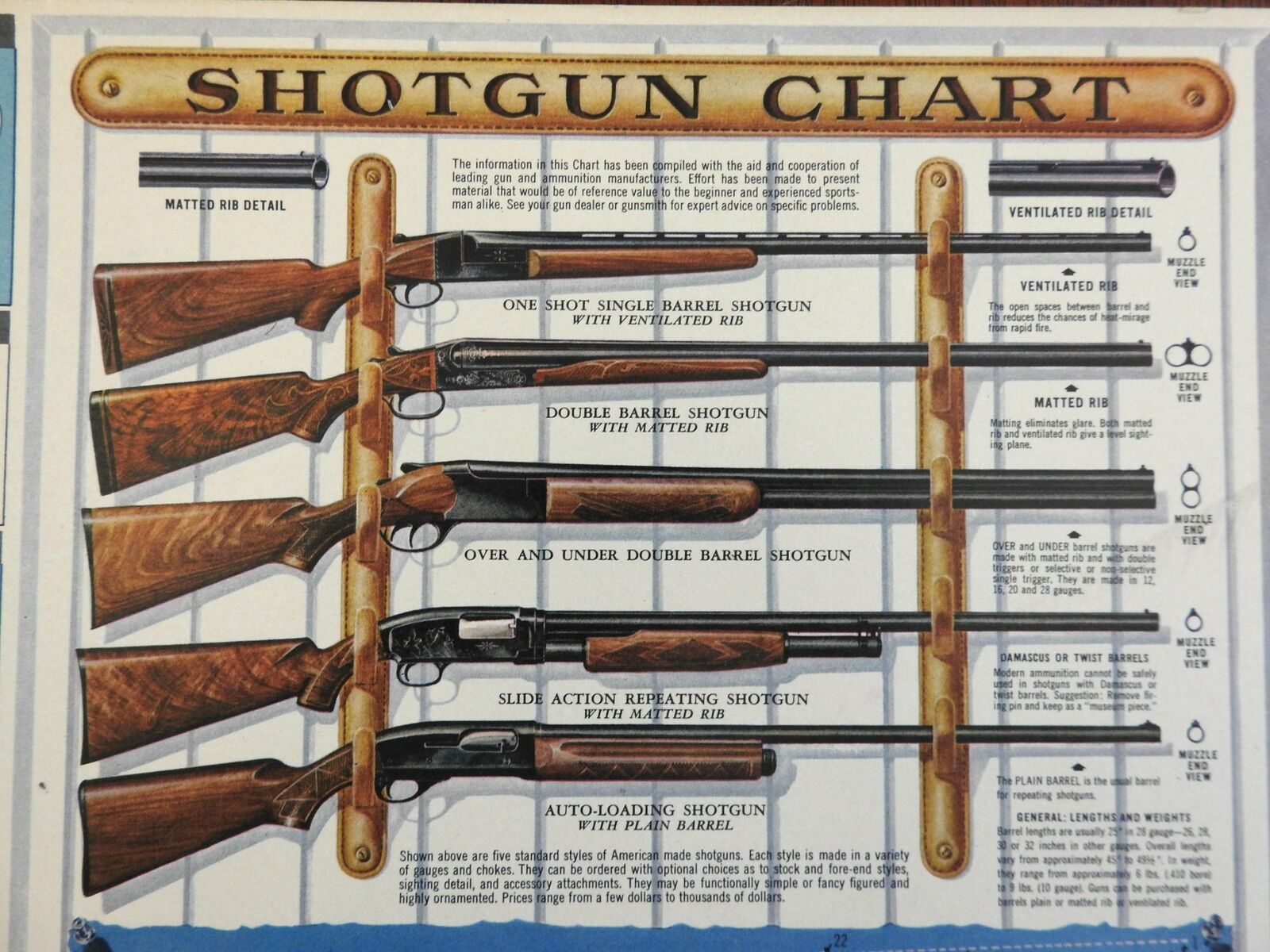

Some Machine Gun Porn perhaps?

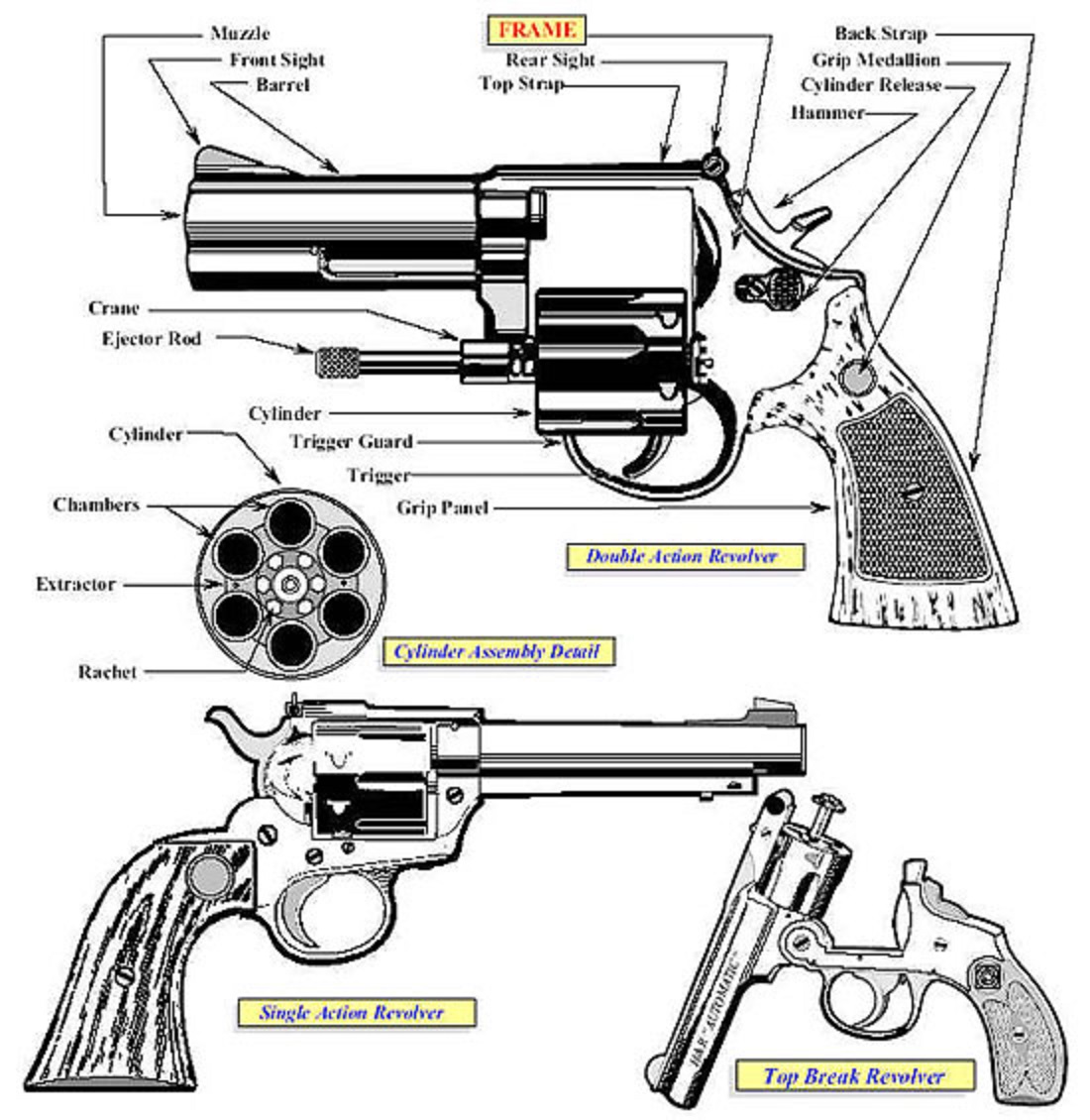

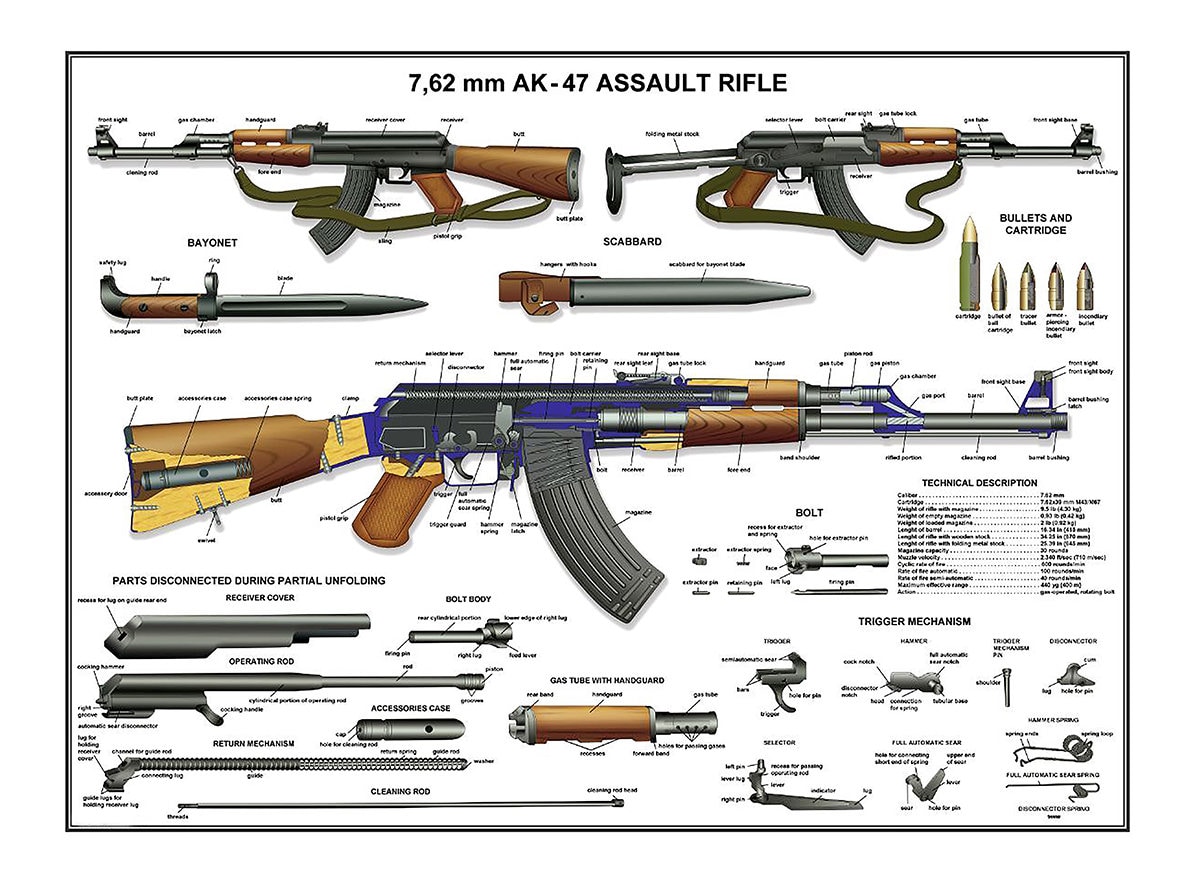

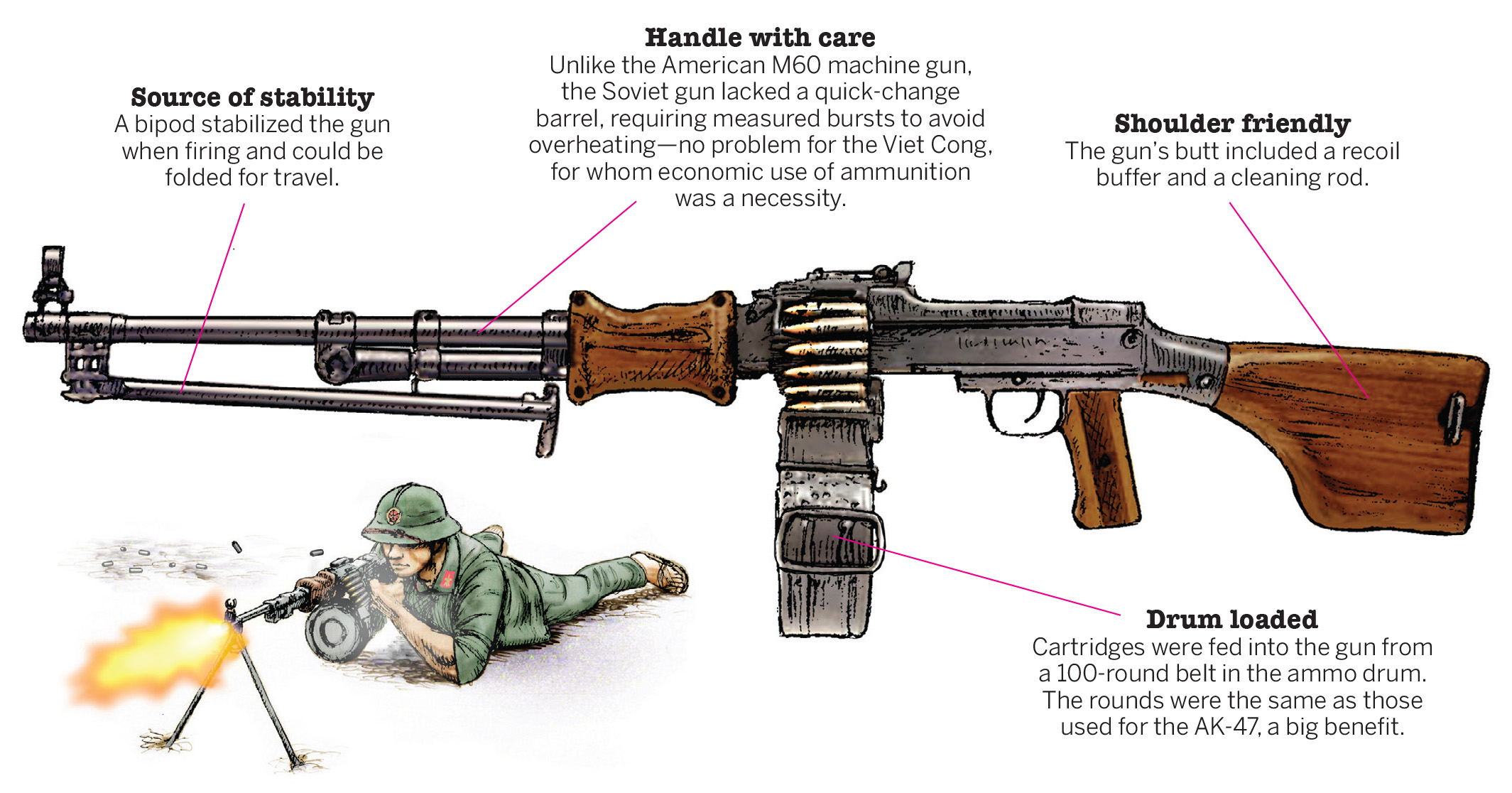

OKAY, OKAY! I just could not help myself on this one or this one! Grumpy

OKAY, OKAY! I just could not help myself on this one or this one! Grumpy

If all you know about pirates comes from watching Disney’s many Pirates of the Caribbean movies featuring Johnny Depp as Captain Jack Sparrow and his crew of the Black Pearl, well, step aboard, Matey; let me tell you the true story of America’s pirates. Arrrgh…much of what you think you know just t’weren’t so!

The Golden Age of Piracy in the Atlantic existed from roughly the 1650s to the late 1720s, with the decade from 1716 to 1726 being the period when most pirates were plying their nefarious trade off America’s eastern seaboard. And, surprisingly, most if not all of the original 13 colonies knowingly welcomed pirates, at least for a time, some even harboring them. Pirate ships brought sorely needed trade goods to the fledgling settlements.

Pirates obtained their ships in true pirate fashion, by stealing them. It usually began when a small merchant or navy vessel—often with an obnoxious, dictatorial captain—experienced a mutiny. The captain and crew members who did not wish to join the mutineers in a life of crime would be put adrift in a small boat or dropped off on a remote island. The mutineers would then turn to capturing ships one by one, robbing them of anything of value: cargo, sails, rigging and the most coveted rewards of all, shipments of gold, silver, coins or precious gems.

The captured ships were referred to as “prizes,” and if a ship was larger or in other ways more desirable than the one the pirates currently had they would simply keep the new one and scuttle or torch the old one. Sometimes they would retain both ships, with a few pirate captains gradually building an armada of half a dozen ships or more. But most pirates didn’t live that long; their brief careers, motivated by greed, often ended in an unexpected, violent death.

Pirate crews, usually about 75 to 80 sailors per ship, were made up almost exclusively of men. But there were two noted exceptions, Anne Bonny and Mary Read, who were part of “Calico” Jack Rackham’s pirate crew. Bonny was Rackham’s lover and Read also had a consort on board. The women did more than share a bed with the pirates, however; they also fought alongside them. Piracy was considered a capital offense, and when Rackham and his crew were captured in 1720 most of the pirates were sentenced to death by hanging, including the two women.

As a way of avoiding the hangman’s noose both women “pleaded their bellies,” meaning they claimed they were pregnant. After having this confirmed, the court granted each woman a temporary stay of execution. Read died while in jail of an unspecified illness and Bonny eventually disappears from the historical record, her ultimate end unknown.

As for the ships themselves, it was the age of sail and all types of craft were hijacked on the high seas and converted to pirate ships: schooners, snows, brigantines and on rare occasions even frigates. But the ultimate pirate ship was a sloop. Fast, with a shallow draft, and easy to handle, sloops were capable of sailing the open ocean as well as maneuvering in dangerous shoal waters close to the coasts. In fact, sailing near shallow, treacherous reefs was one of the pirates’ escape tactics. If they were being pursued by a larger vessel, such as a man-of-war, the pirates would steer toward the shallows, hoping the larger ship with a deeper draft would run aground.

“Guns” on a pirate ship referred to the cannons lining its sides (usually 10 to 20) and varied by size, shooting three, six, nine or 12-pound cannonballs, sometimes even heavier. The cannons could also fire an exploding canister filled with iron pellets known as partridge or swan shot. Bar shot, molded into the shape of a modern-day dumbbell, was fired into a ship’s sails and rigging to slow its progress.

Smaller cannons, known as chase guns, were mounted on the bow and stern of pirate ships. When in pursuit of a “prize,” a chase gun would be used to fire a shot across the ship’s bow, the universal signal for the ship to stop and surrender. On the other hand, if the pirate ship itself was being chased, the stern gun could be used to fire at its pursuer.

Once a ship was stopped, the pirates quickly lowered small boats and rowed to the pursued ship, swarming over its sides, bristling with weapons in hand—pistols, muskets and cutlasses—while clenching knives between their teeth. The firearms were flintlock muzzleloaders, capable of firing only one shot before needing to be reloaded. But there was often no time to reload, especially if the crew of the boarded vessel decided to fight. It was then the cutlass was brought to bear. A slightly-curved, thick-bladed sword of 20 to 30 inches in length, it could be swung in the tight quarters of a crowded deck with devastating consequences.

Whenever possible, though, pirates preferred not to fight. Rather, they hoped to win the day through intimidation by a show of overwhelming numbers of men and firepower. Which is why when the crew of a boarded vessel chose to resist and was defeated, harsh punishment inevitably followed.

Captains were often singled out and tortured by pirates for two reasons: as an example to the remaining crew, and also so the pirates could quickly discover where the valuables on a ship were hidden. Entire crews could also be slaughtered. The Boston News-Letter reported in 1718 that merchant crews “that have made resistance have been most barbarously butchered, without any quarter given to them, which so intimidates our sailors that they refuse to fight when the pirates attack them.”

It’s no wonder then that when a pirate flag was spotted flying atop a quickly approaching ship knees went weak. A white skull and crossbones on a black background—the Jolly Roger—was the iconic pirate flag, but other images were used, as well. One pirate flag pictured a skeleton holding an hourglass, signifying that time was running out for the pursued vessel.

Today, each September 19th since 2002 is celebrated as International Talk Like a Pirate Day. But to be historically accurate don’t say “arrrgh,” as no real pirate ever likely talked like that. It’s just another Hollywood inaccuracy of pirates and piracy—the truth is much more interesting.

If you’d like to read more about The Golden Age of Piracy, the book Black Flags, Blue Waters: The Epic History of America’s Most Notorious Pirates, by author Eric Jay Dolin is highly recommended.